Contents

It is becoming more and more obvious that it is not starvation, it is not microbes, it is not cancer, but man himself who is his greatest danger: because he has no adequate protection against psychic epidemics, which are infinitely more devastating in their effect than the greatest natural catastrophes.

C. G. Jung, Modern Man in Search of a Soul

It is only by obtaining some sort of insight into the psychology of crowds that it can be understood... how powerless they are to hold any opinions other than those which are imposed upon them.

Gustave Le Bon, The Crowd

As I write this in the early months of 2019, few would deny that the world around us is in many ways in a peculiarly odd and far from happy state. Wherever we look, there is scarcely a single country, society or continent which is not wracked by strains, stresses and divisions which even a decade ago would have been hard to imagine.

What, for instance, do all these familiar features of our time have in common?

1 The spectacular rise in our time of Islamic terrorism, extending its shadow over almost every continent, with its fanatical adherents so possessed by the rightness of their cause that it justifies them killing anyone who does not subscribe to it, and even themselves.

2 The rise of identity politics and the peculiar social and psychological pressure to conform with a whole range of views deemed to be politically correct, marked out in those caught up in it by their aggressive intolerance of anyone who or anything which differs from their own beliefs.

3 The omnipresent influence of social media, again too often marked out by intolerant abuse of other people and their views.

4 The belief that the greatest threat facing the planet is man-made global warming, from which it can only be saved by eliminating the use of the fossil fuels on which modern civilization was built and continues to rely. Again, this is marked out by a peculiar intolerance of anyone who fails to share that belief, or of any factual evidence which seems to challenge it.

5 The conspicuous alienation of so many governments and political elites from the people they rule over, giving rise to populist movements which can be scorned or ignored.

6 The unprecedentedly divided state of American politics in the age of President Trump, again marked out by the inability of either side to tolerate the views of the other.

7 The similarly divided and chaotic state of politics in the UK following its referendum on leaving the European Union, again marked out by the inability of the multiple factions to understand or tolerate any views which differ from their own.

8 The other strains emerging across the European Union itself, resulting from the belief driving its evolution for over 70 years, that Europes future must lie in integrating all its individual nations under a unique form of government such as the world had never seen before.

To these we could add countless other examples, from the fanatical intolerance of animal rights activists to the peculiarly unquestioning bias shown on these and many other issues by most of the mainstream Western media, most conspicuously led in Britain by the BBC.

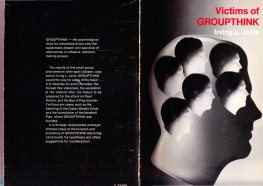

The purpose of this book is to provide the missing key to understanding much about these bewildering times that so many people have found increasingly alarming. We shall be looking at all these examples and more in the light of a remarkable thesis put forward in a book published more than 40 years ago by a professor of psychology at Yale University, Irving Janis.

Janiss field of study was the workings of collective human psychology, and specifically the way in which groups of people can behave when they are taken over by a kind of group mind. Others had written books about this kind of human herd behaviour before, such as Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds , by a Scottish journalist, Charles MacKay, in 1841. A rather more profound work was The Crowd , by a Frenchman, Gustave le Bon, in 1895. But what made Janiss The Victims of Groupthink (1972) quite different from these was that, as a disciplined scientific study, it showed for the first time how this kind of collective behaviour operates according to certain consistent and identifiable rules.

A group of people comes to be fixated on some belief or view of the world which seems hugely important to them. They are convinced that their opinion is so self-evidently right that no sensible person could disagree with it. Most telling of all, this leads them to treat all those who differ from their beliefs with a peculiar kind of contemptuous hostility.

When I first read Janiss book, one of my first thoughts was how well it helped to explain and illuminate so much that I had been writing about through most of my professional life. Again and again, I had found myself analysing instances of how groups of people had got carried away en masse by some powerfully beguiling idea which was not properly based on reality. It had invariably turned out to be rooted in some way in a kind of collective make-believe. And in each case, they had displayed a particular form of dismissive intolerance towards anyone who did not share their mind-set.

We are never more aware of groupthink at work than when we come up against people who hold an emphatic opinion on some controversial subject, but who, when questioned on it, turn out not really to have thought it through. They have not looked seriously at the facts or the evidence. They have simply taken their opinions or beliefs on trust, ready-made, from others. But the very fact that their opinions are not based on any real understanding of why they believe what they do only allows them to believe even more insistently and intolerantly that their views are right.

These are the victims of groupthink Janis was writing about all those years ago. Today they are around us more obviously than ever. We meet them socially, we hear and read them incessantly in the media, we see our politicians speaking in the clichs of groupthink all the time. The psychological condition from which they are suffering is contagious, extremely powerful and increasingly showing itself to be potentially very dangerous.

This book is about learning how to recognize the nature and power of groupthink in all its guises. But before we look at a wide range of examples, we need first to establish a more detailed picture of what Janiss analysis tells us about the rules governing the way groupthink works.

I use the term groupthink as a quick and easy way to refer to a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, when the members strivings for unanimity over-ride their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action.

Groupthink is a term of the same order as the words in the Newspeak vocabulary George Orwell presents in his dismaying 1984 a vocabulary with terms such as doublethink and crimethink. By putting groupthink with those Orwellian words, I realise that groupthink takes on an Orwellian connotation. The invidiousness is intentional: groupthink refers to a deterioration of mental efficiency, reality testing and moral judgment.

Irving Janis, Victims of Groupthink (1972)

Of course, we hear people casually using the word groupthink all over the place, usually to dismiss those with whose opinions they disagree. But in consciously adapting this word from George Orwell, Janis was the first person to show that there is a consistent structure to the way the concept operates, which is why his work deserves to be recognized as such a valuable contribution to science. Nevertheless, there is an obvious reason why his book published in 1972 (revised in 1982 as just Groupthink ) is not better known than it might be. This is that Janis based his theory only on a very specific and limited set of examples.