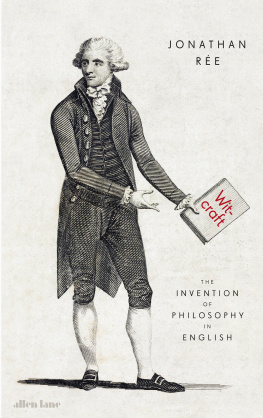

Jonathan Re

WITCRAFT

The Invention of Philosophy in English

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2019

Copyright Jonathan Re, 2019

Cover image: Thomas Paine, Author of Rights of Man. Photo Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Cover design by Jim Stoddart

Endpapers: Detail of a biographical chart from William Enfields The History of Philosophy, 1791, vol. 1 (from the collection of the author

ISBN: 978-0-241-00365-7

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Illustrations

. Table of places from Blundevilless Arte of Logike (1599). (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

. Ramuss method of dichotomies, from Fraunces Lawiers Logike (1588). (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

. The sun and earth, from Brunos De Umbris Idearum (1582). (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

. Descartess Discourse of a Method (1649). (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

. Descartess Passions of the Soule (1650). (Copyright British Library Board)

. Logical analysis in Algonquin, from Eliots Logick Primer for the Indians (1671). (Copyright British Library Board)

. Philosophical chronology from Stanleys The History of Philosophy. (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

. Engraving by Samuel Wale of the Act of Settlement of 1701. (Copyright Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

. Molyneuxs translation (1680) of Descartess Meditations. (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

. John Locke, by Michael Dahl (1696). (Copyright National Portrait Gallery)

. Frontispiece to Hildrops Essay for the better regulation and improvement of free-thinking (1739). (Copyright British Library Board)

. Miniature of William Hazlitt, by his brother, John (1786). (Photo by Paul DixonMaidstone Museum & Bentlif Art Gallery)

. Charles Lamb, by William Hazlitt (1804). (Copyright National Portrait Gallery)

. Self-portrait by William Hazlitt (1802). (Copyright Maidstone Museum & Bentlif Art Gallery)

. William Hazlitts portrait of his father (1801). (Photo by Paul Dixon; copyright Maidstone Museum & Bentlif Art Gallery)

. Kant made easy, from Wirgmans Principles of the Kantesian or Transcendental Philosophy (1824). (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford)

. Portraits by Cara Bray of Robert Evans and his daughter Marian (1841). (Copyright National Portrait Gallery)

. William James at Chocorua (1891). (Houghton Library, Harvard University)

. Wilkie James, by William James (1863). (Houghton Library, Harvard University)

. Self-portrait by William James (1866). (Houghton Library, Harvard University)

. Hilltop Cottage, Glenmore (1892). (University of Chicago Library)

. Cover and Pholisophical Advertisements from Mind! (1901). (Collection of the author)

. Wittgenstein outside his school at Puchberg (1924). (Copyright Wittgenstein Archive Cambridge)

Thanks

In 1993 Radical Philosophy brought out an essay of mine on English Philosophy in the Fifties and the publisher Philip Gwyn Jones suggested that it could be expanded and turned into a book. A quarter of a century later, here it is. During that time I have run up many other debts of gratitude: to Middlesex University, Roehampton University, the Royal College of Art, the Leverhulme Trust, the Clark Art Institute, and the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton; to Stuart Proffitt, Ben Sinyor and Richard Duguid at Penguin, Jennifer Banks at Yale, and Jacqueline Ko and James Pullen at Wylie; to staff at dozens of libraries, especially the Bodleian and the British; and to Michael Ayers, Wendy Carlin, Jane Chamberlain, Mark Handsley, Chris Lawn, Josef Mitterer, Ananda Pellerin, Janet Re, Ulrich Johannes Schneider, David Wood and Stephen Yeo; above all to Christiane Gehron and Lotte Re.

Introduction: towards a revolution

The first work of philosophy to make an impression on me was a short book by Jean-Paul Sartre called Existentialism and Humanism. Much of it went over my head, but I got the main message: our knowledge will never be perfect, the world means nothing until we apply our interpretations to it, and we should dare to live our lives in freedom like an artist facing a blank canvas rather than a functionary filling in a form. I was fourteen at the time, and this all struck me as true and exciting. (It still does.) Philosophy was about questioning received ideas, and I wanted more.

I turned first to Descartes, who according to Sartre had anticipated him with his declaration I think therefore I am. I had no idea what that could mean, but the stationery shop in the London suburb where I lived had a philosophy section (this was the 1960s), and I bought myself a paperback of the essential writings of Descartes. The portrait on the cover looked grim, and Descartess reflections on God and human knowledge seemed contrived and unbelievably dull. I could not imagine what Sartre saw in him. I needed help.

I went back to the shop and found several books on the history of philosophy. They promised to cover the whole thing from its origins to the present, which sounded almost too good to be true. The first one I reached for was by Bertrand Russell, who was famous at the time for having impeccable principles and the finest brain in the world. A glance at his History of Western Philosophy seemed to confirm his brilliance: was there anything he had not read, any problem he could not solve? Russells researches had led him to the conclusion that philosophy got under way in ancient Greece: philosophy begins with Thales, as he put it, and he then delivered a tirade against the obvious errors of Plato. Philosophy seems to have sunk into some kind of torpor in the Middle Ages, but it perked up with Descartes a man of high philosophic capacity who became the founder of modern philosophy. Russell then continued the story to his own time, in fact to himself. I marvelled at his mastery of the philosophical universe and the assurance with which he passed judgement on his predecessors, and I wondered if I would be able to do that sort of thing when I grew up. But he had nothing to say about Sartre or what he might have got out of Descartes, so the book went back on the shelf.

Nearby I came across a couple of books on philosophy in a series called Teach Yourself. They too promised to tell the story from beginning to end, and they were short and cheap so I bought them both. In