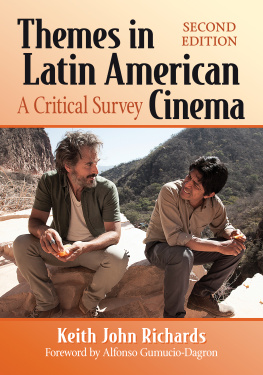

Themes in Latin American Cinema

A Critical Survey

SECOND EDITION

KEITH JOHN RICHARDS

Foreword by Alfonso Gumucio-Dagron

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3776-1

2020 Keith John Richards. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: Companions Andrs (Juan Carlos Valdivia, left) and Yari (Elio Ortiz) in Ivy Marey, from Bolivia (2013)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due first and foremost to all of the twenty-two filmmakers who collaborated with me on this project. Their single most important contribution was to concede interviews, but they also provided useful and interesting dataand, in many cases, invaluable encouragement.

I am also particularly grateful to the following people: Karen Postigo, for her invaluable and endlessly patient help in proofreading. Elizabeth Carrasco at the Cinemateca Boliviana in La Paz has been a boundless source of knowledge and support. The researcher, instructor, translator, and filmmaker Penny Simpson (with Joanne Hershfield, co-director and co-producer of the documentary Nuestra ComunidadLatinos in North Carolina) was enormously helpful with contacts in Mexico, where she worked in cinema, and offered all manner of sound advice. A group-taught course in 2001 at the University of Richmond, Virginia, with my then colleagues, Professors Claudia Ferman and lvaro Kaempfer, was a source of several useful ideas and approaches. Nancy Membrez, at the University of Texas at San Antonio, is another filmmaker in her own right as well as an enthusiast and teacher of Latin American cinema. Nancy has been extremely generous with time and effort in reading and orientation, particularly with the chapter on Eliseo Subielas El lado oscuro del corazn. David Wood at UNAM in Mexico City has helped with several readings and comments, and has made various films and written material available to me.

Several authors have provided texts of entire books or articles on film (Latin American or otherwise). These include Vicky Lebeau, Elissa Rashkin, Mara Jos Somerlate Barbosa, Glen S. Close, Juana Surez, and David Ranghelli. Diego Mendoza Stumpf collaborated with helpful opinions and advice on Deleuze.

Other people who have read chapters creatively and offered invaluable comments include Freya Schiwy, Linda Craig and Josefa Salmn. Two other people at national cinematic institutions were particularly helpful with readings and comments, as well as providing texts and copies of films. Adrin Muoyo at INCAA in Buenos Aires and Eduardo Correa at the Cinemateca Uruguaya in Montevideo helped with advice and data. Patricia DAllemand at QMW in London provided useful suggestions on the books format.

Here in Bolivia I have been helped in various ways by the director Paolo Agazzi, actor David Mondacca, cinematographer Guillermo Medrano, composer Cergio Prudencio, art director Jorge Javier Altamirano, journalist Elizabeth Scott Blacud, academic Ana Rebecca Prada, teacher/poet Juan Carlos Orihuela and librarian/archivists Patricia Surez and Marisol Vargas.

Some of the people who facilitated contact with filmmakers have worked on the productions I analyze, while others have provided information concerning local or national conditions of production. These include Carolina Scaglione and Rafaela Gunner in Buenos Aires, Julin Piz in Mexico, Ricardo Gonzlez Vigil (Lima), Jose Antonio Elizeche (Paraguay), Janaina Bernardes and Srgio Pentiocinas (both in So Paulo).

My heartfelt thanks are due to all of the above.

Foreword

by Alfonso Gumucio-Dagron

To review current Latin American cinema through 23 films is a real challengeone that Keith Richards has taken on with cinematic joy. He has taken the unusual option of analyzing the cinematography of a whole region through the crystal of selected films (to look at film in its own right), putting them at the center of the analysis, though far from oblivious of other considerations.

His choice of films is interesting because unexpected, since he has avoided the usual suspects, focusing on recent works (the oldest is dated 1985) and filmmakers who are mostly better known in their own countries than internationally. He has naturally achieved geographical balance, allowing the reader to discover some countries otherwise nonexistent for the rest of the world in terms of their film production. Many of these films remain unknown in commercial circuits in Latin America, although they are readily available in DVD in the U.S., an added paradox to the choice. In any case, Richards has the merit of revealing them.

Most interesting is that the analysis is grouped under seven sections covering essential themes, and not necessarily the most obvious. From Pre-Columbian Mexico (which actually broadly covers indigenous-themed filmmaking in Latin America) to Poets in the City, a fresh look to Latin American social and cultural reality is offered and Richards succeeds in facilitating a dialogue between the proposed films and the audience/readership, as much as a conversation among the films selected.

The looking-glass is above all that of cultural diversity, recognition that this region is a dynamic and constantly self-transforming entity never frozen within exotic or ethnocentric boundaries. Geography, ethnicity, age, gendernone of these is the main descriptor; culture is. But culture as complexity: a sponge that absorbs conflict and contradiction given that Latin America, like any other region, is a mix of major/minor cultures that have come to share a common space, not often in harmony.

Richards highlights the educational potential of feature films. He joins those who value stories over documentary sources and thinks of fiction film in the same way as those who believe that novels say more about society than history books or academic essays.

The author approaches the subject with an open spirit, from beginning to end. I like that. Contrary to many essays, this one does not force the analysis to fit squarely into a mold that has been elaborated beforehand. Richards did not begin his research with a firm hypothesis that he then tried to prove right all the way to the end. It is clear that he started with curiosity and questions, his perception evolved and his uncertainty grew as he gathered more questions than answers. That is educational.

No less important is how Richards destroys superficial myths and characterizations of Latin America, and does so by quoting sharp writers and filmmakers who reject romantic, tropicalist or patronizing visions.

Humbly, the author announces that the book is made and structured to support the teacher of Spanish language and/or Latin American film, literature or social issues. This may be so, but I believe the end result goes much further and the potential readership is wider than initially sought. Certainly the book is structured as a teaching tool, addressed to those not yet familiar with the subject. However, the methodology can help anyone to enter the realm of current Latin American cinema (if the films are available, which ironically is true for the USA but not for our own region).

Next page