Analysing English as

a Lingua Franca

Also available from Continuum

Corpus-Based Approaches to English Language Teaching Edited by Mari Carmen Campoy-Cubillo, Begona Bells-Fortuno and Maria Llusa Gea-Valor

Globalization and Language in Contact Edited by James Collins, Mike Baynham and Stef Slembrouck

Language, Culture and Identity Philip Riley

Multilingualism Adrian Blackledge and Angela Creese

Second Language Identities David Block

Using Corpora in Discourse Analysis Paul Baker

Analysing English as a Lingua Franca

A Corpus-driven Investigation

ALESSIA COGO AND

MARTIN DEWEY

CONTENTS

ABBREVIATIONS

American English (AmEng)

British English (BrEng)

British National Corpus (BNC)

Communicative Language Teaching (CLT)

Conversation Analysis (CA)

English as a Foreign Language (EFL)

English as a Lingua Franca (ELF)

English as a Lingua Franca in Academic Settings (ELFA)

English Language Teaching (ELT)

English as a native language (ENL)

International Corpus of Learner English (ICLE)

Native Speaker (NS)

Non-Native Speaker (NNS)

Vienna Oxford International Corpus of English (VOICE)

Introduction

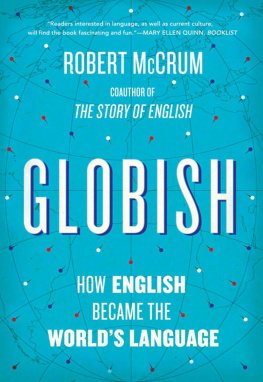

Introducing English as a lingua franca

In the past 20 years or so the phenomenon of globalization has had a profound effect on the profusion of English in the world. Recent technological and demographic developments have contributed to the ongoing internationalization of the language, ultimately changing not only the way it is used, but also the way it is conceptualized. Like any other language, English is involved in natural processes of variation and change; but the conditions under which these currently occur in English have intensified as it comes into increased contact with other languages and is spoken by increasingly diverse users across many varied communities. The extent to which the language has diversified on a global scale is entirely unprecedented. This rather distinct sociolinguistic reality makes English as a lingua franca (henceforth ELF) a phenomenon that is sui generis, and one which therefore requires a different methodological and theoretical perspective for conducting empirical research.

Researching ELF is a relatively recent empirical enterprise. In a sense, the use of English for lingua franca communication is nothing particularly new. English has been spoken for this purpose for many centuries (at least since the earliest British colonial activities from the 1500s onwards), as have numerous other lingua francas currently spoken in the world. In fact, the use of linguistic codes as a means of interacting in heterogeneous language contact situations have probably always existed as important phenomena in human interaction (see e.g. Ostler, 2005). Yet, in the contemporary use of the term ELF, we are talking about a research paradigm that has only really developed during the last ten years or so.

The beginnings of ELF empirical work can probably best be described as occurring with two seminal publications that appeared in fairly quick succession, Jenkins (2000), a book-length empirical study of phonology in ELF, and Seidlhofer (2001), a conceptual paper calling for large-scale systematic investigation into what was already the most extensive contemporary use of English worldwide (p. 133). The study of ELF as a valid research undertaking really began to flourish following this paper, in which Seidlhofer puts forward a powerful case in arguing that linguistic description of ELF was an absolute necessity if the growing awareness of the sociopolitics of English globally (see e.g. Hall and Eggington, 2000) were to have any impact on the continued use of NS norms, still universally applied regardless of sociolinguistic context. Prior to this, the mid to late 1990s saw several relevant publications with a research focus on the use of English in lingua franca settings (most significantly Firth, 1996; House, 1999; and Jenkins, 1998), but these were somewhat isolated attempts to document ELF, and in the case of the former two were undertaken from slightly different perspectives and with varying approaches.

It was thus only after the turn of the millennium that ELF properly began to establish itself as a distinct area of systematic empirical work with a more coherent set of theoretical assumptions and methodological practices. We have positioned the research findings reported in this book very much in line with these emerging theories and methods. The theoretical and analytical approach adopted here has been directly influenced by both Jenkins (2000) and Seidlhofer (2001), and we see our work as belonging to the research paradigm that has emerged partly in response to these two milestone publications.

ELF research to date

The early focus of ELF-oriented research was the sociolinguistic description of language forms (phonological, lexical, grammatical and pragmatic) of English in lingua franca interactions. ELF research to date has predominantly focused on providing descriptions of naturally occurring speech (there is a growing interest in the study of writing from an ELF perspective, although there is still little data available to date). By contrast to earlier studies involving classroom simulations, empirical work in ELF has been very firmly oriented towards investigating un-elicited lingua franca talk. Following the approach taken in Jenkins (2000), which was primarily concerned with identifying which phonological forms are essential for mutual intelligibility (although importantly this work also included a lengthy consideration of the role of accommodation in ELF), most of the initial subsequent research was very much focused on the formal properties of ELF for the purpose of identifying its primary linguistic characteristics. This was also certainly the starting point, at least, for the data reported in this book.

As ELF has continued to develop as a distinctive field, however, the trend more recently has been for researchers to shift the focus away from identifying the features of ELF talk themselves towards an interest in the underlying processes that give rise to the emerging forms (a matter taken up further in realization that ELF communication is by nature especially fluid, and that speakers use of linguistic forms especially variable (see the studies reported in Mauranen and Ranta, 2009).

The emergence of ELF corpus work has by now become widely established. The first major corpus dedicated to ELF, the Vienna Oxford International Corpus of English (VOICE), was launched in 2001 and then became publicly available in May 2009 (accessible at www.univie.ac.at/voice). Shortly after the launch of VOICE, Mauranen (2003) announced another major ELF corpus, the corpus of English as a Lingua Franca in Academic Settings (ELFA). Both these corpora, VOICE and ELFA are 1 million+ word databases of transcribed spoken interactions. More recently, we have seen the launch of another large-scale corpus project, Asian Corpus of English (ACE) under the direction of Andy Kirkpatrick at The Hong Kong Institute of Education, and with researchers working throughout East and South East Asia (Kirkpatrick, 2010a). In addition, there is a growing number of smaller corpus-based projects around the world, especially doctoral thesis-based studies. In other words, the body of ELF data available for analysis is already quite substantial, and more importantly, it continues to expand as the field continues to mature.