INTRODUCTION

T HE Master of Game is the oldest as well as the most important work on the chase in the English language that has come down to us from the Middle Ages.

Written between the years 1406 and 1413 by Edward III.s grandson Edward, second Duke of York, our author will be known to every reader of Shakespeares Richard II., for he is no other than the arch traitor Duke of Aumarle, previously Earl of Rutland, who, according to some historians, after having been an accomplice in the murder of his uncle Gloucester, carried in his own hand on a pole the head of his brother-in-law. The student of history, on the other hand, cannot forget that this turbulent Plantagenet was the gallant leader of Englands vanguard at Agincourt, where he was one of the great nobles who purchased with their lives what was probably the most glorious victory ever vouchsafed to English arms.

He tells us in his Prologue, in which he dedicates his litel symple book to Henry, eldest son of his cousin Henry IV., Kyng of Jngelond and of Fraunce, that he is the Master of Game at the latters court.

Let it at once be said that the greater part of the book before us is not the original work of Edward of York, but a careful and almost literal translation from what is indisputably the most famous hunting book of all times, i.e. Count Gaston de Foixs Livre de Chasse, or, as author and book are often called, Gaston Phbus, so named because the author, who was a kinsman of the Plantagenets, and who reigned over two principalities in southern France and northern Spain, was renowned for his manly beauty and golden hair. It is he of whom Froissart has to tell us so much that is quaint and interesting in his inimitable chronicle. La Chasse, as Gaston de Foix tells us in his preface, was commenced on May 1, 1387, and as he came to his end on a bear hunt not much more than four years later, it is very likely that his youthful Plantagenet kinsman, our author, often met him during his prolonged residence in Aquitaine, of which, later on, he became the Governor.

Fortunately for us, the enforced leisure which the Duke of York enjoyed while imprisoned in Pevensey Castle for his traitorous connection with the plots of his sister to assassinate the King and to carry off their two young kinsmen, the Morti mers, the elder of whom was the heir presumptive to the throne, was of sufficient length to permit him not only to translate La Chasse but to add five original chapters dealing with English hunting.

These chapters, as well as the numerous interpolations made by the translator, are all of the first importance to the student of venery, for they emphasise the changesas yet but very trifling onesthat had been introduced into Britain in the three hundred and two score years that had intervened since the Conquest, when the French language and French hunting customs became established on English soil. To enable the reader to see at a glance which parts of the Master of Game are original, these are printed in italics.

The text, of which a modern rendering is here given, is taken from the best of the existing nineteen MSS. of the Master of Game, viz. the Cottonian MS. Vespasian B. XII., in the British Museum, dating from about 1420. The quaint English of Chaucers day, with its archaic contractions, puzzling orthography, and long, obsolete technical terms in this MS. are not always as easy to read as those who only wish to get a general insight into the contents of the Master of Game might wish. It was a difficult question to decide to what extent this text should be modernised. If translated completely into twentieth century English a great part of the charm and interest of the original would be lost. For this reason many of the old terms of venery and the construction of sentences have been retained where possible, so that the general reader will be able to appreciate the feeling of the old work without being unduly puzzled. In a few cases where, through the omission of words, the sense was left undetermined, it has been made clear after carefully consulting other English MSS. and the French parent work.

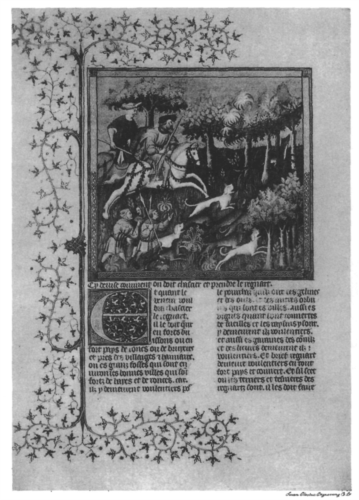

It seemed very desirable to elucidate the textual description of hunting by the reproduction of good contemporary illuminations, but unfortunately English art had not at that period reached the high state of perfection which French art had attained. As a matter of fact, only two of the nineteen English MSS. contain these pictorial aids, and they are of very inferior artistic merit. The French MSS. of La Chasse, on the other hand, are in several cases exquisitely illuminated, and MS. f. fr. 616, which is the copy from which our reproductionsmuch reduced in size, alas!are made, is not only the best of them, but is one of the most precious treasures of the Bibliothque Nationale in Paris. These superb miniatures are unquestionably some of the finest handiwork of French miniaturists at a period when they occupied the first rank in the world of art.

The editors have added a short Appendix, eluci dating ancient hunting customs and terms of the chase. Ancient terms of venery often baffle every attempt of the student who is not intimately acquainted with the French and German literature of hunting. On one occasion I appealed in vain to Professor Max Mller and to the learned Editor of the Oxford Dictionary. I regret to say that I know nothing about these words, wrote Dr. Murray; terms of the chase are among the most difficult of words, and their investigation demands a great deal of philological and antiquarian research. There is little doubt that but for this difficulty the Master of Game would long ago have emerged from its seclusion of almost five hundred years. It is hoped that our notes will assist the reader to enjoy this hitherto neglected classic of English sport. Singularly enough, as one is almost ashamed to have to acknowledge, foreign students, particularly Germans, have paid far more attention to the Master of Game than English students have, and there are few manuscripts of any importance about which English writers have made so many mistakes. This is all the more curious considering the precise information to the contrary so easily accessible on the shelves of the British Museum. All English writers with a single exception (Thomas Wright) who have dealt with our book have attributed it persistently to a wrong man and a wrong period. This has been going on for more than a century; for it was the learned, but by no means always accurate, Joseph Strutt who first thrust upon the world, in his often quoted Sports and Pastimes of the English People, certain misleading blunders concerning our work and its author. Blaine, coming next, adding thereto, was followed little more than a decade later by Cecil, author of an equally much quoted book, Records of the Chase. In it, when speaking of the Master of Game, he says that he has no doubt that it is the production of Edmund de Langley, thus ascribing it to the father instead of to the son. Following Cecils untrustworthy lead, Jesse, Lord Wilton, Vero Shaw, Dalziel, Wynn, the author of the chapter on old hunting in the Badminton Library volume on Hunting, and many other writers copied blindly these mistakes.

![of Norwich Edward The master of game : [the oldest English book on hunting]](/uploads/posts/book/301095/thumbs/of-norwich-edward-the-master-of-game-the.jpg)