Also available from Bloomsbury

A Cultural History of Sexuality in the Classical World,

Mark Golden and Peter Toohey

Greek and Roman Sexualities: A Sourcebook, Jennifer Larson

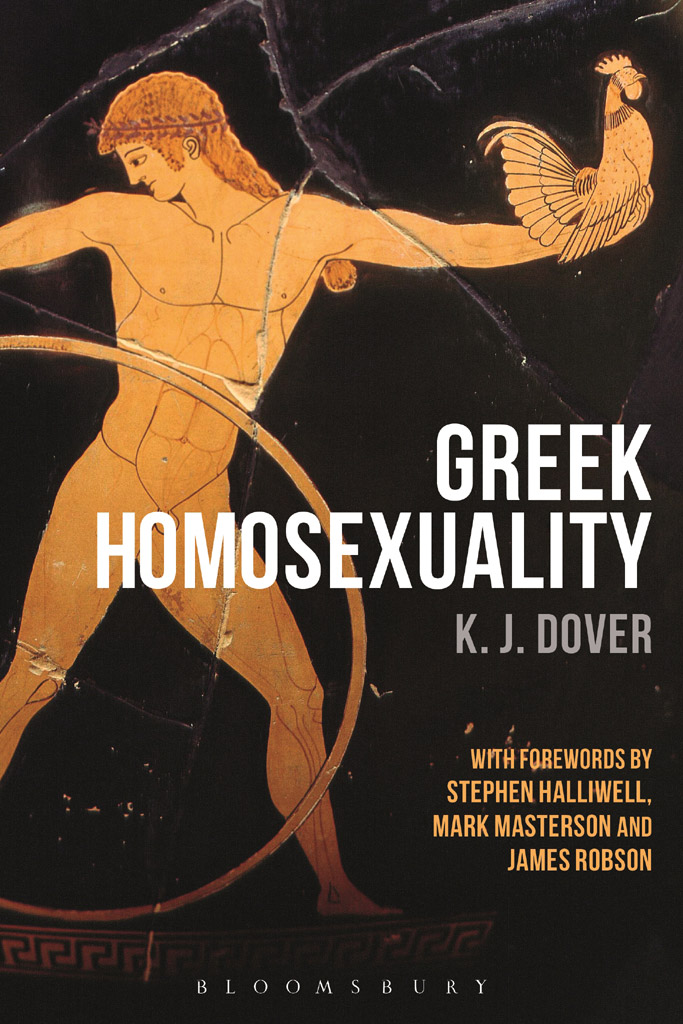

The publication of Kenneth Dovers Greek Homosexuality in 1978 was a landmark in the study of ancient Greek culture. Written by one of the twentieth centurys greatest Hellenists at the peak of his career (he had been knighted for services to scholarship in 1977 and became President of the British Academy in 1978 itself), it was the first work to treat Greek representations of homoerotic psychology and practice with the full panoply of historical and philological methods of analysis, as well as in a manner which adroitly synthesised the various forms of evidence (literary, iconographic, philosophical, mythological, religious) for the social phenomena in question. Few classical monographs have been translated, like this one, into a dozen languages, including Hungarian and Japanese.

But the books originality, combined with the highly charged nature of its subject-matter, made it inevitably a source of controversy from the outset. So much investigation of ancient sexuality has followed in its wake, and so much has changed (on the surface at least) in general sexual mores and discourse in the intervening years, that one needs to remind oneself (if ones memory goes back that far) just how momentous the publication of Greek Homosexuality seemed in the late 1970s. For some, it was an intellectually liberating event: Dover had shown that it was possible and productive to discuss all aspects of the topic, from the level of anatomical detail to that of philosophical theory, without inhibitions or reservations, indeed with a sometimes clinical explicitness which Dover thought a necessary counterweight to euphemism (or worse), both ancient and modern. To others, however, the book was a cause of dismay even somewhat threatening to the decorum of the status quo precisely in virtue of its linguistic and imaginative candour, tokens of a conspicuous determination to treat its materials as raising legitimate, important, and fascinating questions about a remarkable human culture.

together with the translation of that acceptance into a distinctive nexus of social, artistic, and literary forms of expression. Little sign here, then, of anything like a will to uncover something hidden or repressed within the Greeks self-understanding in this domain of behaviour.

Dovers first awareness of the need for a rigorous scholarly exploration of Greek homosexuality occurred around 1954 when, as a Fellow of Balliol College, he lectured for the Oxford Classics syllabus on the collection of elegiac poems attributed to the sixth-century B.C . poet Theognis. For example, as early as 1955, the year in which he left Oxford to become Professor of Greek at the University of St. Andrews, Dover was planning an edition of Aristophanes Clouds (it would eventually be published in 1968), a play which contains several passages involving humorous reference to homosexual desire, not least in relation to perceptions of the (partially) naked bodies of young males in educational and athletic contexts.

A decisive juncture occurred in 1962 when Dover started to teach Platos Symposium, a dialogue which had long possessed a special status within idealising accounts of Greek love from Ficino to Oscar Wilde (and beyond). Dovers work on the Symposium led him to reconsider its salient elements of homoeroticism and prompted his thinking to move in directions which would sharply diverge from those older tendencies towards idealisation. When he subsequently received an invitation to deliver a series of lectures at University College London in February 1964, he chose the Symposium as his theme and called one of the lectures Eros and Nomos: roughly speaking, sexual desire and social norms.

That lecture, which initially focuses on one particular speech (Pausaniass) from the Symposium, attempts to bring a new sophistication to bear on the interpretation of ancient sexuality, in part by taking account of modern sociological findings (it draws on the Kinsey reports interestingly, not cited in Greek Homosexuality itself) about the unstable relationship between preconceptions and reality in sexual behaviour. But Dovers reading of Pausaniass speech exhibits tensions which would recur in the book too. Despite his aversion to what he saw as Platos other-worldly values and remoteness from material reality, Dover thought he could sidestep Platos own idealistic distortions and extract nuggets of quasi-sociological information from Pausaniass speech. He wanted specifically to place great weight on Pausaniass depiction of the double standard by which Athenian society supposedly encouraged male lovers in their pursuit of adolescent male beloveds, yet

Lively reactions to the publication of Eros and Nomos, later in 1964, triggered a decision on Dovers part to devote a whole book to Greek homosexuality. Although other projects postponed implementation of that decision, it is striking that aspects of the subject made a significant appearance in several books on which Dover was working, more or less simultaneously, between the mid-1960s and mid-1970s: his edition of Clouds (1968), already mentioned above; a student edition of selected poems of Theocritus (1971), a poet whose bucolic world embeds homosexual motifs in scenes of various sorts, among them exchanges of risqu gossip and abuse between herdsmen; Aristophanic Comedy (1972), which reiterates some of the views advanced in the edition of Clouds; and Greek Popular Morality (1974), which provides much of the armature of Dovers broader understanding of Greek values and mentalities (it is cited frequently in Greek Homosexuality) as well as supplying its own prcis of Athenian attitudes to homosexuality. The extent to which Dovers thoughts on the subject were coalescing during this period is demonstrated by an article

The homosexuality project itself finally took centre stage for some five years from 1973 onwards, including the first part of Dovers presidency of Corpus Christi College Oxford (1976-86). He now occupied himself intensively with the book, undertaking a systematic trawl of the evidence of vase-painting partly through publications, partly by autopsy in museum collections to supplement the literary and rhetorical texts on which he had long been an expert. At one point, in 1972, he had contemplated writing the book in collaboration with the Hungarian-French anthropologist and psychoanalyst George Devereux, whom he had known since 1964. Dover had a cast of mind which, despite an almost unwavering adherence to empiricist and rational standards of argument, had always accommodated some personal attraction to Freudian ideas; he was reading Freud seriously even as a teenager. But that influence cannot be shown to have affected the substance of the work, which steers largely clear of the kind of speculative, a priori psychological theorising to which Devereux was addicted.

but typically coexisted or alternated with heterosexual desire in the same individual as part of the overall operations of ers, i.e. passionate and obsessive desire for a particular person thus making the cultural contours of the subject very uneven and hard to map. And in any case, he realised that establishing the truth about the intimate facts of any particular relationship was virtually out of the question: he distanced himself from those who smugly thought they could guess what must actually have happened between, for example, Socrates and Alcibiades.

But despite those caveats and gestures of caution, Dover deliberately organised most of his book around an attempt to build up a detailed picture of the attitudes and protocols which shaped one particularly important category of same-sex relationship, namely the socially ritualised association between an adult (though sometimes still