Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2012 by Thomas Hall

All rights reserved

Front cover: Last Fight of the Speedy, 1804, Peter Rindlisbacher.

First published 2012

e-book edition 2012

ISBN 978.1.61423.625.2

print ISBN 978.1.60949.679.1

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Dedicated to those that go down to the sea in ships

and those that go down to find them.

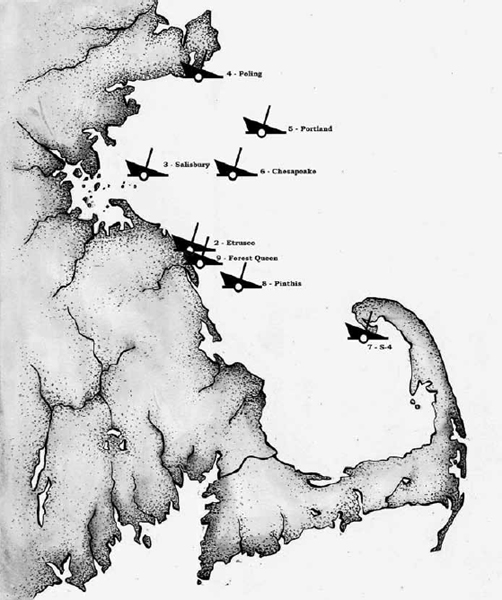

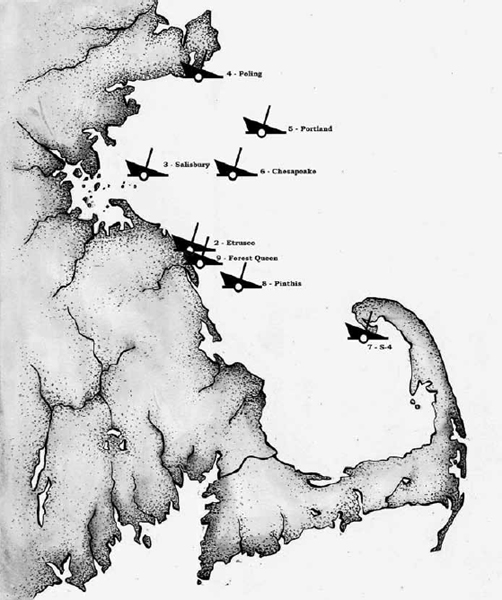

Location of the eight wrecks covered in the book with corresponding chapters.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

There is a granite monument over a mass grave in Wellfleet that reads, In memory of those brave mariners lost in the wreck of the British ship Jason off the back shore of Cape Cod December 5, 1893. The monument lists the names of the twenty-six men lost and one survivor on that fateful day. It was created and funded by the Wellfleet Historical Society as well as several other groups dedicated to the Bicentennial in 1976.

Behind the Congregational Church in Scituate, there is a mass grave marked by a large rock with the inscription In memory of the sailors wrecked on Egypt Beach 1844. Bodies rest here. This wreck is even more obscure than the Jason. In fact, none of the local historians know the names of the boat and crew or the circumstances of its demise. No one in Scituate is related to this unknown wreck filled with sailors lost to history; I suspect no one in Wellfleet is related to those lost on the Jason. Still, in both cases, we are touched enough by the tragedy to build a monument.

These types of monuments dot the coastline of Massachusetts Bay. One of the most famous is in Gloucester and reads, They that go down to the sea in ships (16231923). The inscription is taken from Psalm 107, which reads:

They that go down to the sea in ships,

That do business in great waters;

These see the works of the Lord,

And his wonders in the deep.

Facing out of Gloucester Harbor, the statue shows a helmsman sailing as close hauled to the wind as possible, straining to keep his vessel on course, presumably to clear dangerous rocks. As one of the most active fishing ports in New England over the last four centuries, many families in Gloucester have experienced the pain of losing a relative and friend to the sea. A notable recent example is the Andrea Gail, the fishing boat that went down in 1991 and was the subject of the movie The Perfect Storm.

I discovered my favorite monument to a mariners fate when I was researching my first book The T.W. Lawson: The Fate of the Worlds Only Seven-Masted Schooner. On St. Agnes in the Isles of Scilly, southwest England, there is a church with a stained-glass window that reads, In memory of all those from St. Agnes who put to sea to save the lives of others. Behind this small church there are a number of graves of sailors lost in wrecks and sailors lost trying to save them. There is a mass grave containing those that perished when the T.W. Lawson went down, including Billie Cook Hicks, the Trinity House pilot who went aboard the T.W. Lawson to get her to safety.

What is it about shipwrecks and the sea that fascinates us? Or reading Edgar Allen Poe and Mary Shelley and going to horror movies? Is it that there is not much that separates a gentle sail along the coast with a terrifying noreaster blowing us toward the rocks? Wrecks make us wonder if we have what it takes to navigate out of a storm. Are we good enough? Can our boat handle it? Does it matter? When a storm kicks up with huge waves and strong winds or a dense fog blankets a busy channel, is there anything we can do but experience the same brutal and terrifying fate as those before us? Is the psychology that forces us to look at a wreck along the highway and gazelles to watch their own get eaten by a lion the same that moves us to study and dive on shipwrecks?

Psychologists like Carl Jung have studied this question and concluded that if we approach darkness and the macabre in the right way, it can lead to light. Jung would say we find disasters titillating, a weird physiological arousal and an animal stimulationwith evolutionary value. In the case of the gazelles, she watches her fawn getting eaten by a lion and learns what not to do. And some humans might share this traitwhen we see or study a wreck and the people onboard, we learn what not to do. But we get more: we get to know ourselves better.

According to Jung, morbid curiosity causes us to think about the meaning of suffering, death and life. Our curiosity with shipwrecks causes us to think about the suffering, death, fear and destruction an angry sea can bring to mariners and their families. But there are other reasons we are fascinated by wrecks. This fascination can be lucrative, as these fateful ships often contain valuable cargo from gold and silver to Chinese porcelain and timber. The pursuit of knowledge and artifacts well below the surface is also adventurous, exciting and fun. So we wonder about those that go down to the sea in ships and fail to return; we build monuments to their fate and are fascinated by what lies below the surface.

Mass Bay showing Stellwagen Bank. Courtesy NOAA.

Held by a distinctive arm along the coast of Massachusetts and extending as far as thirty miles out to sea, Mass Bay covers over eight hundred square miles, making it one of the largest bays in the Atlantic Ocean. The mouth of Mass Bay is guarded in the east by Stellwagen Bank, an underwater plateau stretching nineteen miles from the tip of Cape Cod north and six miles across at its widest point. The bay is enclosed in the west by Boston and its South and North Shores, in the north by Cape Ann and in the south by Cape Cod and includes Boston Harbor, Dorchester Bay, Quincy Bay, Hingham Bay and Cape Cod Bay. This prevalence of bays in Massachusetts, especially when you include the adjacent Narragansett and Buzzards Bays, gives the commonwealth the nickname The Bay State. It is part of the Gulf of Maine, which reaches from Cape Cod to Nova Scotia. As we will see time and time again, ships entering Mass Bay in a noreaster are soon trapped deep inside its labyrinth, embraced by the arm of Cape Cod and neck of Cape Ann and pushed onto the rocky lee shores by the wind and waves.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Ice Age glaciers began retreating from eastern Massachusetts around eighteen thousand years ago, leaving portions of Stellwagen Bank dry and home to grasses, forests and animals. It is likely around twelve thousand years ago that Native Americans inhabited these areas and exploited the rich marine resources found along the shore. Rising sea levels slowly inundated Mass Bay, pushing the native populations to settlements along the current shoreline. Prior to the arrival of Europeans on the eastern shores of New England possibly as early as the sixteenth century, the area around Mass Bay was the territory of several Algonquin-speaking tribes, including the Massachusetts, Nauset and Wampanoag

Next page