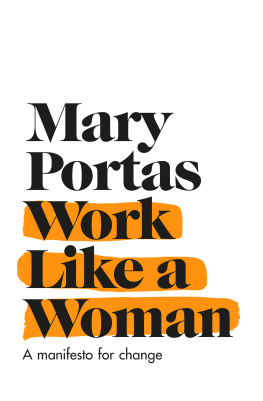

HOW TO THINK LIKE A WOMAN

HOW TO THINK LIKE A WOMAN

Four Women

Philosophers Who

Taught Me How to Love

the Life of the Mind

REGAN PENALUNA

Grove Press

New York

Copyright 2023 by Regan Penaluna

Jacket design by Kelly Winton

Jacket artwork Ewa Juszkiewicz. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

First Grove Atlantic hardcover edition: March 2023

This book was set in 11.5 pt. Scala Pro by Alpha Design & Composition of Pittsfield, NH.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-5880-2

eISBN 978-0-8021-5881-9

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

For my parents, my sisters, and Iowa

We cannot live in a world that is interpreted for us by others. An interpreted world is not a hope. Part of the terror is to take back our own listening. To use our own voice. To see our own light.

Hildegard of Bingen, 10981179

Contents

Note

T he seed for this book was planted when I was thirty-one years old and newly divorced. I had just resigned from a full-time job with benefits as a professor of philosophy and moved out of my home near the Upper Iowa River. Id invested over a decade in a life of the mind only to trade it all in for a small, cockroach-ridden apartment in New York City and an adjunct teaching job with no security and a ninety-minute commute. All the same, I knew if I didnt make the move, Id break.

Once, being an academic philosopher had held the promise of making me into the person I always imagined Id becomesomeone authentic, driven by her own compass. It would, I believed, fulfill my childhood dream of jumping headfirst into a life devoted to questioninga life that would lead me to places of exceptional intellectual endeavor and beauty. It promised a career that would give me independence.

The truth is, philosophy is a hard place to make a career, but its especially hard for a woman. The odds are against her from the start. It is a subject dominated by white men, many of whom arent much concerned about the fields long history of oppression and how that oppression is still alive today, pulsing through texts, customs, habits of thinking, and behavior. The result is a climate that is unfriendly, sometimes even hostile, to women.

Philosophy has been and is still very much a field where youre rewarded for thinking in a way that ignores or is detrimental to women. I believe this is a problem in philosophy, where greatness is rarely, if ever, expected of women. Rather than taking responsibility for the hostile climate, some men in the field simply doubt womens intellects.

These men see women primarily as a sex rather than as individuals. These men also see womens underrepresentation in philosophy as a result of choices women have made to study other things in an otherwise fair world rather than as evidence of women making decisions in a world that is in many ways limited to them or working against them. But most of all, they dont acknowledge that their skepticism of womans intellectual capacityexpressed casually and with an objective airimpacts the self-perception and lives of actual women.

The word philosophy is from the ancient Greek and means the love of wisdom, a pursuit, in theory, available to any curious, determined human being. Ideally, philosophy reflects human thought at its greatest magnitude and embodies a cultures quest for truth and self-knowledge. It matters that this endeavor has fallen short not only of truth but also of justice on several counts, including the treatment and understanding of women. Philosophers have been some of the most consistent and fruitful contributors to theories of womens inferiority, treating topics traditionally studied by women, such as parenting, caregiving, and other aspects of domestic life, with little interest, while the white male point of view is dramatized in countless thought experiments.

Of course, not all philosophy is like this. Feminist philosophy, critical race theory, and Queer theory all challenge the dominance of this view. In my experience, the problem is that these schools of thought are neither mainstream nor regularly taught in introductory courses; if they are on offer at all, it is typically as elective courses. In college philosophy departments, the mark of a serious philosopher is whether he knows his epistemology, metaphysics, and ethicsnot, for example, his feminist philosophy, which is still largely dismissed as a political rather than a philosophical endeavor. Yet any person who knows their Nietzsche or has carefully studied the history of philosophy recognizes the hubris behind the assumption that some areas of philosophyincluding the most abstractare necessarily free of bias.

In this light, perhaps its no surprise that some women report feeling uncomfortable speaking up in philosophy classes. Perhaps its also not surprising that there are fewer women in senior positions in philosophy than in any other field in the humanities and in many of the sciences as well.

The plight of women in philosophy is part of a much larger story of the suppression of individuals who are not white, male, heterosexual, cis, and able-bodied. For instance, works by Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC) make up only 3 percent of articles published in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , and from 2003 to 2021, Black academics contributed only 0.32 percent of all papers published in the top fifteen philosophy journals. I suspect a major reason there arent many women and minorities in philosophy is because the double standard of justification is simply too exhausting. On top of teaching, researching, and fulfilling departmental duties, these individuals are under constant pressure to prove that they belong there in the first place.

These issues of inclusion and fairness were not at the top of my mind when I began studying philosophy. But my perspective started to shift when I accidentally came across the work of a woman philosopher from over three hundred years ago. I realized I didnt know of any women philosophers who had lived prior to the twentieth century. I also realized, abashedly, that I didnt know anything about the women philosophers of the twentieth century except their names. No one in my department studied or taught them; we didnt even have a course on feminist philosophy. I had internalized the misogynist notion that because none of them were being taught, none of them were worth looking into.

I was wrong. Over the next few years, I read about the lives and work of four brilliant and inspiring female philosophers: Mary Astell, Damaris Masham, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Catharine Cockburn. I discovered that in a time when women were forbidden to study at universities and male philosophers wrote extensively about the intellectual shortcomings of the female mind, these women pushed back. They highlighted the double standards of philosophers who promoted Enlightenment ideals of freedom and equality but did not extend those ideals to women. In reading about their works and lives, I started to reconnect to something deep inside myself. Astell, Masham, Wollstonecraft, and Cockburn were heroic voices from across time cutting through my frustration.