This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1925 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

WELLINGTON: THE CROSSING OF THE GAVES AND THE BATTLE OF ORTHEZ

BY

MAJOR-GENERAL F. C. BEATSON CB

Higher THE GAVE DE PAU AT BERENX, LOOKING DOWN STREAM FROM THE ROAD BRIDGE.

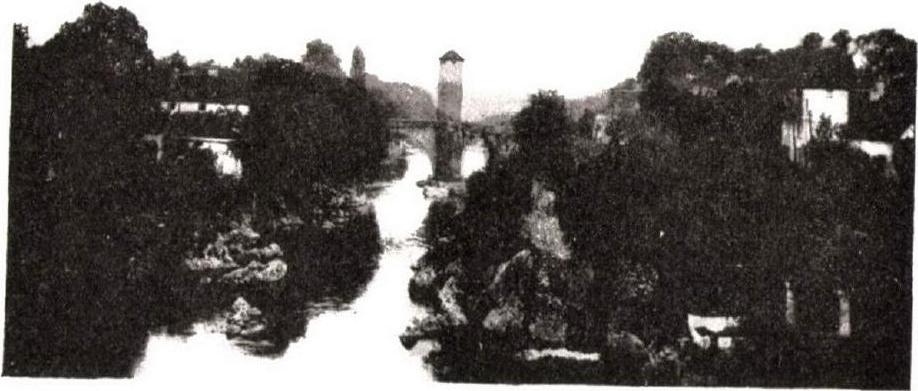

Lower .THE GAVE DE PAU AND THE OLD BRIDGE OF ORTHEZ, LOOKING DOWN STREAM FROM THE NEW BRIDGE.

PREFACE

IN this book an attempt is made to show how the greatest of modern British Generals planned and carried out the first stages in the execution of the task set him by his Government, namely, to make a further advance into French territory, and thereby render efficient cooperation to the armies of the other Great Powers then about to invade Northern and Eastern France.

The distance between the two spheres of action was too great to permit the hope of active cooperation between the armies under Wellington and those of Austria, Prussia and Russia. This Wellington recognized, though it does not appear to have been so clearly realized at the headquarters of the allied sovereigns. The cooperation had to be indirect and be worked by preventing Napoleon from calling to himself the large force of veteran soldiers he still had in the south, by pushing back those opposed to the allied armies under Wellington, and so bringing under the latters control a large and wealthy area of Southern France, thereby lessening the Emperors prestige and imposing on him the loss of considerable resources in men and money, and opening also a field for action against him by the supporters of the Bourbon party.

When considering the shaping of a plan of action political considerations, finance, the forces available and those of the enemy, the nature of the country about to be operated over, its physical features and its communications, the supply of the army, the weather, the character of the opposing commander, his probable object and the moral of his troops, together with local circumstances at the moment which may tend to aid or hamper the enterprise, have all to be considered. It has been felt necessary, therefore, to consider as briefly as possible all or most of these factors as affecting both sides: so that the reader may have sufficient information of what in the circumstances stood for or against the contending leaders.

On a day like this when our thoughts are full of the heroic deeds performed seven years ago by our soldiers, it is perhaps well also not to forget those of our forebears. In February, 1814, that little Peninsular army, the finest of its day, was in the full flower of its moral, its experience, its steadiness, its marksmanship which its opponents could not bear or challenge, full of confidence in itself and in its leader, wayward sometimes and needing to be held with a tight rein, but never dismayed; it was the prototype of that army, small and termed contemptible, which in August, 1914, slipped away over the sea, saved France and Europe, lost itself but never its glory.

Above it stands the figure of its Great Commander, he who, by his genius for war, his loyalty, his steadfast confidence, absolute truthfulness, patience and devotion to duty and his country, had led it for five years through good and evil days from the shores of Portugal across Spain and the Pyrenees and over the frontier of France. With that little army, says Colonel Charras, the French historian of Waterloo, he did great things, and that army was his work. He will remain one of the grandest military figures of this (the nineteenth) century.

But it may be said, What is the use of reading or of soldiers studying operations which took place a hundred and eleven years ago. Science and invention have changed the world since then; the lessons they may teach us will be of no use today. But is the statement quite true? Let us see what the great master of modern war says. Generals in Chief must be guided by their own experience or genius. Tactics, evolutions, the art of the engineer and artilleryman may be learnt in treatises, but that of strategy is only to be acquired by experience and by studying the campaigns of all the great captains. Read again and again the campaigns of Hannibal, Caesar, Gustavus Adolphus, Turenne, Eugene and Frederick. Model yourself upon them. This is the only way of acquiring the secret of the art of war. {1}

And what says his disciple, the great soldier of today, Marshal of France and of England? He declares that even after the latest campaigns, though war has at its disposal today means more powerful, more numerous and more delicate, the same laws as of old must be obeyed. Forms evolve, directing principles remain unchanged.

A great teacher and writer to whom the British army and empire owe much, the late Lieutenant Colonel G. F. R. Henderson, often declared that for British officers the campaigns of Wellington have a special and practical value as regards the application of strategical principles, because he considered the British officer will more often than not be called on to campaign under conditions not unlike those in the Peninsula, such as dependence on sea power, association with allies entailing semi-diplomatic functions and always patience and tact, and sometimes having to improvise administrative services with scanty means and inexperienced officials.

But for Colonel Hendersons untimely death we should now have a real military life of Wellington. This is not an attempt in any way to fill the gap: but merely to give an example of how that general applied his strategical skill with a highly perfected machine.