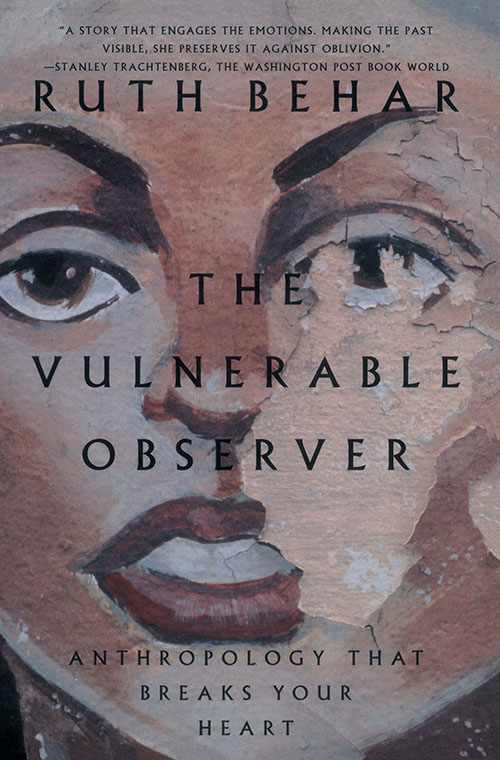

OTHER BOOKS BY RUTH BEHAR

The Presence of the Past in a Spanish Village:

Santa Mara del Monte

Translated Woman:

Crossing the Border with Esperanzas Story

ANTHOLOGIES EDITED BY RUTH BEHAR

Bridges to Cuba/Puentes a Cuba

Women Writing Culture

(with Deborah A. Gordon)

for

DEB CHASMAN

my vulnerable editor

Viajero

Yo soy como el viajero

que llega a un puerto y no lo espera nadie;

Soy el viajero tmido que pasa

entre abrazos ajenos y sonrisas

que no son para l...

Como el viajero solo

que se alza el cuello del abrigo

en el gran muelle fro...

Traveler

I am like the traveler

who reaches the port and no one awaits him;

I am the timid traveler who walks

among strangers embracing and smiles

not meant for him...

Like the lone traveler

who raises his overcoat collar

on the great, cold wharf...

Dulce Mara Loynaz

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The essays in this book were written between 1987 and 1996. During these years my spirit and my writing have been nurtured by friends and colleagues in many fields. I am especially grateful for the faith given me by Ester Shapiro Rok, who encouraged me to believe that these essays might be creative writing and inspired me with her own thinking and writing about grief. Mara de los Angeles Torres always keeps me honest about Cuba, gently debriefing me on so many occasions. To Deborah Gordon I owe some of the most profound insights I have about myself as an anthropologist. Alan West has taught me to be a better poet. My essay on The Girl in the Cast would not have seen the light of day without the support and knowledge of Gelya Frank, Marianne Gullestad, Sandra Cisneros, Joanne Leonard, Susan Gelman, and Bruce Mannheim. I have been fortunate over the years to have James Fernandez, Jos Limn, Renato Rosaldo, and Victor Perera as caring mentors. Teofilo Ruiz and Scarlett Freund gave me absolutely essential comments, as only old friends can give, just before I let this book go. To all my deepest thanks.

My debt to those who allowed me to enter into their lives, knowing I would write about them, will never be fully repaid. I cannot, ever, make myself vulnerable enough.

I have been blessed with generous fellowship support from the MacArthur Foundation, the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation, the Lucius Littauer Foundation, the Council for International Exchange of Scholars, and most recently from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. At the University of Michigan I received grants from the International Institute, the Office of the Vice President for Research, and the Rackham School of Graduate Studies. This book was completed during a joyful period as a Rockefeller Residence Fellow at the Cuban Research Institute of Florida International University.

To my husband, David Frye, and my dear son, Gabriel, my thanks for their love and patience and for sleeping soundly while I wrote late into the night. And a special thank-you to Gabriel, who is teaching me so much with his own great big heart.

Deb Chasman, my editor at Beacon Press, had an inspired vision of how this book would tell its story. To la editora suprema, I dedicate this book, con el corazn en la mano.

Miami Beach

April, 1996

CHAPTER 1

The Vulnerable Observer

It is customary to call books about human beings either toughminded or tenderminded. My own is neither and both, in that it strives for objectivity about that tendermindedness without which no realistic behavioral science is possible.

George Devereux, From Anxiety to Method

I N 1985 an avalanche in Colombia buried an entire village in mud. Isabel Allende, watching the tragedy on television, wanted to express the desperation she felt as she helplessly observed so many people being swallowed by the earth. In her short story Of Clay We Are Created, Allende writes about Omaira Snchez, a thirteen-year-old girl who became the focus of obsessive media attention. News-hungry photographers, journalists, and television camera people, who could do nothing to save the girls life, descended upon her as she lay trapped in the mud, fixing their curious and useless eyes on her suffering. Amid that horrid audience of onlookers, which included Allende herself watching the cruel show on the screen, she places the photographer Rolf Cari. He too has been looking, gazing, reporting, taking pictures. Then something snaps in him. He can no longer bear to watch silently from behind the camera. He will not document tragedy as an innocent bystander. Crouching down in the mud, Rolf Cari throws aside his camera and flings his arms around Omaira Snchez as her heart and lungs collapse.

The vulnerable observer par excellence, Rolf Cari incarnates the central dilemma of all efforts at witnessing. In the midst of a massacre, in the face of torture, in the eye of a hurricane, in the aftermath of an earthquake, or even, say, when horror looms apparently more gently in memories that wont recede and so come pouring forth in the late-night quiet of a kitchen, as a storyteller opens her heart to a story listener, recounting hurts that cut deep and raw into the gullies of the self, do you, the observer, stay behind the lens of the camera, switch on the tape recorder, keep pen in hand? Are there limitsof respect, piety, pathosthat should not be crossed, even to leave a record? But if you cant stop the horror, shouldnt you at least document it?

Allende assumed that once her story was published, Omaira would disappear from her life. But in Paula, her moving memoir of her daughters sudden and rapid death from porphyria, she finds herself returning to Omairas story, which has acquired the eerie power of fiction that foretells the future. This time, Allende is painfully close to tragedy, no television screen acting as buffer. Like Rolf Cari, she must get down in the mud with her daughter, who has fallen into a coma, her gaze focused beyond the horizon where death begins. Sitting at the bedside of Paula, a Sleeping Beauty who will never awaken, Allende, with pen in hand, gives up the possibility of imagining other worlds through fiction. Surrendering to the intractableness of reality, she feels herself setting forth on an irreversible voyage through a long tunnel; I cant see an exit but I know there must be one. I cant go back, only continue to go forward, step by step, to the end.

F OR ME, anthropology is about embarking on just such a voyage through a long tunnel. Always, as an anthropologist, you go elsewhere, but the voyage is never simply about making a trip to a Spanish village of thick-walled adobe houses in the Cantabrian Mountains, or a garden apartment in Detroit where the planes circle despondently overhead, or a port city of cracking pink columns and impossible hopes known as La Habana, where they tell me I was born. Loss, mourning, the longing for memory, the desire to enter into the world around you and having no idea how to do it, the fear of observing too coldly or too distractedly or too raggedly, the rage of cowardice, the insight that is always arriving late, as defiant hindsight, a sense of the utter uselessness of writing anything and yet the burning desire to write something, are the stopping places along the way. At the end of the voyage, if you are lucky, you catch a glimpse of a lighthouse, and you are grateful. Life, after all, is bountiful.