Contents

Engines of Privilege has two underlying premises: that the existence in Britain of a flourishing private school sector not only limits the life chances of those who attend state schools, but also damages society at large; and that it should be possible to have a sustained and fully inclusive national conversation about the subject. Whether one has been privately educated, or has sent or is sending ones children to private schools, or even if one teaches at a private school, there should be no barriers to taking part in that conversation. Everyone has to live and make their choices in the world as it is, not as one might wish it to be. That seems an obvious enough proposition. Yet in a name-calling culture, ever ready with the charge of hypocrisy, this reality is all too often ignored.

For the sake of avoiding misunderstanding, we should state briefly our own backgrounds and choices. One of our fathers was a solicitor in Brighton, the other was an army officer rising to the rank of lieutenant-colonel; we were both privately educated; we both went to Oxford University; our children have all been educated at state grammar schools; in neither case did we move to the areas (Kent and south-west London) because of the existence of those schools; and in recent years we have become increasingly preoccupied with the private school issue, partly as citizens concerned with Britains social and democratic wellbeing, partly as an aspect of our professional work (one as an economist, the other as a historian).

In an important sense, none of this matters. Rather, what matters infinitely more is the issue itself. That is the subject of this book. Britains private schools including their fundamental unfairness remain a major elephant in the room, perhaps the biggest of all. It would be an almost immeasurable benefit if this were no longer the case. And our hope is that this book, by discussing in a sober, historically aware and evidence-based way both the problem itself and possible remedies, will contribute to a new openness for objective, guilt-free debate. It is, after all, high time.

July 2018

Education is different. Its effects are deep, long-term and run from one generation to the next. Those with enough money are free to purchase and enjoy expensive holidays, cars, houses and meals. But education is not just another material asset: it is fundamental to creating who we are. If we buy an expensive and exclusive schooling for our children, we influence how they grow, the sort of people they will become and what they will do. On top of that, the qualifications they gain haul them further up the ladder to scarce, rewarding places, first at our elite universities and then later in life. So by making that purchase, we are at the same time buying significant positional advantage for our children at the expense of other childrens futures. Put plainly, the purchase of private education by a minority of us is incompatible with the pursuit of a fairer, more cohesive society: an inconvenient truth, but the truth nonetheless. Education, to repeat, is different.

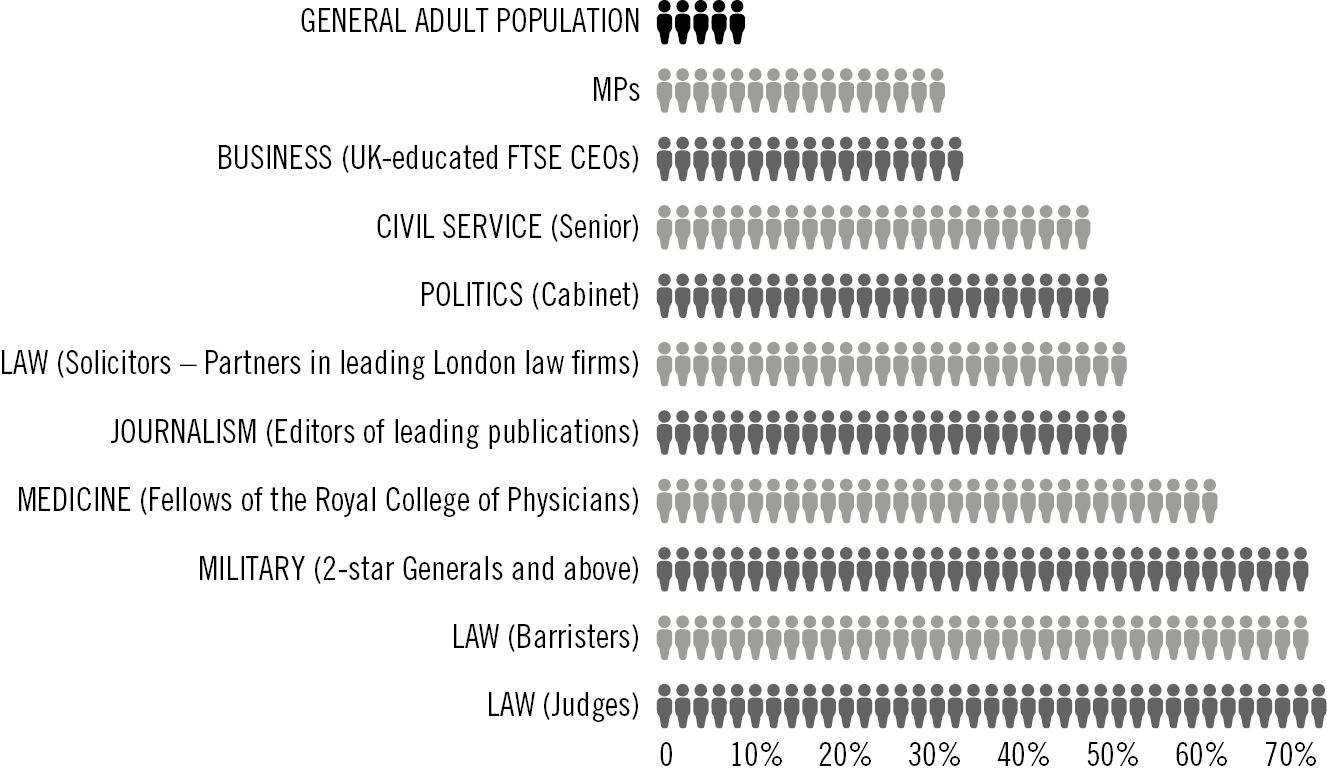

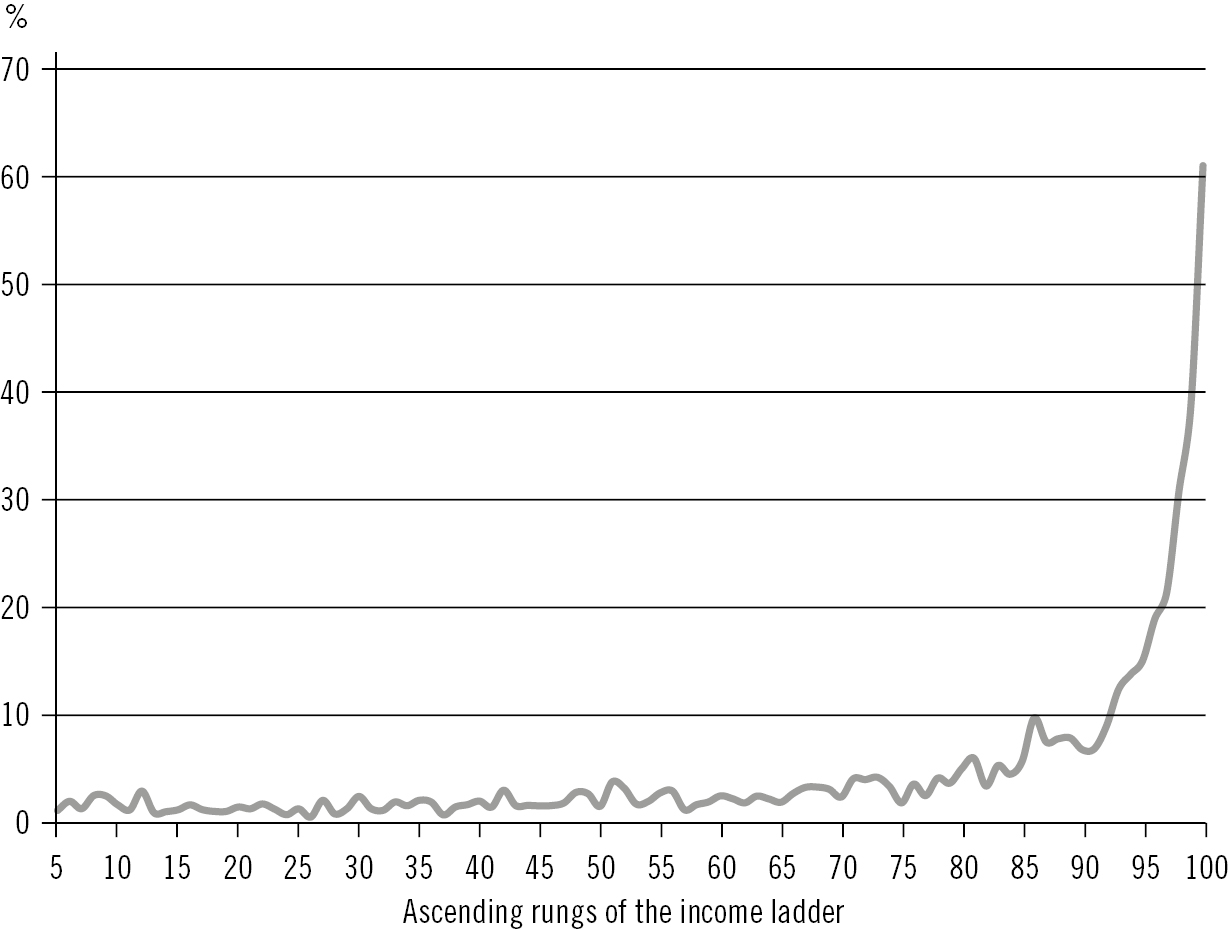

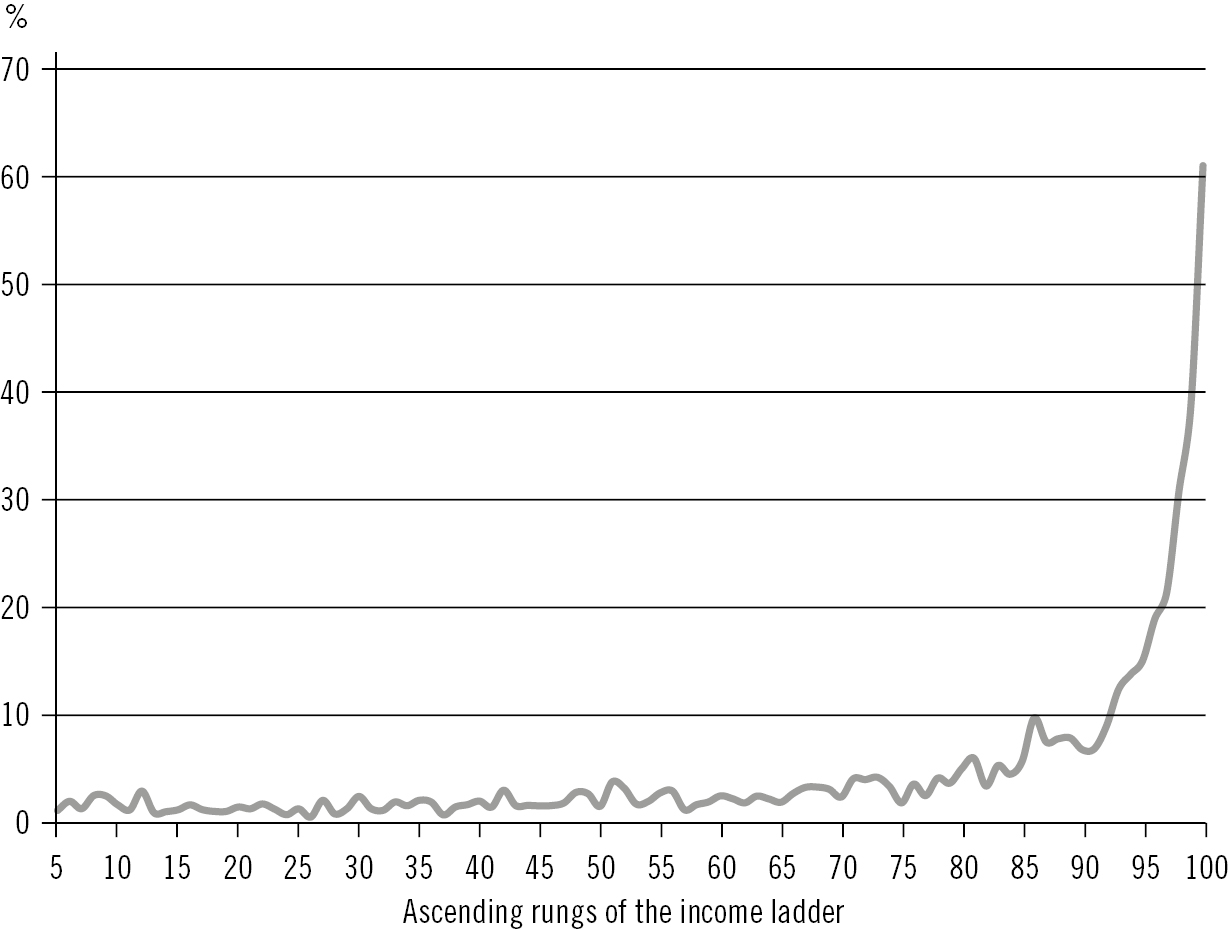

What particularly defines British private education as provided by prep (that is, preparatory) schools at the primary stage and public (that is, private) schools at the secondary is its extreme social). At every rung of the income ladder there are a small number of private school attenders; but it is only at the very top, above the 95th rung of the ladder where families have an income of 120,000 that there are appreciable numbers of private school children. At the 99th rung families with incomes upwards of 300,000 six out of every ten children are at private school.

FIGURE 1 Percentage in private school at each rung of the income ladder

Source: Data from Family Resources Survey; see Green, F., J. Anders, M. Henderson and G. Henseke (2017), Who Chooses Private Schooling in Britain and Why?, Centre for Research on Learning and Life Chances (LLAKES), London, Research Paper 62. The base population is all children aged fivefifteen living in private households in Great Britain, between 2001/2002 and 2015/2016. The income rungs are the percentiles of their families gross weekly income.

A glance at the annual fees, and even more so sixth forms, the fees are appreciably higher. In short, access to private schooling is, for the most part, available only to wealthy households. Indeed, the small number of income-poor families going private can only do so through other sources: typically, grandparents assets and/or endowment-supported bursaries from some of the richest schools. Overwhelmingly, pupils at private schools are rubbing shoulders with those from similarly well-off backgrounds.

They arrange things somewhat differently elsewhere: among affluent countries, Britains private school participation is especially exclusive to the rich. fee-paying schooling is confined to a handful of boarding schools with fees a fraction of their British equivalents, educating less than half a per cent of the population. Britains private school configuration is, in short, distinctive.

19972018: a brief, expensive history

And what, then, does Britain look like in the twenty-first century? As the millennium approaches, New Labour under Tony Blair (Fettes) sweeps to power. The Bank of England under Eddie George (Dulwich) gets independence. The chronicles of Hogwarts School begin. A nation grieves for Diana (West Heath); Charles (Gordonstoun) retrieves her body; her brother (Eton) tells it as it is. Martha Lane Fox (Oxford High) blows a dotcom bubble. Charlie Falconer (Glenalmond) masterminds the Millennium Dome. Will Young (Wellington) becomes the first Pop Idol. The Wires Jimmy McNulty (Eton) sorts out Baltimore. James Blunt (Harrow) releases the best-selling album of the decade. Northern Rock collapses under the chairmanship of Matt Ridley (Eton). Boris Johnson (Eton) enters City Hall in London. The CameronOsborne (EtonSt Pauls) axis takes over the country; Nick Clegg (Westminster) runs errands. Life staggers on in austerity Britain mark two. Jeremy Clarkson (Repton) cant stop revving up; Jeremy Paxman (Malvern) still has an attitude problem; Alexandra Shulman (St Pauls Girls) dictates fashion; Paul Dacre (University College School) makes Middle England ever more Mail-centric; Alan Rusbridger (Cranleigh) makes non-Middle England ever more Guardian-centric; judge Brian Leveson (Liverpool College) fails to nail the press barons; Justin Welby (Eton) becomes top mitre man; Frank Lampard (Brentwood) becomes a Blues legend; Joe Root (Worksop) takes guard; Henry Blofeld (Eton) spots a passing bus. The CameronOsborne axis sees off Labour, but not Boris + Nigel Farage (Dulwich) + Arron Banks (Crookham Court). Ed Balls (Nottingham High) takes to the dance floor. Theresa May (St Julianas) and Jeremy Corbyn (Castle House) face off. Prince George (Thomass Battersea) and Princess Charlotte (Willcocks) start school.

Lifes gilded path

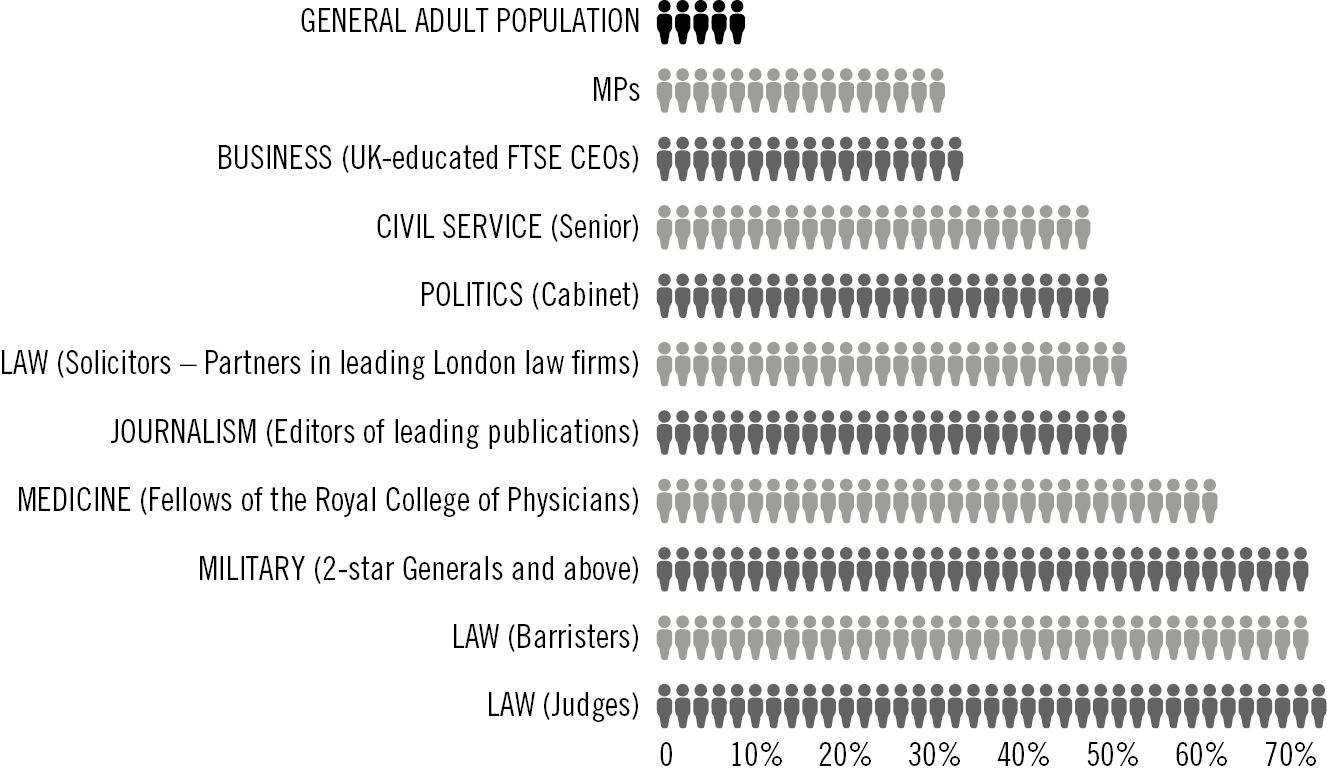

The statistics also tell a story. The fullest, most authoritative survey of the extent of the dominance of the privately educated in twenty-first-century Britain has been published by the Sutton

FIGURE 2 Percentage privately educated among the rich and powerful