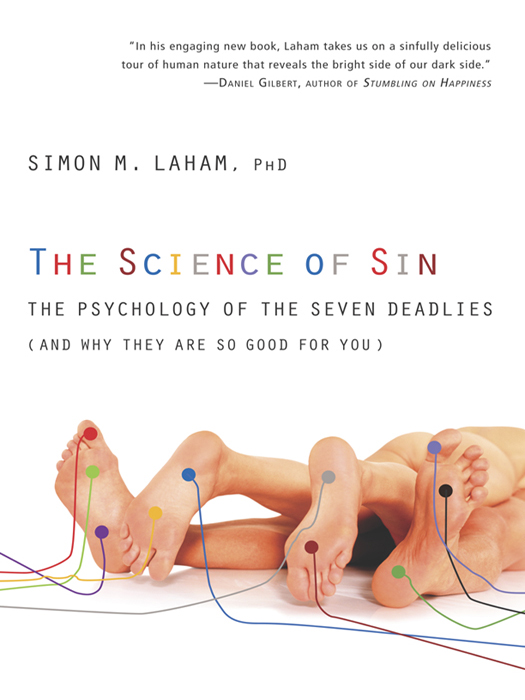

Copyright 2012 by Simon M. Laham

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Three Rivers Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Three Rivers Press and the Tugboat design are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Brookings Institution Press for permission to reprint an excerpt from Economic Growth and Subjective Well-Being: Reassessing the Easterlin Paradox, Brookings Papers, Spring 2008 by Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers. Reprinted by permission of Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC, www.brookings.edu.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Laham, Simon M.

The science of sin : the psychology of the seven deadlies (and why they are so good for you) / Simon Laham.1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Pleasure. 2. Deadly sinsPsychology. 3. VicesPsychological aspects.

I. Title.

BF 515. L 34 2012

150dc23 2011017275

eISBN: 978-0-307-71935-5

Cover design by Jessica Bright

Cover photographGetty Images

v3.1

CONTENTS

Introduction

I confess it; I am a sinner. I greet most days with a mix of sloth and lust (which, coincidentally, is also how I end most days); this morphs into mild gluttony over breakfast and before I know it Ive been condemned to hell several times over, and its not even nine A.M. Pride, greed, sloth, gluttony, lust, envy, and anger, the seven deadly sinsthese are my daily companions.

And you? Are you a sinner? Can you think of a single day in your life during which you didnt indulge in at least a few of these vices? I bet you cant.

The simple fact is that we all sin, and we do it all the time. We lie and we cheat and we covet all manner of things, from our neighbors wives to their bedroom suites. But fear not: The seven deadly sins arent as bad for you as you might think. From gluttony to greed, to envy and lust, even these deadliest of vices can make you smart, successful, and happy. At least thats what Ill try to convince you of by the end of this book.

The seven deadly sins are ubiquitous. Geographer Thomas Vought, of Kansas State University, recently examined Americas sinscape, mapping the sinful peaks and vice-filled valleys of counties across the United States.seven deadly sins are alive and well. Here, by the way, are the winners:

Most proud: Shreveport, Louisiana

Most greedy: Las Vegas Strip

Most slothful: Atlantic City, New Jersey

Most gluttonous: Tunica Co./Lula, Mississippi

Most lustful: Tunica Co./Lula, Mississippi

Most envious: Biloxi, Mississippi

Most angry: Shreveport, Louisiana

If everyone is indulging, why do the sins have such a bad name? Well, its mostly the fault of Pope Gregory the Great. In his A.D. 590 book, Morals on the Book of Job, Gregory gave his short list for the deadliest sins. He didnt invent the list, mind you; he simply refined previous efforts: those of the monks Evagrius Ponticus and John Cassian.

The deadly sins grew out of the monastic life of the early Middle Ages, when they were codified in an attempt to keep monks from running amok and quitting their spiritual calling. In short, the deadly sins were practical guidelines for maintaining the social order within ascetic communities. Monastic leaders didnt want a bunch of gluttons on their hands; there was, after all, not much food to go around. Neither did they want slothful, proud, or envious monks who would happily give up the hardships of the religious life as soon as they ran across a minor spiritual speed bump.

The sins may have been codified in monasteries, but they have since been ingrained in the cultural consciousness of Western civilization. Pope Gregorys list established the deadly sins in the Western world as any but your run-of-the-mill transgressions. Indulge anger or envy, and the penalty was not simply a slap on the wrist. These were serious offenses that could land you an eternity in hell. And this is what much of the Western world has thought about the seven deadly sins ever since. For centuries, the deadlies have exerted a powerful influence on the Western imagination, scaring the hell out of (or rather into) children and adults alike and infiltrating all corners of our culture, from the writings of Chaucer, Dante, and Milton to the movies of David Fincher.

In the psychological sciences, however, the concepts of sin and morality have quite a different history. Over the years, philosophers and scientists have made attempts to naturalize morality, stripping any divine gloss from the concept. Morality is now considered a set of evolved mechanisms that serve useful evolutionary ends. As are the traditional sins. In psychology, pride, lust, gluttony, greed, envy, sloth, and anger arent considered sins, or morally wrong, or even uniformly bad, but rather are complex and largely functional psychological states.

Each of the deadly sins does, of course, have its downsides, but each also has a range of positive, useful effects: anger breeds perseverance; sloth, helpfulness; greed, happiness; and envy can bolster self-esteem. In short, when it comes to the seven deadly sins, the picture is a complex one.

It is this complexity that I want to explore over the following seven chapters. The simplistic labeling of the seven deadly sins as sins or as uniformly wrong does nothing but breed contempt for sinners and stifle sophisticated discussion. This book rails against this kind of simplicity.

I have another confession to make: I am an experimental social psychologist. This means that I study human social behavior (especially moral behavior) by bringing people into the laboratory, manipulating some aspect of their thinking or action, and then watching what happens. This approach to studying behavior has proved fruitful in understanding much of what makes us tick. And it is this kind of work that forms the backbone of this book. Each chapter covers an array of psychological research that demonstrates the fascinating complexity of the seven deadly sins.

You may be thinking that people dont really consider the deadly sins as sins anymore. Well, lets not get ahead of ourselves. Many still take religious doctrines as quite literal guides for living.

Nevertheless, some of us probably dont consider eating too much or lazing around as prerequisites for entry to hell. The fact is, however, that the long cultural history of the seven deadlies as sins has left them with a grimy residue of negativity that is rather hard to wash off.

Consider the results of the following study. William Hoverd, of the Victoria University of Wellington, and Chris Sibley, a psychologist at the University of Auckland, wanted to know whether people still think of sloth as immoral. To do this, they gave participants whats called an Implicit Association Test (IAT), a computer task designed to measure how closely two concepts are associated in the mind. Heres how the IAT works.

Imagine youre seated in front of a computer screen. On the left of the screen you see two category labels: flowers and pleasant. On the right of the screen you see two more labels: insects and unpleasant. Your task is to categorize target words that appear in the center of the screen into their appropriate categories by pressing a key with your left hand if the word belongs to a category on the left (flowers or pleasant) or with your right hand if the word belongs to a category on the right (insects or unpleasant). So the task proceeds: Tulip flashes on the screen and you press the left key, then ugly flashes up and you press the right key. These responses should be pretty straightforward. Because flowers and pleasant are quite closely associated in the mind (we all like flowers, right?), you should find it easy to respond to these categories using the same key. (The same goes for insects and unpleasant). The more strongly linked two concepts are, the easier it should be to respond to them when they form a single unit (i.e., are on the same key).