Olympic National Park

As winter snow melts back from High Divide in the central Olympics, fields of avalanche lilies flutter in the summer breeze. The glaciers of Mount Olympus in the background are still laden with winter snow. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

Plants of the alpine and subalpine zones have adapted to cope with quickly changing conditions. An early summer snowfall melts back from the blossoms of spreading phlox. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

Lake Constance and Avalanche Canyon below Mount Constance are carved into thick marine basalts of the Crescent Formation. The rugged character of the east Olympics is a product of its geological origins. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

As soon as snow melts from the high mountains, even rock faces and ridgetops burst into bloom. Spotted saxifrage, arnica, and Davidsons penstemon grow among splintered shale near Gray Wolf Pass. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

Dawn light on Mount Olympus. Collecting more than 100 feet of snowfall each year, Mount Olympus supports the lowest-elevation system of glaciers in the forty-eight contiguous states. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

The crevassed mouth or snout of Blue Glacier on Mount Olympus. Like many large glaciers in the Olympics, Blue Glacier has been in fairly steady retreat since the 1920s. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

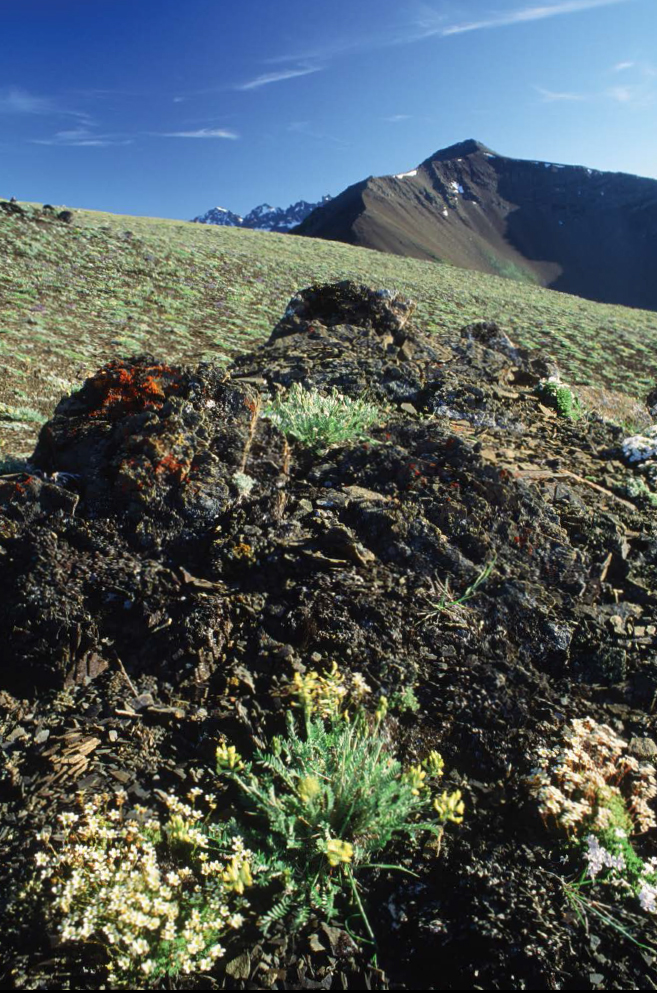

Tufted saxifrage, mountain oxytropis, and spreading phlox are typical of the hardy low-growing plants found in Olympics alpine zone. Summers are short and conditions often severe in this realm above the trees. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

An Olympic endemic, Fletts violet, prefers rocky crevices. Blossoming in early summer, it brings a special delight to alpine scramblers. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

Winter on Gray Wolf Ridge. In the heart of the northeast rainshadow, stunted lodgepole pines reach toward treeline on dry south-facing slopes. An adaptable tree, at home in stressful environments, lodgepoles also thrive in a few locations along the Pacific coast and Puget Sound. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

One of the most beautiful of Olympics endemic plants, Pipers bellflower, grows in cracks and crannies in the rocks of the high mountains. Biologists suspect it is a paleoendemic, a plant whose former range was erased by the Cordilleran ice sheet. Its closest relative grows more than 600 miles to the north. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

Lavender beds of broad-leaved lupine flourish in Olympic high country summers. PHOTO BY STEVEN CASTRO/SHUTTERSTOCK.

Sunset from Blue Mountain. The rounded foothills west of Blue Mountain reflect shaping by the Juan de Fuca lobe of the Vashon ice sheet 16,000 years ago. One lobe of ice flowed west over these low ridges and foothills toward the Pacific, carving the Strait of Juan de Fuca; another pushed south along the east Olympics to carve Puget Sound. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

Lichens color a basalt outcrop on Blue Mountain. The jagged spires of the Needles, in the distance, are part of the Olympics inner basalt ring, a section of submarine lava sheared off by faulting and folded in among mixed sedimentary rocks. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

Coastal fog, essential to the peninsulas famed temperate rain forests, works its way inland, up Olympic valleys, and spills over high ridges. Beneath the cloud layer, moss- and lichen-draped trees sift the fog into a fine rain that falls on shaded forest floors. PHOTO BY MATT WILLIAMS.

Lake Crescent after a rain. As winter clouds rise over the mountains, they bury the high country in snow, but in the lowlands precipitation falls mainly as rain. Lake Crescent, seventeen miles west of Port Angeles, receives more than eighty inches of rain a year. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

Its slightly drooping limbs and short flat needles make western hemlock easy to recognize. Hemlocks tolerance to shade makes it the major understory tree in Olympic forests, and it is common from coastal areas well into the mountains. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

The sight of Roosevelt elk in valley forests always brings a thrill. It was to protect elk habitat that Theodore Roosevelt created Mount Olympus National Monument in 1909. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

East Olympic rivers have a character and flavor all their own. Streams like the Duckabush are marked by narrow valleys and steep gradients. Down logs play an important role in these rivers, regulating high flows and creating pools and hiding cover for young salmon and trout. PHOTO BY KEITH LAZELLE.

The vibrant red

Next page