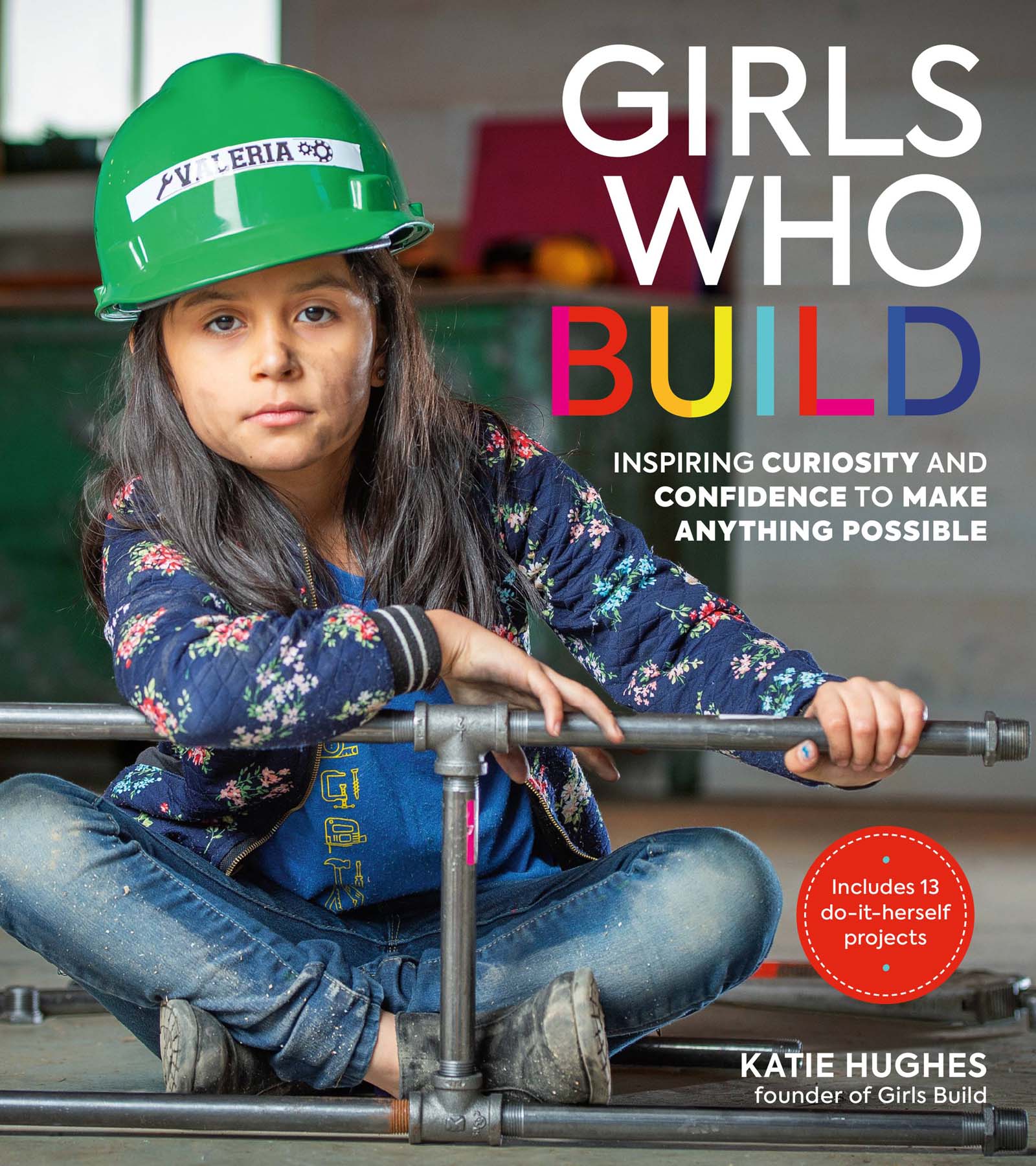

Text and photographs copyright 2020 by Katie Hughes

Illustrations copyright 2020 by Kay Coenen

Cover design by Frances J. Soo Ping Chow

Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

www.hachettebookgroup.com

www.blackdogandleventhal.com

First Edition: October 2020

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers is an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.HachetteSpeakersBureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Additional credits information is .

Print book interior design by Frances J. Soo Ping Chow.

LCCN: 2020930992

ISBNs: 978-0-7624-6721-1 (hardcover), 978-0-7624-6720-4 (paperback), 978-0-7624-6722-8 (ebook)

E3-20201111-JV-PC-COR

DISCLAIMER: Working with tools inherently includes the risk of injury, and projects undertaken based on the information in this book is at your own risk. The author and publisher disclaim any liabilities for any injuries or property damage caused in any way by the content of this book.

I took my first carpentry job when I was twenty-two years old and fresh out of college (or, in my case, fresh off my postcollege AmeriCorps year with Habitat for Humanity) so I could pay rent and eat food. I saw carpentry as a gig, not a career. My career, I thought, would involve sheltering the shelterless, feeding the foodless, or doing anything befitting a humanitarian posterthe kind of work my social work degree had promised. But in the meantime, I was happy to swing a hammer, fine-tune my woodworking skills, and learn from a man who quickly became my mentor and friend.

Id built a good base of house-framing knowledge from my AmeriCorps supervisor, Ray, who teased us by saying, Some bosses are tough and ruthless; Im just rough and toothless. Calling Ray rough is a stretch. He was funny and kind, believed that the three women on his crew were equal to the men, and took it in stride when we pointed out the ways we werent treated as such. I fell in love with building that year and started on an unexpected career, one that was actually rooted in my childhood. In a way, Girls Buildthe nonprofit I eventually founded to teach girls to gain skills and confidence in the tradesgrew out of that foundation too.

The first time I used a tool, I was about two or three. My dad, Jim, had died tragically and suddenly at the age of thirty-seven after an on-the-job fall from a telephone pole. At the time, I was just a tiny heartbeat in my moms womb; she intended to surprise my dad by announcing her pregnancy to him on a Christmas card. He had no idea my mom was pregnant.

What we had left of him was a garage full of tools that he had loved and had used to build our house and fix our many broken cars and make a cradle, a dollhouse, a rocking horse, and whatever else struck my two older sisters whims. Those tools were symbols of his love and affection for my sistersand for me, too, I always believed. Hed held them in his hands for hours and hours. Our hands could touch those same spots, hold his tools in the same way, and we could feel a little of what he might have felt as he built for us. It seemed, just a tiny bit, like he was there with us.

The first project I remember tackling was our front-yard tree fort, complete with a swing and a cat elevator. I was three years old. Bridget, four years my senior, was the project manager. She guided my pudgy hands onto the drill, helping me bore holes into a 2x6 for our swing. Then, later, she handed me Daddys hammer, our most precious of all his tools, along with a scoop of nails. I nailed up some of the steps that led us precariously into the upper reaches of the tree.

Of the whole fort, though, the cat elevator was the most important piece, precisely because it was the most ridiculous. First, to get this point out of the way, yes, cats have built-in elevators commonly called claws that they use daily to climb trees. Apparently, according to us, our cat, Bubbles, needed something fanciersomething in the form of two thin ropes thrown over a tree limb with loops at the bottom. We would slide poor Bubbles into said loops, then haul her up into the fort. She hated it, but we thought we were ingenious.

The imagination involved in creating that cat elevator is what I attempt to encourage at our Girls Build summer camps. I want girls to leave feeling like they could build something as absurd and unnecessary as a cat elevator. I want them to draw it out on paper, on a whiteboard at school, or on the sidewalk in chalk. I want them to make Popsicle-stick models of it, fold an origami version of it, or do whatever else they feel like doing. I want them to be excited and inspired by a product of their own creativity. I want them to go home and build a freaking cat elevator.