Edward Chancellor

THE PRICE OF TIME

The Real Story of Interest

Atlantic Monthly Press

New York

Copyright 2022 by Edward Chancellor

Jacket design by David Plunkert

Jacket artwork: The Money Changer and his Wife, 1514, Quentin Metsys.

Muse du Louvre, Paris agefotostock/Alamy

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by Allen Lane, An imprint of Penguin Random House UK

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

First Grove Atlantic hardcover editon: August 2022

Typeset in the UK by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-6006-5

eISBN 978-0-8021-6007-2

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

For Henry Maxey

A reward for waiting.

Nothing is more amusing than the multitude of laws and canons made in every age on the subject of the interest of money, always by wiseacres who were hardly acquainted with Trade and always without effect.

Richard Cantillon, 1730

The question of interest has long been the object of contemptuous neglect.

Eugen von Bhm-Bawerk, 1884

Dont give me a low rate. Give me a true rate, and then I shall know how to keep my house in order.

Hjalmar Schacht, Reichsbank president, 1927

Our earth is degenerate in these latter days: bribery and corruption are common; children no longer obey their parents; every man wants to write a book, and the end of the world is evidently approaching.

Assyrian tablet, c. 2,800 BC

List of Illustrations

Code of Hammurabi, 1750 BC . (Photograph: Science History Images / Alamy)

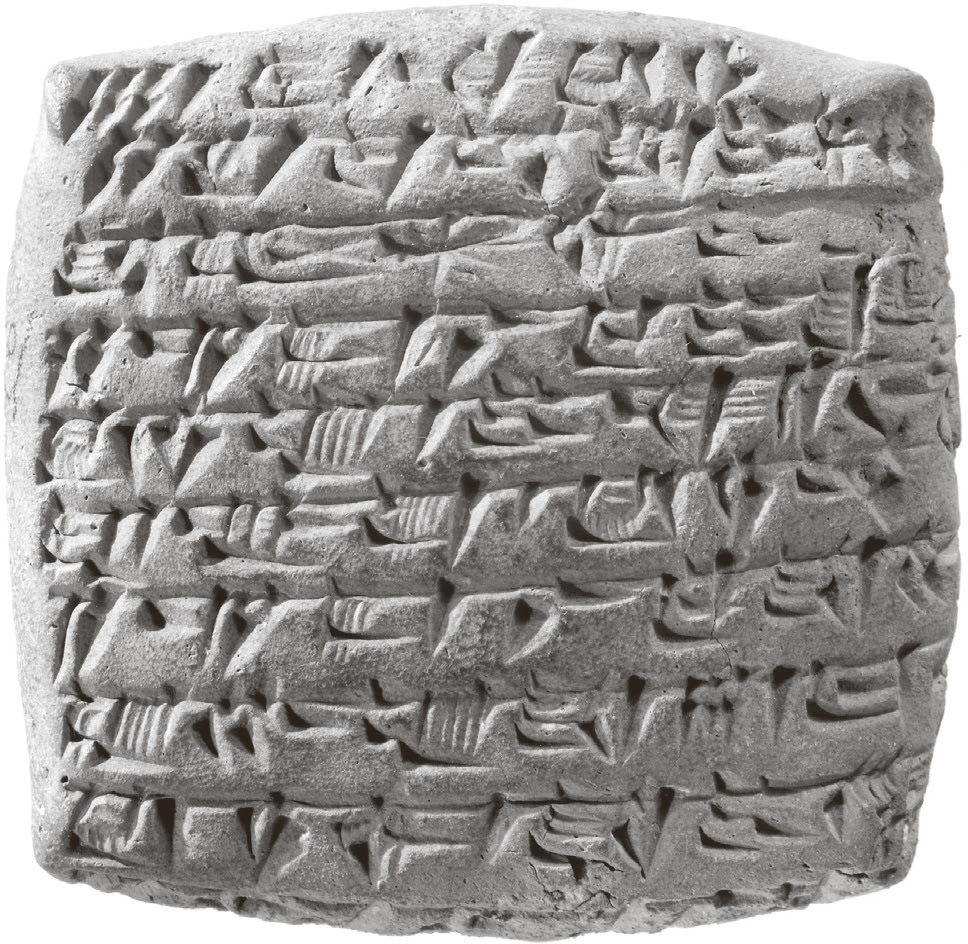

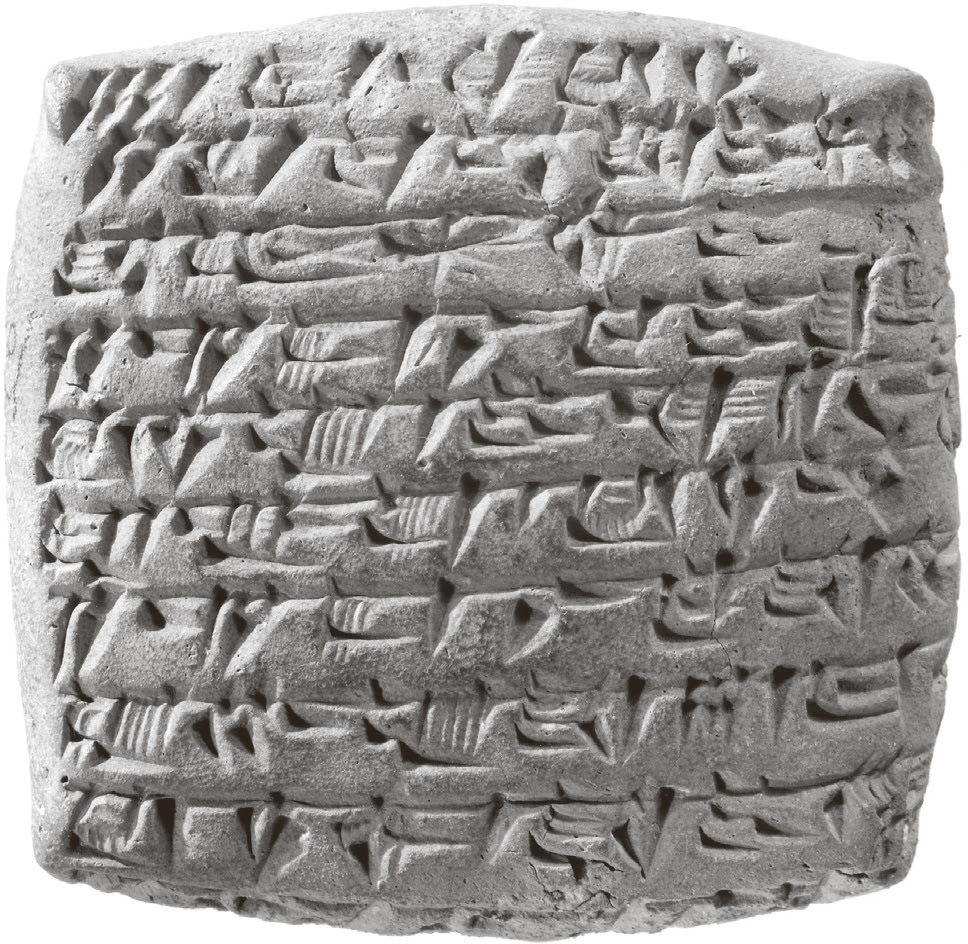

Cuneiform tablet: quittance for a loan in silver, c. 20th19th century BC . (Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mr and Mrs J. J. Klejman, 1966. Photograph: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

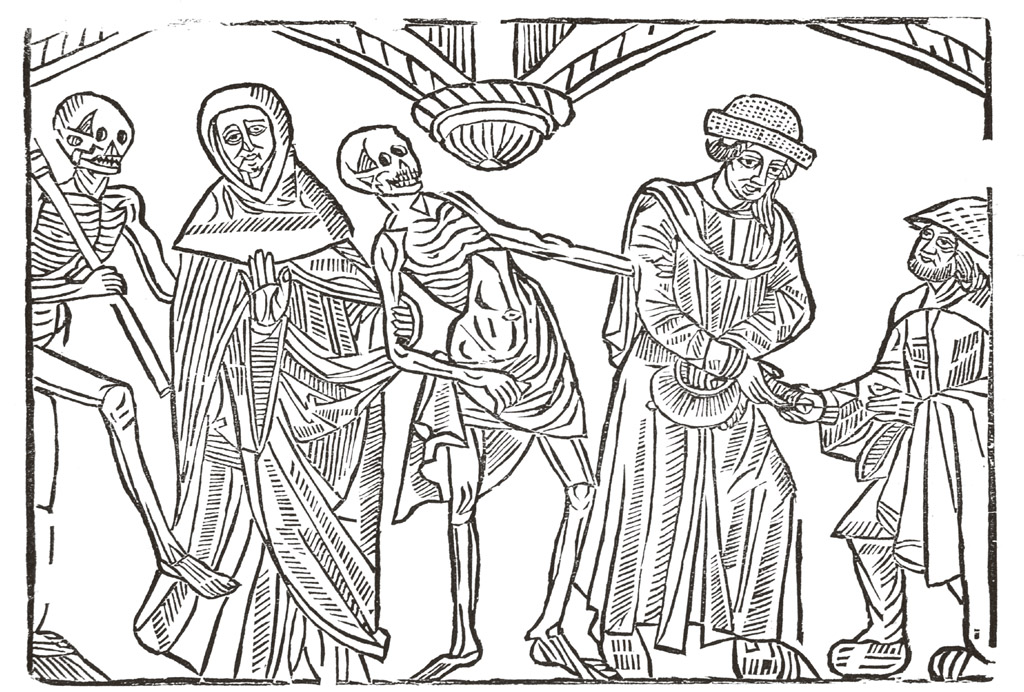

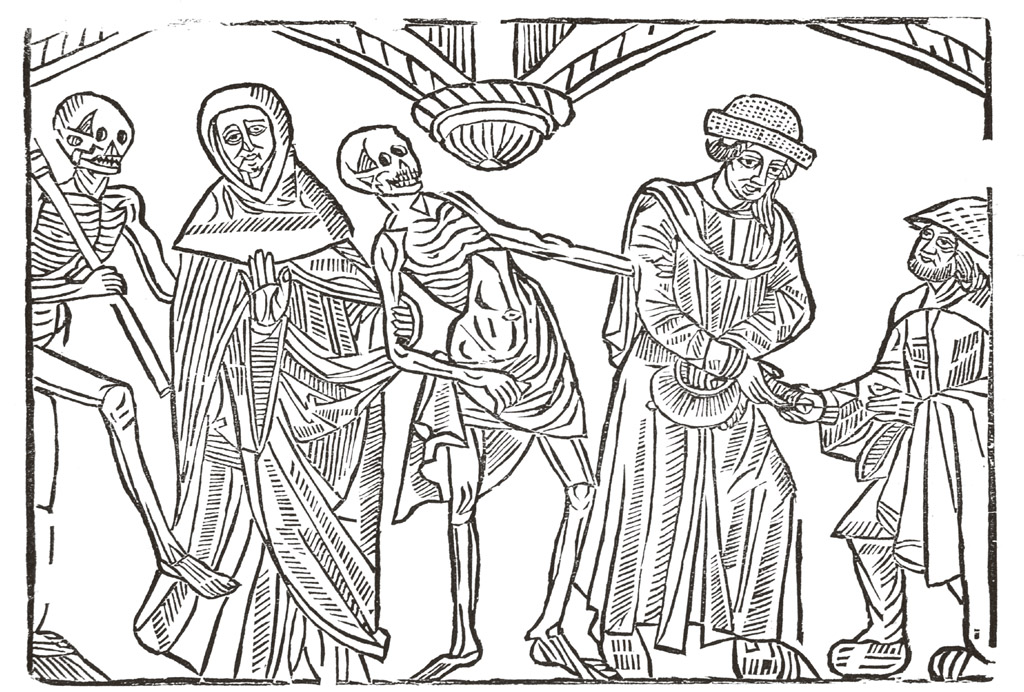

Death of a monk and a usurer (litho), French school. (Photograph: The Stapleton Collection / Bridgeman)

The Money Lender and his Wife, 1514 (oil on panel) by Quentin Massys (c. 14661530). (Photograph: Bridgeman)

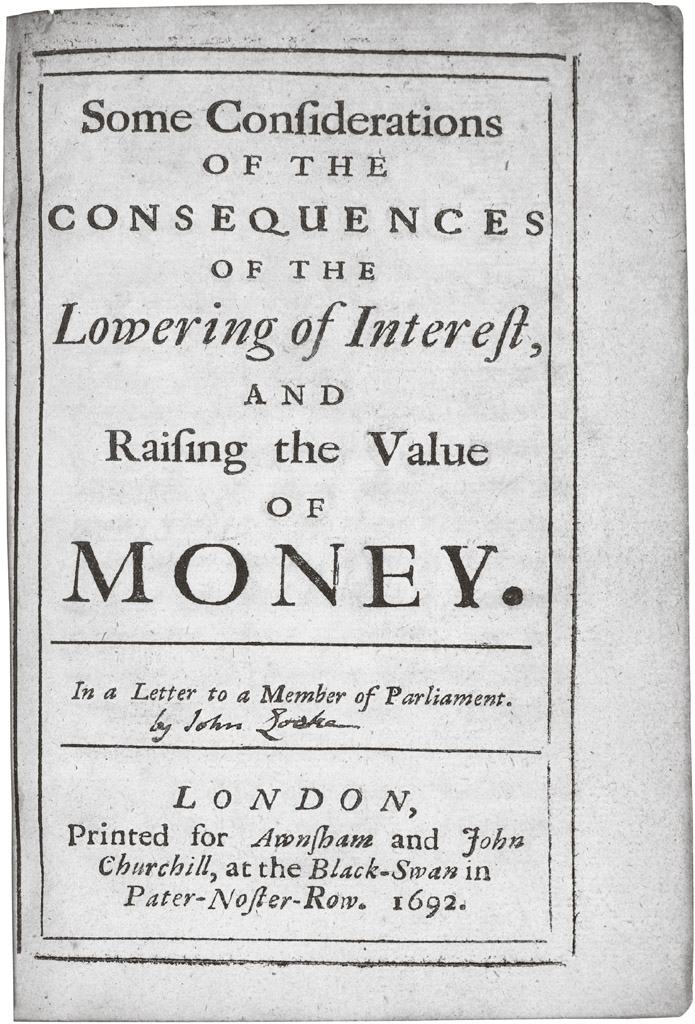

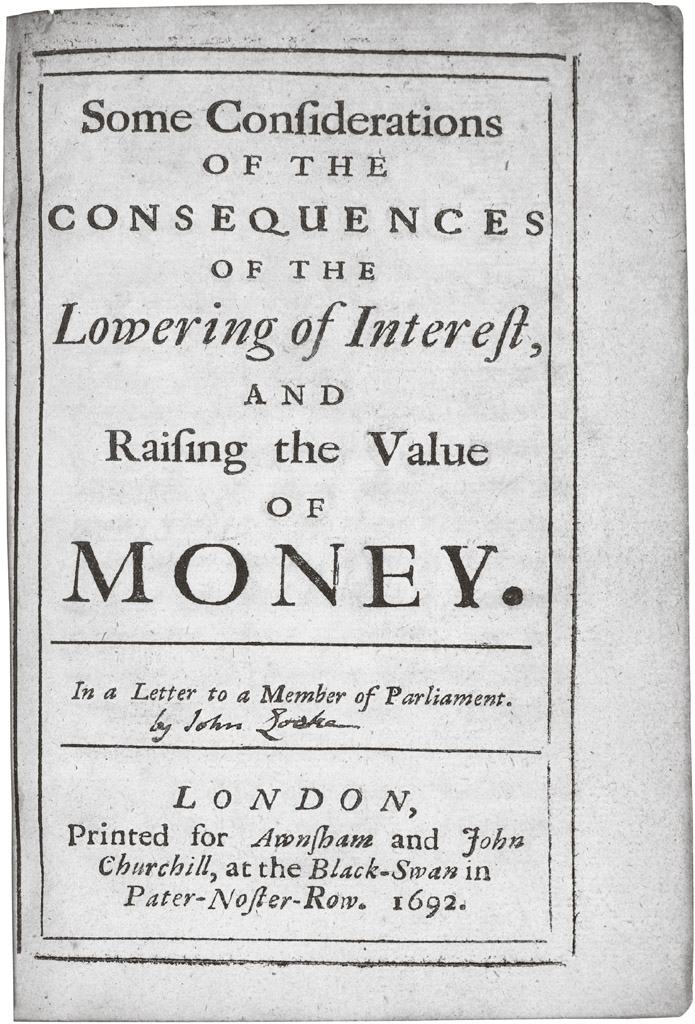

Some Considerations of the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money, by John Locke, 1691. (Photograph: copyright Christies Images / Bridgeman)

Portrait of John Law by Leonard Schenk, 1720. (Photograph: Rijksmuseum)

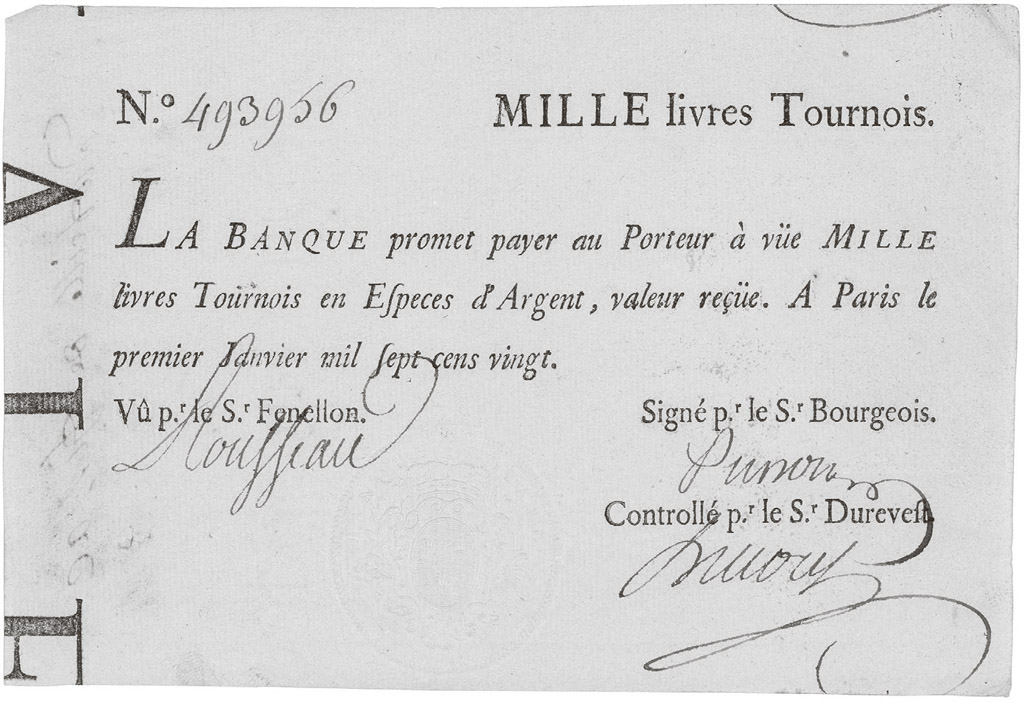

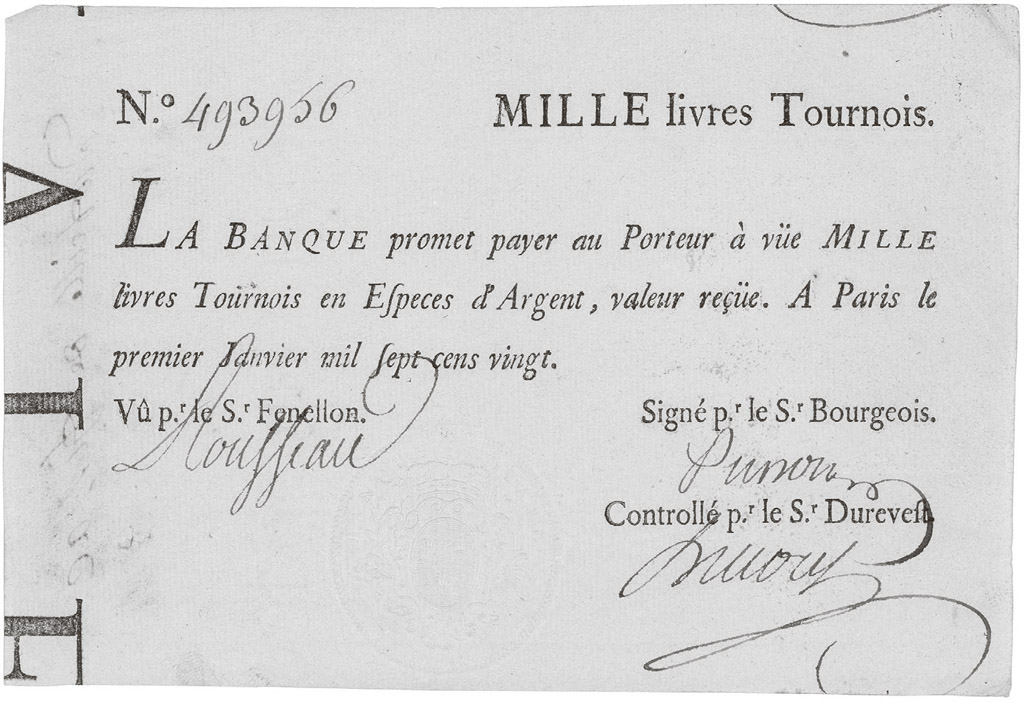

A banknote of John Laws Banque Royale, Paris, 1 January 1720. (Photograph: copyright Christies Images / Bridgeman)

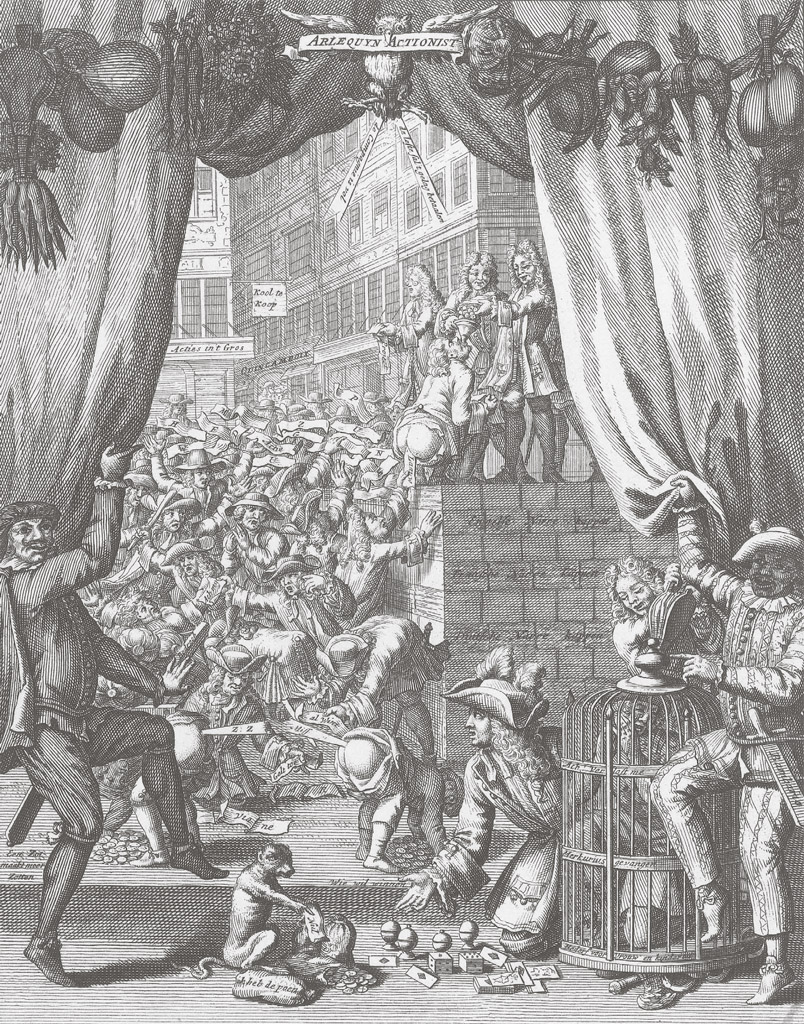

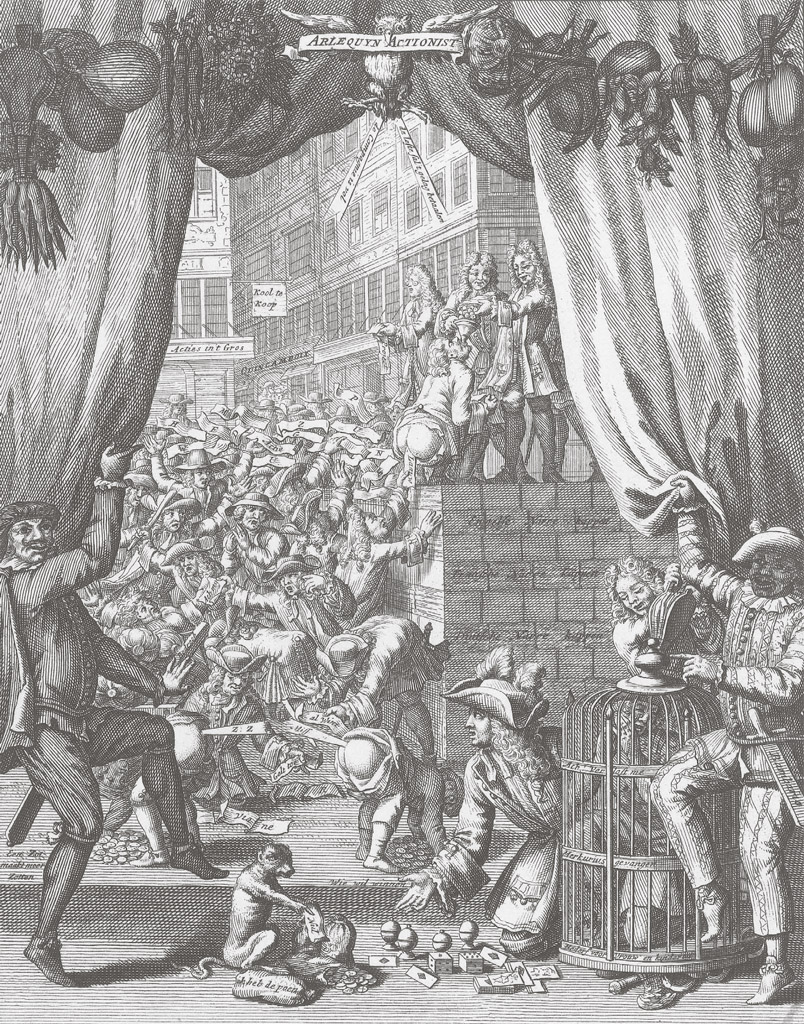

Satirical illustration of speculators in the rue Quincampoix during the Mississippi Bubble, Het Groote Tafereel der Dwaasheid, 1720. (Photograph: Rijksmuseum)

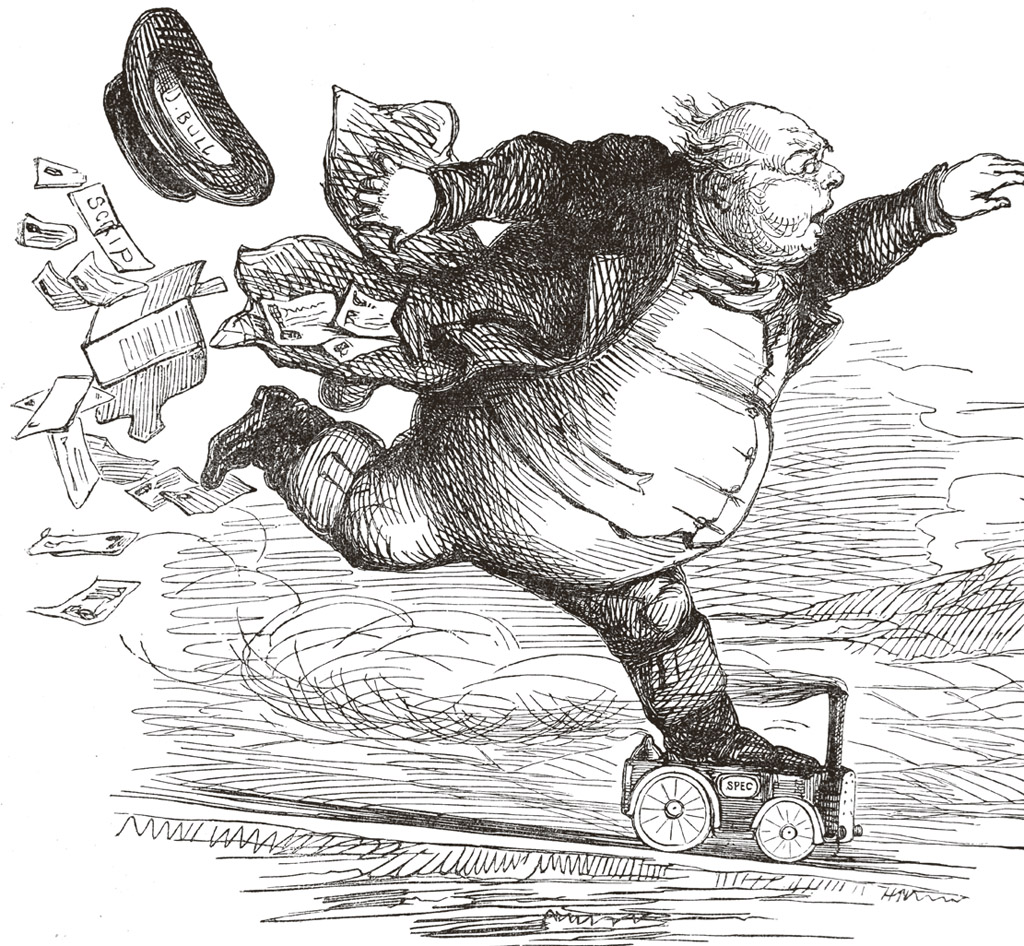

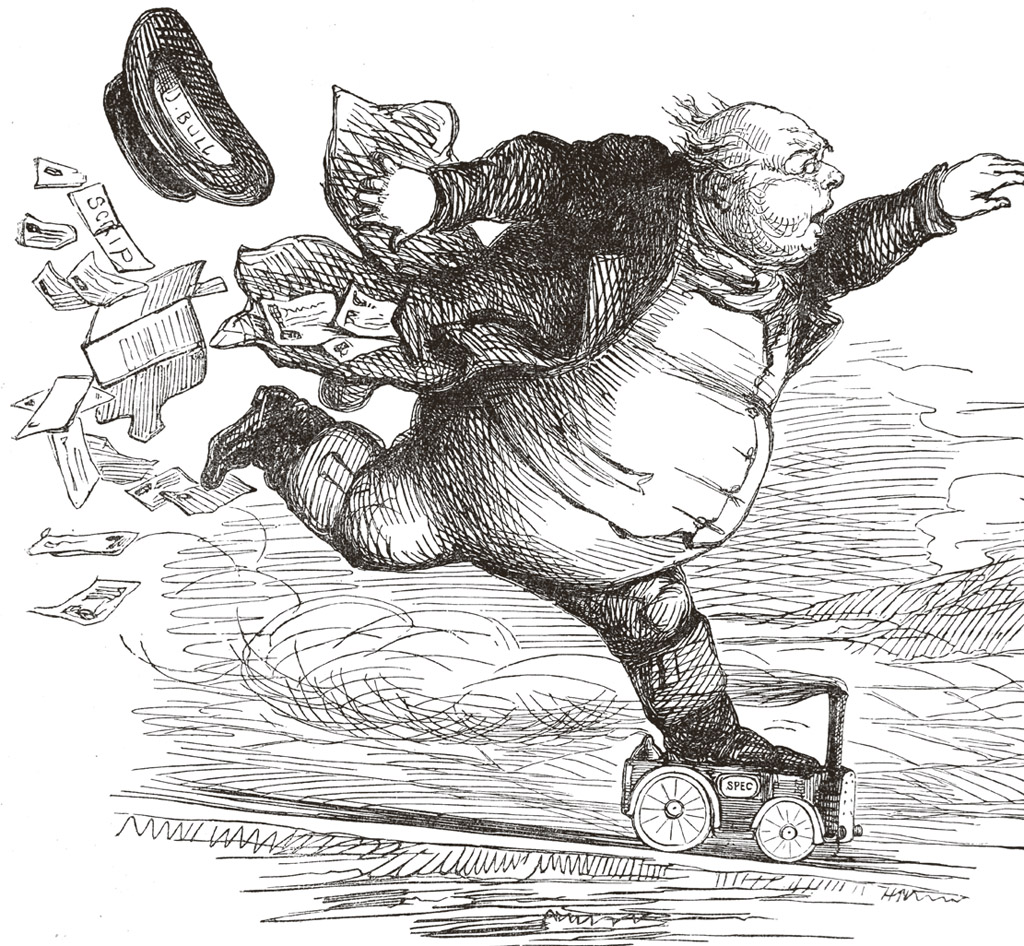

Cartoon depicting John Bull balanced atop a steam engine, nineteenth century. (Photograph: World History Archive / Alamy)

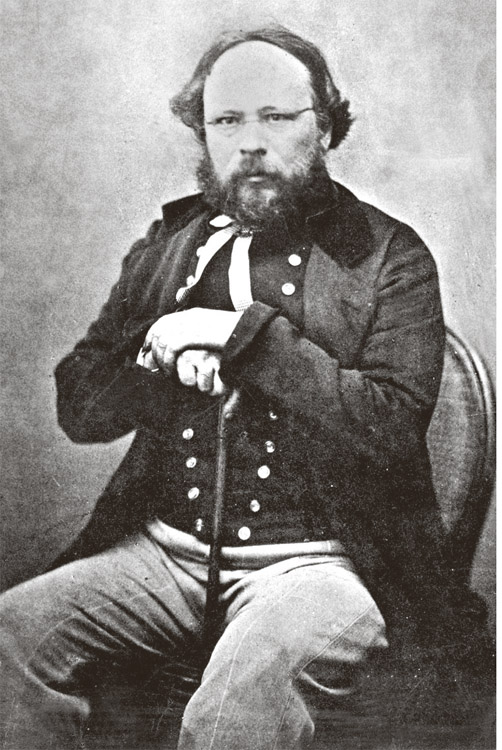

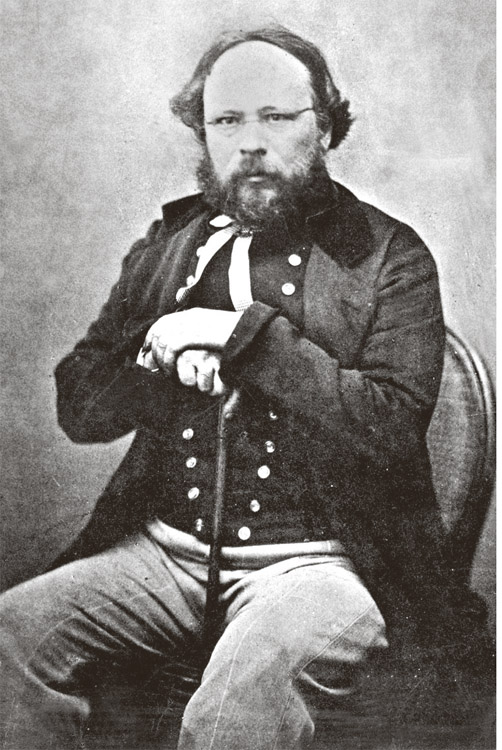

Pierre Joseph Proudhon (18091865), French socialist and political theorist. (Photograph: Bridgeman)

Portrait of Frdric Bastiat, French economist (180150) by an unknown artist, nineteenth century. (Photograph Stefano Bianchetti / Bridgeman)

The Overstone Cycle of Trade (from a print). (Photograph: Senate House Library, University of London)

Portrait of central bankers Hjalmar Schacht, Benjamin Strong and Montagu Norman, c. July 1927. (Photograph: Federal Reserve Bank of New York)

Christies auction of Salvator Mundi, a painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, 15 November 2017. (Photograph: Eduardo Munoz Alvarez / Getty)

This basalt stele from

c. 1760 BC depicts the sun god Shamash (seated) handing a body of laws to the Babylonian king, Hammurabi. The cuneiform text below contains regulations limiting the maximum rate of interest and prescribing conditions for loan forgiveness.

By the second millennium BC , Mesopotamian merchants were travelling long distances for trade and financing their activities with interest-bearing loans. This cuneiform tablet from Kltepe in Central Anatolia records the discharge from debt for a silver loan owed to a merchant named Ashur-taklaku.

A woodcut from Guyot Marchants

Danse Macabre (1485) shows a usurer (

second from right) taking money from a poor man while Death tugs on his sleeve.

A tender portrait of an Antwerp moneylender and his wife painted in 1514 by the Flemish artist Quentin Massys reflects the more sympathetic attitude to money-lending that emerged in sixteenth-century Europe.

John Lockes pamphlet was the first attempt to consider the harm done by taking interest rates below their natural level. Locke was opposed by the City of London merchant Sir Josiah Child, who stood to benefit from lower borrowing costs.

John Law established a national bank in France in 1719, which printed paper money to bring down interest rates.

And drive up the value of shares in his Mississippi Company. Laws System, a giant Ponzi scheme, collapsed after inflation took off.

A harlequin and a fool lift the curtains exposing frenzied trading in Mississippi shares in the open-air stock market of Pariss rue Quincampoix. This print appeared in a 1720 satire entitled

The Great Mirror of Folly.

The archetypal Englishman, John Bull, careens atop a steam engine, with railway scrip pouring out of his pockets a satire on Britains Railway Mania of 1845.

This basalt stele from c. 1760 BC depicts the sun god Shamash (seated) handing a body of laws to the Babylonian king, Hammurabi. The cuneiform text below contains regulations limiting the maximum rate of interest and prescribing conditions for loan forgiveness.

This basalt stele from c. 1760 BC depicts the sun god Shamash (seated) handing a body of laws to the Babylonian king, Hammurabi. The cuneiform text below contains regulations limiting the maximum rate of interest and prescribing conditions for loan forgiveness. By the second millennium BC , Mesopotamian merchants were travelling long distances for trade and financing their activities with interest-bearing loans. This cuneiform tablet from Kltepe in Central Anatolia records the discharge from debt for a silver loan owed to a merchant named Ashur-taklaku.

By the second millennium BC , Mesopotamian merchants were travelling long distances for trade and financing their activities with interest-bearing loans. This cuneiform tablet from Kltepe in Central Anatolia records the discharge from debt for a silver loan owed to a merchant named Ashur-taklaku. A woodcut from Guyot Marchants Danse Macabre (1485) shows a usurer (second from right) taking money from a poor man while Death tugs on his sleeve.

A woodcut from Guyot Marchants Danse Macabre (1485) shows a usurer (second from right) taking money from a poor man while Death tugs on his sleeve. A tender portrait of an Antwerp moneylender and his wife painted in 1514 by the Flemish artist Quentin Massys reflects the more sympathetic attitude to money-lending that emerged in sixteenth-century Europe.

A tender portrait of an Antwerp moneylender and his wife painted in 1514 by the Flemish artist Quentin Massys reflects the more sympathetic attitude to money-lending that emerged in sixteenth-century Europe. John Lockes pamphlet was the first attempt to consider the harm done by taking interest rates below their natural level. Locke was opposed by the City of London merchant Sir Josiah Child, who stood to benefit from lower borrowing costs.

John Lockes pamphlet was the first attempt to consider the harm done by taking interest rates below their natural level. Locke was opposed by the City of London merchant Sir Josiah Child, who stood to benefit from lower borrowing costs. John Law established a national bank in France in 1719, which printed paper money to bring down interest rates.

John Law established a national bank in France in 1719, which printed paper money to bring down interest rates. And drive up the value of shares in his Mississippi Company. Laws System, a giant Ponzi scheme, collapsed after inflation took off.

And drive up the value of shares in his Mississippi Company. Laws System, a giant Ponzi scheme, collapsed after inflation took off. A harlequin and a fool lift the curtains exposing frenzied trading in Mississippi shares in the open-air stock market of Pariss rue Quincampoix. This print appeared in a 1720 satire entitled The Great Mirror of Folly.

A harlequin and a fool lift the curtains exposing frenzied trading in Mississippi shares in the open-air stock market of Pariss rue Quincampoix. This print appeared in a 1720 satire entitled The Great Mirror of Folly. The archetypal Englishman, John Bull, careens atop a steam engine, with railway scrip pouring out of his pockets a satire on Britains Railway Mania of 1845.

The archetypal Englishman, John Bull, careens atop a steam engine, with railway scrip pouring out of his pockets a satire on Britains Railway Mania of 1845.