FIGHTING WITHOUT FIGHTING

FIGHTING

WITHOUT

FIGHTING

KUNG FU CINEMAS JOURNEY

TO THE WEST

LUKE WHITE

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2022

Copyright Luke White 2022

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789145342

CONTENTS

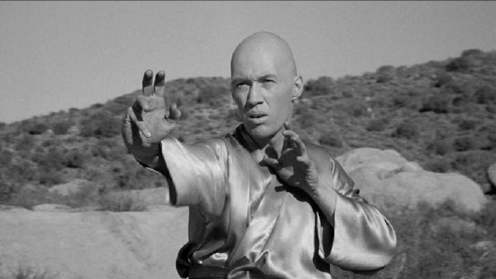

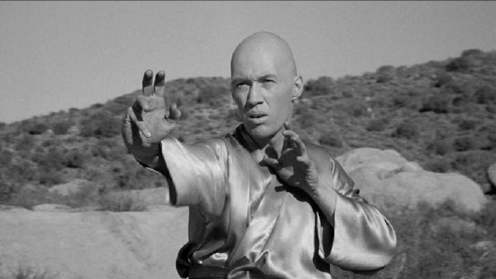

David Carradine in the pilot of the television show Kung Fu, which introduced Western audiences to the novel and exotic ideas, images and mythologies of the Chinese martial arts.

INTRODUCTION

O n 16 May 1973, something unprecedented and since unrepeated in the history of American cinema happened. The entertainment-industry magazine Variety reported that three foreign-language films were sitting at the top of the weeks national box-office charts. Making the event even more extraordinary, these films were all made on what in Hollywood would be considered a shoestring budget. Furthermore, all came from one tiny colony within the last vestiges of the British Empire, Hong Kong. At the time, this was an enclave with some 4 million inhabitants, many of whom lived in third-world conditions, tucked against the side of the Peoples Republic of China (PRC), then still in the grip of Maos Cultural Revolution.

What this curious box-office fact signals is that what became known as the kung fu craze was under way. At number one was The Big Boss (1971), released in the USA as Fists of Fury and starring the charismatic Bruce Lee. At number two was Lady Whirlwind (1972), released under the title Deep Thrust and starring hapkido-trained Angela Mao Ying. At number three, Lo Lieh starred in King Boxer (1972), known in the USA under the lurid and melodramatic title Five Fingers of Death.

Though their impact was slowly declining, Hong Kong martial arts films remained a significant presence in the charts for the rest of the year. It would actually be February 1974, nearly a year after the kung fu craze was launched, before there was a week with no kung fu film listed within them. When Bruce Lees The Way of the Dragon was released in August that year, it still took a million dollars in New York alone in its first five days. Though it certainly remained an abiding passion for some, kung fu cinema would increasingly become a marginal niche. In terms of the box office at least, it seemed that the kung fu craze had already subsided by the spring of 1974, causing the commercial machine of the movie business to move on to exploit fresh fashions.

However, the kung fu craze was much more than a short-lived and quickly forgotten cinematic fad fuelled by the culture industrys eternal quest for novelty. Kung fus journey to the West has a significance that extends beyond its brief life and, moreover, beyond the realm of film history alone. The fascination with Chinese kung fu in particular and the Asian martial arts more broadly that exploded in the early 1970s in America, in the broader West and even across the globe is not only to be found in movies, but has become an enduring presence within a wide range of media from music videos and computer games to comic books and childrens cartoons that continues unabated today.

KUNG FU BEYOND THE MOVIES

Foreshadowing and paving the way for the success of the Hong Kong films was the American-made television series Kung Fu, which starred David Carradine and ran from 1972 to 1975. This told the story of a Buddhist monk from the Shaolin Temple in China who wanders the American West, righting wrongs with a winning mixture of pacifist philosophy and kung fu fisticuffs. It was this series, above all else, that first introduced Western audiences to the mythology around the Chinese martial arts. For the broad public, it even introduced the new and exotic term kung fu itself, which was not commonly understood by English speakers before this time.Goodies devoted an episode, Kung Fu Kapers (24 March 1975), to parodying the craze, inventing the fictional Lancashire martial art of Ecky-Thump, which primarily involved walloping an opponent over the head with a black pudding. From 1976 until 1978, the BBC screened an English dub of The Water Margin, a series shot in China in 19734 by the Japanese company Nippon Television, which adapted a classic Chinese novel of the same name telling the tale of a band of Song-dynasty outlaws. Nippon and the BBC repeated its success with Monkey, adapted from another classic Chinese novel, Journey to the West. This was shown in Japan from 1978 and in the UK, Australia and New Zealand from 1979, and went on to gather a cult following in the countries where it aired.

Pulp adventure novels such as Warren Murphy and Richard Sapirs Destroyer series (starting in 1971) or Dennis ONeil and Jim Berrys Dragons Fists (1974) focused on martial arts within their narratives. Writing in 1974, B. P. Flanigan claimed that over a hundred of these novels had been published since the start of the kung fu boom.

Beyond the entertainment industries, the kung fu craze also sparked an explosion in real-world martial arts instruction, with the movies birthing the desire in audiences across the West to emulate on-screen images of power, grace and freedom. The best-selling author and Bruce Lee fan Davis Miller makes the point even more dramatically:

Before Lees death, there were fewer than 500 martial arts schools in the world; by the late 1990s, owing a lot to his influence, there were more than 20 million martial arts students in the United States alone.

All this suggests that the kung fu craze was not just a matter of films but a much broader cultural phenomenon. It also suggests that in order to understand it, we need to step away from looking solely at film history and towards a wider study of visual and even physical culture. This book thus takes as its object of study a corpus of films and their development, but it also considers how, from the material of Hong Kongs martial arts cinema, a global cultural phenomenon arose. It considers the kinds of meaning and pleasure that the images and iconographies of kung fu took on within American, European and Australasian culture and across the world. How are we to make sense of not only the films, but the craze itself ?

KUNG FUS LEGACY

In attempting to answer this, I do not treat the kung fu craze as an ephemeral fad whose significance ended as the tide of box-office receipts for Hong Kong films ebbed. Rather, kung fu has left a lasting legacy on Western and global culture. This is certainly evident in the narrow domain of film itself. As the kung fu craze waned, Hollywood began to offer a series of home-grown American martial artists as action stars. Blaxploitation films increasingly included karate or kung fu elements, as can be traced clearly in the subsequent career of Lees