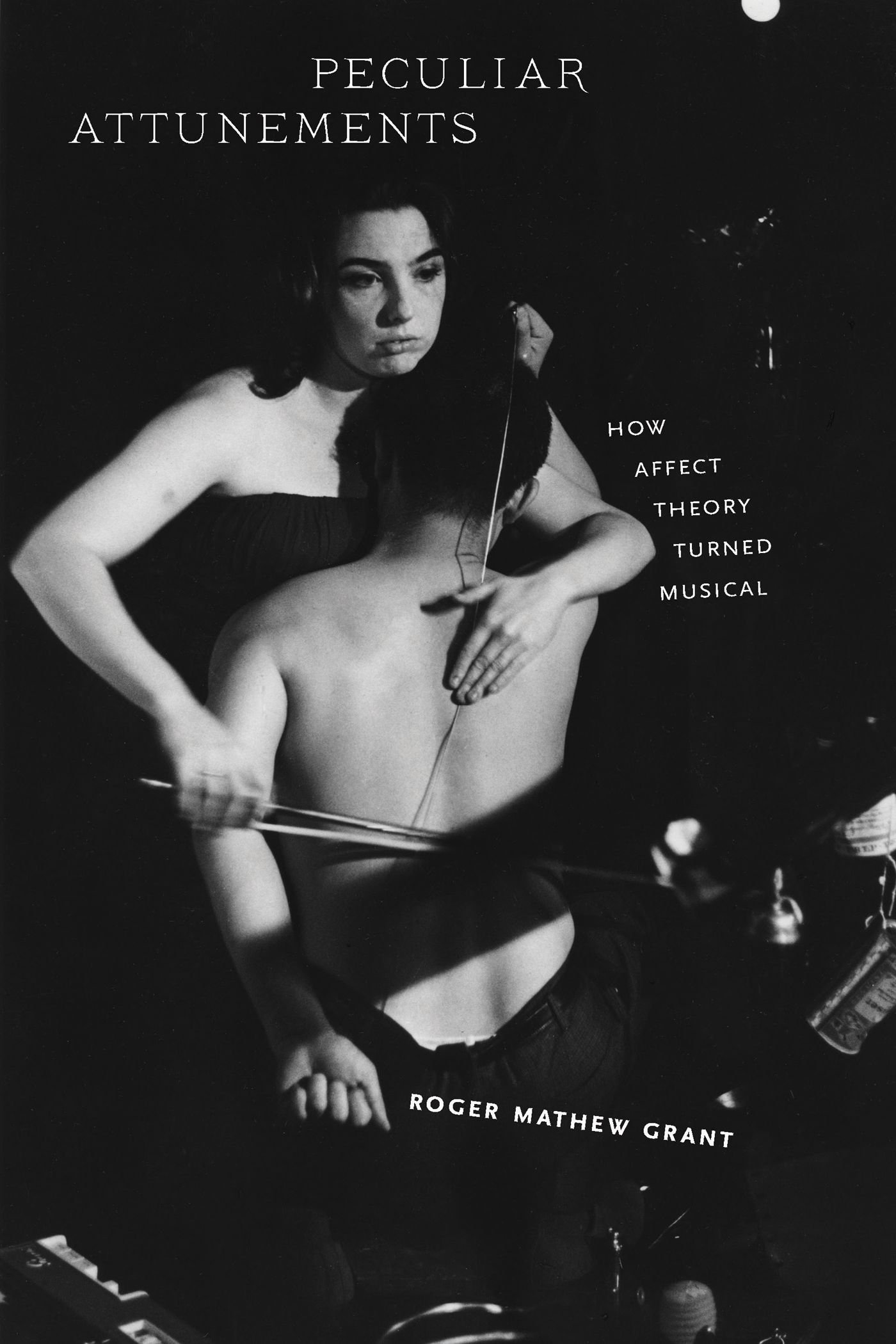

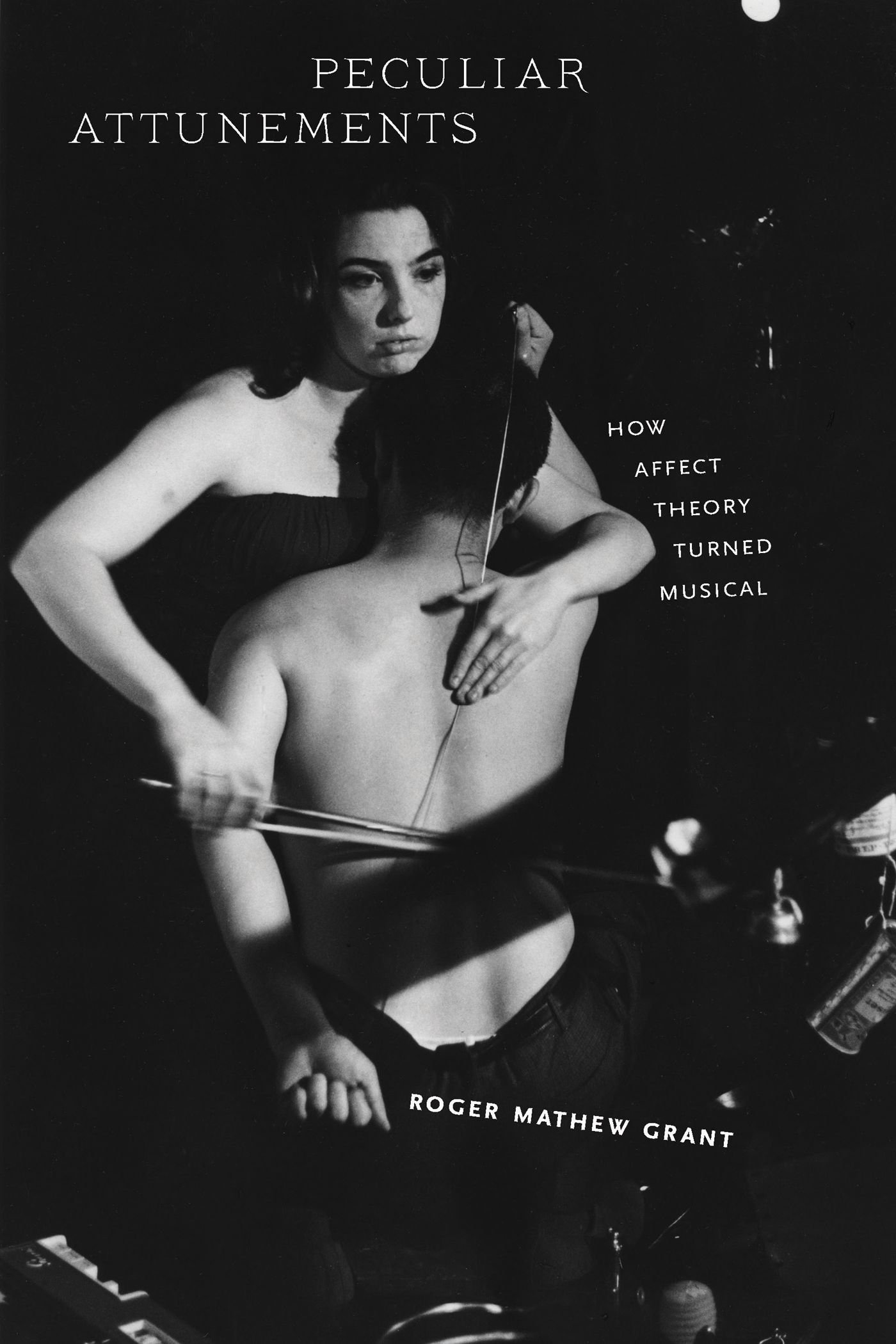

PECULIAR ATTUNEMENTS

| Peculiar

Attunements HOW AFFECT THEORY TURNED MUSICAL |

Roger Mathew Grant

FORDHAM UNIVERSITY PRESSNEW YORK 2020

Copyright 2020 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Visit us online at www.fordhampress.com.

Library of Congress Control Number:2019955796

Printed in the United States of America

22 21 205 4 3 2 1

First edition

Notes on Orthography and Translation

Quotations preserve the spelling and idiosyncrasies of the original wherever possible. All translations are my own unless otherwise indicated.

I had not heard any music for a few days, and I was all charged up, glowing and gratified, so that my sense of everything was heightened. I felt every phrase of the music in a physical way, as if I had turned into a little orchestra myself.

ALAN HOLLINGHURST, THE SWIMMING-POOL LIBRARY

Introduction

Introduction

The music begins: Beethovens Fifth Symphony. The orchestra roars the opening gestures with unsettling power. Your hands become clammy, and your heartbeat accelerates. Watching the stage with anticipation, you hear the pace of events quicken and the music hasten toward some conclusion that it cannot reach. Your breathing becomes heavy, your cheeks flush, the muscles in your back tighten, and your throat closes. A rush of pleasure washes over you.

Affect gives name to the dynamic transformation that is achieved in experiences like these. Contemporary theorists describe affect as corporeal, immediate, and nondiscursive.and social scientists, and whether the apex of this new popularity has already passed or is yet to come, it is safe to say that affect has not always attracted the attention it does today. As the story typically goes, critics have recently favored affect theory in their search for alternatives to the focus on discourse that characterized the linguistic turn. But this narrative is not exclusive to the twenty-first century; it is also the story of a less-well-known movement in intellectual history that occurred in the middle decades of the eighteenth, when European debates on music created a fundamental transformation within aesthetic theory. This is the story of how affect theory turned musical.

Inflecting our current intellectual moment through eighteenth-century music theory and aesthetics, this book reveals formal aspects of historical and contemporary theories of affect. It sets forth a way of thinking through affect dialectically, drawing attention to patterns and problems in affect theory that we have been given to repeating. Finally, it argues for renewed attention to the objects that generate affects in subjects.

Affect has a long and rich intellectual heritage, and the locations of subject and object within it have been anything but uniform. In early modernity, the affectsor the passions, as they were also calledwere important components of an elaborate semiotic system that explained the impact of aesthetic objects. Today, by stark contrast, affect is often explicitly opposed to theories of the sign and of representation; theorists construe affect as a matter of subjective reception that is fundamentally objectless or nonintentional, occasionally even contrasting affect with ideology.

Comparing two pivotal moments within affect theorys history, this book offers a reassessment of affects common systems, processes, and dilemmas. It also aims to draw affect theory into conversation with another, equally vexed archive: the history of music theory. Affective experience and musical sound have created similar problems for theorists. Both are said to act on the body in a material fashion that can be explained with a certain degree of specificity, and yet both are also said to produce transformations within us that exceed and overspill linguistic or rational containment. Music theory and affect theory may yet have much to teach each other.

Music scholars have not completely neglected the early modern turn to affect within music theory; it used to be called the Affektenlehre, or the doctrine of affections.some preliminaries on the intellectual context out of which that earlier turn to affect emerged.

Affect, Representation, Music

Contemporary affect theorists rely on a variety of sources from the history of philosophy, but by far the most important of these is the work of Baruch Spinoza. In the Ethics, Spinoza describes affect [affectus] as the bodys capacity to respond to the world in a preconscious manner that either increases or decreases its power of activity. His theory is particularly attractive to contemporary scholars because it postulates a mind-body union. Not often discussed are the commonalities between Spinozas thought and the work of his important predecessor Ren Descartes. Despite the fact that these two thinkers conceptualized the mind-body relationship in radically different ways, Spinoza and Descartes authored remarkably similar theories of the affects. In addition to nearly identical lists of the basic affects, these thinkers also shared an important commitment to theorize the relationship between the affecting object and the affected subject. Both Spinoza and Descartes endeavored to describe the objects that create affective responses in subjects, especially when these things were reproductions or images of other affect-inducing objects.

For Spinoza, an object that creates an affective response of pleasure or pain in a subject could be anything that causes an increase or decrease in the bodys power of acting. When you see an object that you love, your bodys power of acting is increased, and you experience pleasure. Spinoza specifies that these objects themselves need not be present in order for us to experience an affective response. From the mere fact that we imagine a thing to have something similar to an object that is wont to affect the mind with pleasure or pain, we shall love it or hate it, although the point of similarity is not the efficient cause of these emotions. For Spinoza, mimetically reproduced images of affecting objects have the ability to produce affects in the subject.

Descartes had gone even further to specify the nature of these affective transactions in Les passions de lme of 1649. When we read of unusual adventures in a book or see them represented on a stage, this sometimes excites Sadness in us, sometimes Joy or Love or Hatred.immediate affective response from the subsequent pleasure we take in feeling it, providing the basis for a theory of art.

Eighteenth-century aesthetic theory built on the seventeenth centurys theories of the affects, further elaborating the work of Spinoza, Descartes, and their contemporaries. Affect, in this doctrine, played an important role in systems of signification and representation, fulfilling a function that might seem completely foreign to contemporary affect theory. In eighteenth-century aesthetic theory, representation referred not only to artistic renderings of objects and events but also to the mechanism by which the soul came to know the objects in the world. Representation named what was then an unknowable connection between the soul and the sensorium; according to certain models, the soul was completely constituted by representation.that construed affect as an essential component in the experience of artone they endeavored to describe and explain.

Next page

Introduction

Introduction