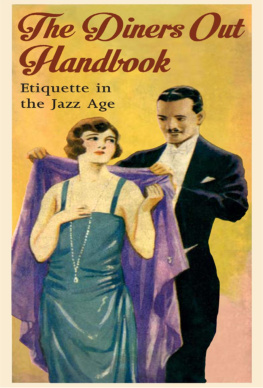

THE

DINERS OUT HANDBOOK

A POCKET HANDBOOK ON

THE MANNERS AND CUSTOMS OF SOCIETY FUNCTIONS PUBLIC AND PRIVATE DINNERS , BREAKFASTS , LUNCHEONS , AFTERNOON TEAS , AT - HOMES , RECEPTIONS , BALLS AND SUPPERS , WITH HINTS ON ETIQUETTE , DEPORTMENT , DRESS , CONDUCT , SELF - CULTURE , HEALTH , COURTSHIP AND MARRIAGE , AFTER - DINNER SPEAKING , ENTERTAINMENT , STORY - TELLING , TOASTS AND SENTIMENTS , INDOOR AMUSEMENTS , ETC ., ETC ., ETC .

BY

ALFRED H. MILES

PREFATORY

T HIS little book is an attempt to help the young and inexperienced to the reasonable enjoyment of the social pleasures of society by an elementary introduction to the rules and regulations which govern its functions, and a brief indication of the principles of chivalry and morality which underlie their enactment and exaction. It makes no claim to be a complete treatise on any one of the numerous subjects with which it incidentally deals, but its first word was written with the hope, and its last with the conviction, that it will serve a useful purpose by giving in a popular form, a great deal of suggestive information which may be pleasant and profitable to the reader, and through him to those with whom he may come in contact. Had more space been available the writer would have treated some subjects in greater detail, and have dealt with one or two others which might with some appropriateness have been included, but the inexorable limits of the reasonable pocket, which should never be allowed to disturb the symmetry of an exact fit, imposed conditions which could not be disregarded without danger to that perfect equipment which it is the books object to promote. Whos Who? is a very comprehensive handbook of society nomenclature, but no fashionable tailor would undertake to accommodate it in the pocket of a dress-coat. Such as it is, the writer leaves his book in the readers hands, hoping that it may be some small help to his enjoyment.

A. H. M.

CONTENTS

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

THE DINERS OUT VADE-MECUM

DINNER is the most important as well as the most substantial meal of the day. It marks the meridian of gastronomic time, and all other meals are regulated by it. It offers the largest variety of food, and occupies the longest measure of time, and, if only on this latter account, deserves the most attention. In all ages feasting has been associated with both public and private rejoicing, and the evening meal has ever been the most esteemed. Abraham celebrated the weaning of Isaac with a great feast. Laban gathered together all the men of the place and made a feast to honour the marriage of Jacob, and Pharaoh kept his own birthday by giving a feast to his servants. Other occasions of the feasts of old were the consummation of the harvest and the vintage, the summer and the winter solstice. The Roman feast was always a supper, and commonly commenced at about three oclock in the afternoon. These were often great occasions, and were protracted to a late hour. Julius Caesar once gave entertainment to 22,000 guests, and the feast was enlivened by music, dancing, and gladiatorial exhibitions. The feasts of the Hebrews were varied by music, poetry, storytelling and the solution of riddles. It is interesting to note how many of these old customs survive in our modem practices.

DINERS may be classified as diners-in and diners-out. The diner-in is the host who gives the dinner, and in the majority of cases the guests are those who in their turn are diners-in, and who on such occasions reciprocate his hospitality. Besides these, however, there are others, bachelors and spinsters, visitors from abroad, or from a distance, who are welcomed for a variety of reasons, and from whom no invitation is expected in return. It is to these latter, and especially to the bachelors, that this little book is addressed.

ETIQUETTE is the accepted code of manners observed by good society. Its object is not restraint, but graceful freedom.

To be entirely at ones ease, without impairing the complete ease of others, is to secure the whole purpose and intent of etiquette.

He who has mastered the golden rule, As ye would that others should do unto you, do ye unto them, has acquired the true spirit of etiquette, though he may yet have much to learn as to its application to the various experiences of life.

Like the laws of art, the laws of etiquette are deduced from the principles and practices observed by the best masters, and, like communal laws, they came into being in the first instance for the protection of the weak. It was to protect the weak against the strong of the community that communal laws were first enacted, and modern etiquette is an outcome and a survival of the olden spirit of chivalry, which led the brave to deserve the fair. To this day the gentleman is always presented to the lady, however noble his rank may be, and however lowly hers, and this is not done until it has been ascertained that the introduction will be agreeable to her.

Indiscriminate introductions are a sure sign of vulgarity, and no introduction should ever be made without the assurance that it will be agreeable to both parties.

The whole practice of good manners is based upon the gracious bearing of the higher to the lower in the social scale, and the equally gracious recognition of the accepted order of precedence on the part of the lower to the higher. When these obtain, both meet upon a common ground of practical understanding, without loss of dignity on either part.

Some of the earliest and best rules of etiquette may be traced to the early Christian writings and one lesson given in St. Luke xiv. 8-11 is so applicable to the diner-out to-day, that we venture to quote it here.

When thou art bidden of any man to a marriage feast, sit not down in the chief seat; lest haply a more honourable man than thou be bidden of him, and he that bade thee and him shall come and say to thee, Give this man place; and then thou shalt begin with shame to take the lowest place. But when thou art bidden, go and sit down in the lowest place; that when he that hath bidden thee cometh, he may say to thee, Friend, go up higher: then shalt thou have glory in the presence of all that sit at meat with thee. For every one that exalteth himself shall be humbled; and he that humbleth himself shall be exalted.

In honour preferring one another is also a time-honoured maxim which may well be observed in general practice.

For special occasions, special laws are laid down, and these should be duly observed; but circumstances will often arise when it may be difficult to apply any specific rule, and these will be found to be the real opportunities and tests of good manners. To break a law of etiquette may be the misfortune of many not well versed in the procedure of good society, or new to the particular experience in passing; but in such cases it is always the duty of the master of deportment to observe the spirit which underlies all laws of good behaviour by refusing to, be perturbed by untoward incident, and declining to accentuate awkwardness at the expense of the offender. To observe the laws of etiquette is to act at least after the manner of a gentleman, but to intentionally humiliate another who has unfortunately transgressed is to display the spirit of a cad.

ROYAL MANNERS.A certain architect unaccustomed to association with royalty was once called upon, in the pursuit of his professional duty, to hand a silver trowel to H.M. King Edward VII., at that time Prince of Wales, in order that he might well and truly lay a certain foundation-stone. The architect was an extremely nervous man, and looked forward with some trepidation to the, to him, formidable ordeal. His fears, however, were quite illusory. He was dealing with a master of deportment, who immediately on his arrival at the scene of the ceremonial, sent for him, complimented him upon the designs he had prepared for the building about to be erected, and put him so entirely at his ease that the function became a pleasure instead of a pain.