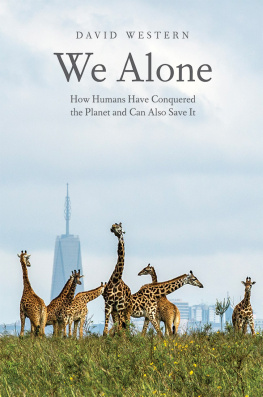

We Alone

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Henry Weldon Barnes of the Class of 1882, Yale College.

Copyright 2020 by David Western.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in ITC Galliard Pro and Gotham type by IDS Infotech, Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020935060

ISBN 978-0-300-25116-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All photographs are from the authors collection unless otherwise noted.

To Shirley, Carissa, and Guy,

and the communities that have done so much to

conserve wildlife

Contents

Preface

We stand at a pivotal point in human history. In our rise from small, scattered Neolithic communities living precariously, we have become so supremely dominant as to reshape nature, change the course of evolution, and engineer a new geological age, the Anthropocene. In the process we have created a global economy that has narrowed our food webs and stretched our supply chains to the point that we can no longer sense or contain our planetary impact.

Belatedly, climate warming has risen to the top of the international agenda as hotter summers, colder winters, stronger hurricanes, torrential floods, searing droughts, and rising sea levels impinge on our daily lives. Trapped between a receding industrial age powered by toxic and dwindling fossil fuels and the fourth industrial revolution and circular economy promising hope of a greener planet and sustainable lifestyles, we face a tragedy of the global commons for lack of action.

Prescriptions for a sustainable future range from strong central government control to trusting in the invisible hand of free markets and reliance on rational choices. Yet neither Big Government nor Free Markets have yet solved the ultimate human challenge of living within planetary limits.

In We Alone I look for answers by delving into how we rose from a lowly savanna primate to conquer the Earth and examine how successful socie-ties avoided the pitfalls of overuse and social breakdown. My exploration is partly a personal voyage tracing my evolution from hunter to conservationist, highlighting insights Ive gleaned from observing communities: from the Maasai surviving droughts to Californians up against intensifying droughts and wildfires caused by global warming. I also draw on scientific discoveries over the last half century to show how we humans are far from being constrained by the selfish gene and limited by local ecology; instead our success lies in cooperation and cultural institutions that enable us to create novel economies and lifestyles that defy the biological imperative to reproduce to the limits of food supply.

I argue that our global conquest lay in breaking biological barriers, domesticating the selfish gene, and curbing the downsides of our actions for larger common gains. The more ecologically emancipated we became, the greater grew our ability to shift beyond conserving food and water for survival to saving whales, art, music, and cultural traditions, based on our newfound knowledge and sensibilities. Conserving other species lifts us to the highest plane of altruism, beyond kinship, tribe, and economic self-interest.

Our future well-being depends on our unique capacity for cooperation, foresight, and planning as well as on new technologies and green economies, rather than in using a vanishing Pleistocene Age as a template. No less than in the past, our success hinges on using our emotions, morality, and expanded empathy to create the world we wish for rather than the polluted and degraded planet we have inherited.

We Alone takes up where Aldo Leopolds A Sand County Almanac leaves off by showing that we can scale up from husbanding the land to sustaining the planet within boundary limits. Neither the end-of-nature pessimists nor rational optimists offer solutions for cleaning up the global problems we have created. Our future lies in the collective actions of billions of citizens, not in philosophical debates and scientific prescriptions.

We Alone is written for a popular audience, but it is also intended to appeal to students looking for answers to who we are and how we can become good custodians of the global commons.

We Alone

Introduction: Confronting the Human Age

This book could be a depressing one about the end of our planet because of human folly. It isnt. Nor is it about wildlife and conservation in Africa, although I lay the foundation for a far larger exploration of our past and future in southern Kenya, where I have worked for the past five decades. Instead, this book is about another savanna species altogether: us.

In We Alone I look at conservation from the dual perspective of our ancient savanna origins, which shaped our nature, and the new global age in which we are reshaping nature. What is so unique about our species as to have propelled us from a small-time savanna primate to a globally superdominant species capable of changing nature, ourselves, and our planet? What lessons do cultures that beat the ecological odds and thrived for millennia have to offer our global society, now knocking against planetary limits?

My exploration began with the role conservation played in the survival of Maasai pastoralists battling droughts and competing with wildlife. If they had to struggle so hard to combat the elements, how did our early ancestors, the puniest of the great apes, outcompete all other species and rise to global supremacy? My interests grew with visits to other traditional societies, among them !Kung hunter-gatherers of the Kalahari, Mbuti pygmies of the Ituri Forest, Konso and Gammo farmers of the Ethiopian Highlands, Bedouins in the Middle East and Sahara, Andean farmers of Peru, and yak herders of the Tibetan Plateau.

The exploration led me on a yet deeper quest into the meaning of conservation itself and how it evolved from its roots in survival and necessity to encompass the bewildering variety of things we conserve todayfrom whales, lions, and wolves to historical buildings, art, music, and above all the diversity of life itself. What, if anything, do these varied strands of conservation have in common?

Over the course of barely two centuries, subsistence herding and farming societies tied to rainfall and the seasons have coalesced into a global society and interwoven economy. Amboseli, situated beneath the rising mass of Kilimanjaro in Kenya, gives a snapshot of the last vestiges of the Neolithic Age merging into the Anthropocenea world in transition from nature shaping our livelihoods and culture to one in which we are molding nature for our own safety, comfort, and enjoymentoften with unknown and unintended consequences. The Anthropocene marks an extraordinary juncture in human history when thousands of years of differentiation in cultures, lifestyles, and languages are converging into a single entangled community.

In the early 1970s my first visit to California, half a world away from Amboseli, jolted all my expectations of Americas third largest metropolis, Los Angeles. My taxi from the airport ground to a standstill, blocked by an endless stream of traffic filling the Santa Monica Freeway bumper to bumper in both directions. An acrid blanket of urban smog stung my eyes, burned my lungs, and hid the iconic Hollywood sign up in the hills. What good do riches do, I wondered, if the price is clogged freeways and congested lungs? On university campuses where I had come to lecture on African wildlife, I was struck by the irony of Americans interest in African animalsmany traveling to Africa to film lions, elephants, and the great Serengeti wildebeest migrationswhile they did little to save their own: the bald eagle, the national symbol; the last of the countrys wolves; the endangered grizzly; and the plains bison.

Next page