1 Introduction

German, since these facts have given rise to traditional accounts for the phenomenon of remnant movement.

2 Remnant movement and the Proper Binding Condition (Saito 1992)

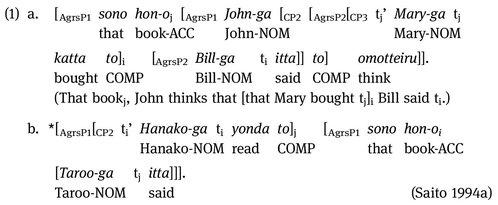

Japanese shows certain asymmetries in the scrambling of categories which contain the trace of a scrambled element. In the well-formed example (1a), the embedded CP3 that Mary bought that book has been adjoined to the AgrsP2 Bill said ..., and the object sono hon-o of the scrambled clause CP3 has undergone long scrambling to the matrix AgrsP1. In this configuration, the trace of the long-scrambled object is bound by its antecedent. In the ungrammatical example (1b), the object of the embedded clause CP2 has undergone long scrambling to the matrix AgrsP1 (Taroo said ...), followed by short scramling of CP2 itself.

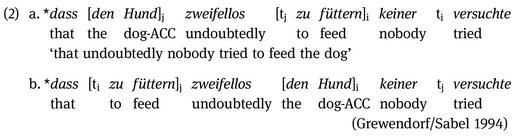

In German, the counterparts of the Japanese examples are both ungrammatical. In other words, scrambling of an XP out of a (short-)scrambled category is impossible in German irrespective of whether or not the scrambled XP binds its trace.

Saito (1992) accounts for the asymmetry observed in Japanese in terms of the Proper Binding Condition (PBC). Since scrambling can be freely undone at LF, PBC is assumed to not only apply at LF but also in the overt syntax.

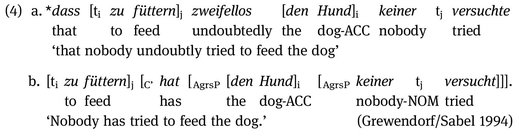

There are several empirical problems with an account in terms of PBC. The first problem has to do with the contrast between remnant scrambling and remnant topicalization in German. As can be seen from example (4a), a category XP from which scrambling has taken place cannot be followed by scrambling of the remnant to a position outside of the c-command domain of XP. However, as shown by (4b), topicalization of the remnant to SpecCP is well-formed even though the trace of the scrambled XP is no longer bound.

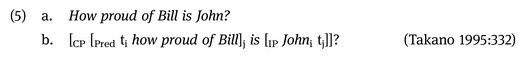

Another problem has been pointed out by Takano (1995). It concerns the combination of A-movement and remnant wh-movement. Given the VP-internal Subject Hypothesis, predicate fronting in (5) illustrates remnant wh-movement with an unbound A-trace (5b), which should be ungrammatical if the PBC holds in overt syntax.

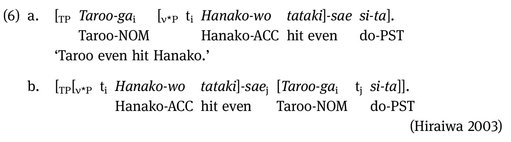

The third problem has to do with subject raising constructions in Japanese. As pointed out by Hiraiwa (2003), in Japanese subject raising constructions, the constituent from which subject raising takes place (v*P) can undergo scrambling. (6) shows that A-movement of the embedded subject Taroo-ga can be followed by scrambling of the remnant v*P. The result is well-formed although PCB is violated in the overt syntax.

3 Remnant movement and the Condition ofUnambiguous Domination (Mller 1996, 1998)

Rather than relying on the PCB, Mller (1996, 1998) has suggested to account for the ungrammaticality of (1b) and (2b) in terms of what he calls the Condition of Unambiguous Domination. According to this condition, remnant XPs are not allowed to undergo a certain type of movement if the antecedent of the unbound trace has undergone the same type of movement:

The various types of movement are taken to be scrambling, topicalization, wh-movement, A-movement. The Condition of Unambiguous Domination provides Mller with a simple account for the contrast between remnant scrambling and remnant topicalization in German, i.e. the contrast between (4a) and (4b). Since scrambling in German is adjunction and thus constitutes an instance of A-movement (Grewendorf/Sabel 1999), the trace of the scrambled element in example (4b) is dominated by a category which has itself undergone scrambling. This configuration violates (7). As far as the well-formed example (4b) is concerned, Mller points out that unlike the scrambled remnant in (4a), the remnant in (4b) has undergone topicalization so that in this case, the trace of the scrambled element is not dominated by an element which has undergone the same kind of movement. Condition (7) is therefore not violated.

Condition (7) also accounts for the ungrammaticality of the German example (2a). Since scrambling in German is without exception adjunction, the trace of the scrambled element in (2a) is dominated by a category which has itself undergone scrambling.

A problem arises with ungrammatical remnant scrambling in the A-movement in Japanese. Consequently, two different kinds of movement are involved so that condition (7) would be satisfied, contrary to fact. Note that this problem cannot be avoided by claiming that both kinds of scrambling belong to the same movement type (adjunction), since in that case example (1a) would be predicted to be ungrammatical, again contrary to fact.

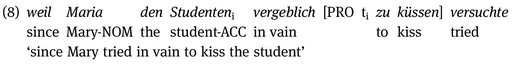

A similar empirical problem arises from German control facts. As is well-known, German permits long scrambling out of subject control infinitives embedded under certain control verbs:

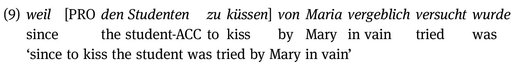

Since the adverbial vergeblich (in vain) in (8) can only modify the matrix verb, the embedded object den Studenten (the student) must have undergone long scrambling into the matrix clause. Furthermore, the control verb can be passivized with the infinitival object undergoing A-movement to the subject position, as in (9).

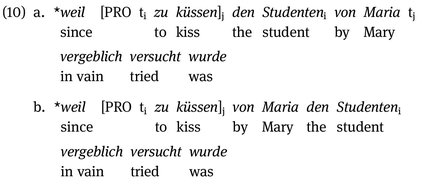

If we now combine long scrambling out of the infinitival object with A-movement of the latter, the Condition of Unambiguous Domination would predict the result to be well-formed, since two different kinds of movement are involved. However, as can be seen from the examples in (10), the result is ungrammatical:

4 Remnant movement and the Proper BindingCondition as a constraint on Merge(Saito 2002)

Saito (2002) offers a new account of the remnant movement problem by restating the PBC as a constraint on Merge:

He considers a constituent incomplete if it contains only part of a chain, e.g. a trace but not its antecedent. According to condition (11), the remnant category in (1b) is prevented from being merged. Condition (11) is thus taken to explain the ungrammaticality of scrambling a remnant constituent which contains an unbound trace.