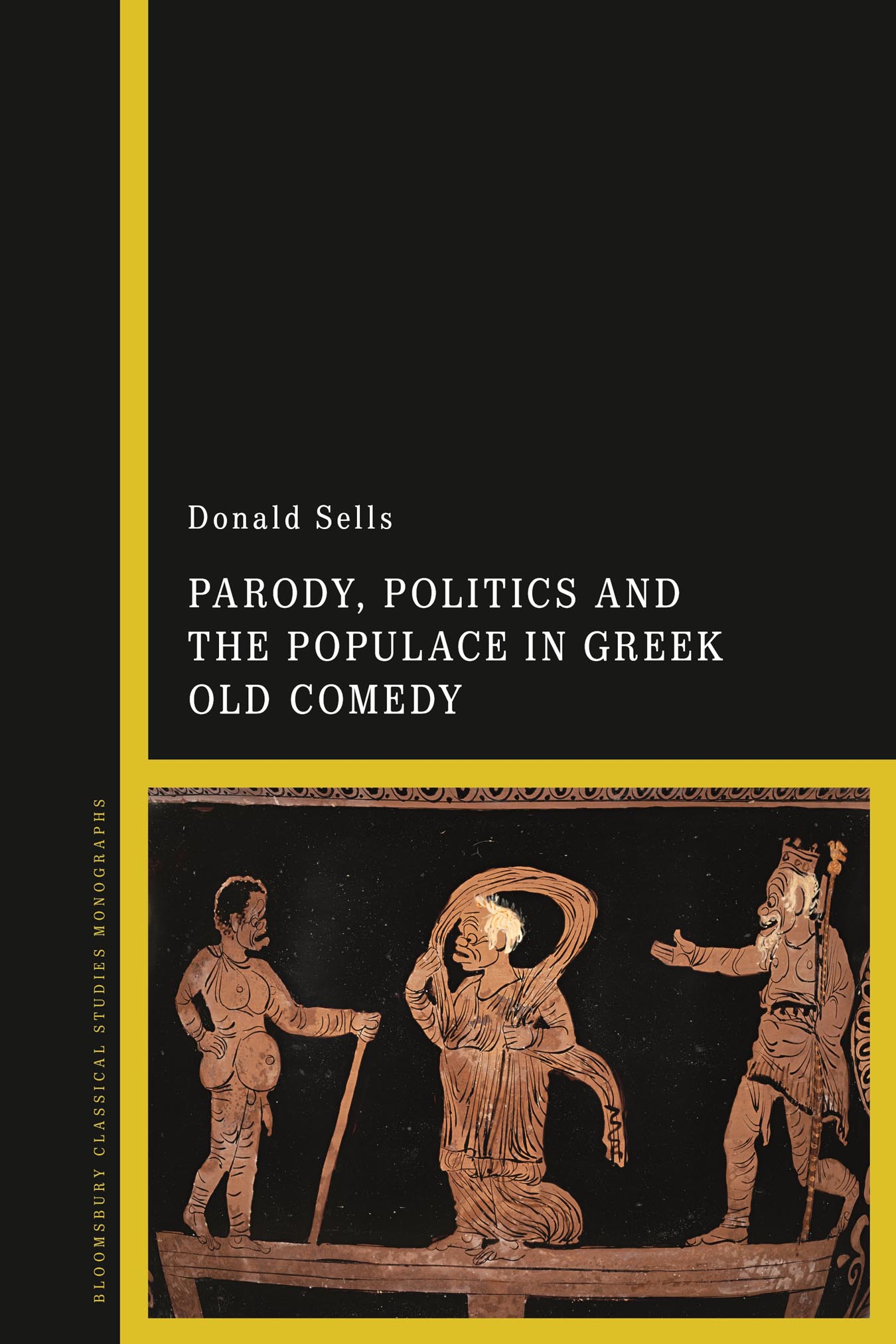

Parody, Politics and the Populace in Greek Old Comedy

Also available from Bloomsbury

Aristophanes, James Robson

Aristophanes and His Theatre of the Absurd, Paul Cartledge

Athenian Comedy in the Roman Empire, edited by C. W. Marshall and Tom Hawkins

The Comedian as Critic, Matthew Wright

No Laughing Matter, edited by C. W. Marshall and George Kovacs

Contents

Wrzburg Telephus, Inv. H5697 Martin von Wagner Museum der Universitt Wrzburg. Photo: P. Neckermann.

Berlin Heracles, formerly Berlin F3046, lost during the Second World War. Photo: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

Comic Phaedra. Red figure bell-krater from Lucania, Italy, 410390 BCE . Attributed to the Creusa Painter. NM2013.2 Nicholson Museum, The University of Sydney.

Rape of Ajax. Fragment of a Krater of Asteas. Villa Giulia, inv. 233879. Photo: Mauro Benedetti.

Priam and Neoptolemus, inv. 3045. Photo bpk Bildagentur I/Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Germany/Johannes Laurentius/Art Resource, NY.

Creon, Oedipus, and the Sphinx. Ragusa Collection 74. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto. Photo: Donald Sells.

The Sant Agata Antigone. Sant Agata Antigone dei Goti I. Rainone-Mustilli Collection. Reproduced with permission of the owner. Photos: Donald Sells.

The Getty Birds, inv. 205239. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

New York Goose Play. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

Boston Goose Play. Photograph 2018 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Mixing bowl (bell krater) with comic athletes in a palaestra. Greek, South Italian, Classical Period, c. 400390 BCE . Place of Manufacture: Italy, Apulia. Ceramic, Red Figure. Height: 28.6 cm (11 in.); diameter: 33 cm (13 in.) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Otis Norcross Fund 69.951.

Tragoidos (detail from New York Goose Play). Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

The Choregoi, inv. 248778. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

Cleveland Dionysus. Apulian Bell Krater, c. 390380 BCE . South Italy, Apulia, 4th century BC. Earthenware with slip decoration; overall: h. 38.00 cm (1415/16 inches); diameter of rim: w. 40.30 cm (1513/16 inches); diameter of foot: w. 18.40 cm (73/16 inches). The Cleveland Museum of Art, John L. Severance Fund 1989.73.

| Bernab | Bernab, A. (1987), Poetae Epici Graeci: Testimonia et Fragmenta Pars I, Leipzig: Teubner. |

| GMT | Goodwin, W.W. (1889), Syntax of the Moods and Tenses of the Greek Verb, London: Macmillan and Co. |

| KA | Kassel, R. and C. Austin (1983-2001), Poetae Comici Graeci, Vols 18, Berlin: De Gruyter. |

| KPS | Krumeich, R., N. Pechstein and B. Seidensticker, eds (1999), Das griechische Satyrspiel, Darmstadt: WBG. |

| LIMC | Lexicon Jconographicum Mythologiae Classicae, (19811999), 8 vols, Zurich and Munich: Artemis & Winkler. |

| Perry | Perry, B.E. (1952), Aesopica, Vol. 1, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. |

| PhV | Trendall, A.D. (1967), Phlyax Vases, 2nd edn, London: University of London. |

| PMG | Page, D.L. (1962), Poetae Melici Graeci, Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

| Radt | Radt, S. (1985), Tragicorum Graecorum Fragmenta, Vol. 3: Aeschylus, Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. |

| Radt, S. (1977), Tragicorum Graecorum Fragmenta, Vol. 4: Sophocles, Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. |

| RFVAp | Trendall, A.D. and A. Cambitoglou (1978), The Red-Figure Vases of Apulia, Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

| RFVAp suppl. | Trendall, A.D. and A. Cambitoglou (1991), Second Supplement to the Red-Figure Vases of Apulia, i, London: University of London. |

The beginning of my comic project was the summer of 2003 when Ralph Rosen recommended the comic fragments as an excellent starting point for research on Old Comedy.

I am extremely grateful to those who have read and commented on individual chapters: Stelios Chronopoulos, Chris Eckerman, Lizzie Nabney, Lisa Nevett, Amy Pistone, Chris Ratt, David Roselli, Piero Totaro, Victoria Wohl. I also thank those who read the whole manuscript at an early stage: Carl Anderson, Sara Forsdyke, Tom Hubbard, Ralph Rosen, and Celia Schultz. Richard Janko, Celia Schultz, Ruth Scodel and Alan Sommerstein gave me feedback on various parts of the book throughout the process.

With funds provided by the Bruce Frier Fund of the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan I was able to examine firsthand many of the vases featured in this study. For help acquiring images and permissions, I would like to thank Alessia Argento (Villa Giulia), the Mustilli Family and Arianna Sacerdoti (Naples).

I thank Bloomsburys two anonymous readers for many perceptive comments and much encouragement. I am especially grateful to Alice Wright and Emma Payne for patiently shepherding me through the publication process. Christian Axelgard and Nick Geller provided excellent proofreading and comments. Molly Schaub and Scott Morton helped with the indices and bibliography.

Finally, I thank my mentors at Michigan. Scholars in Classics are extremely lucky to be mentored by one eminent scholar. I had two, Richard Janko and Ruth Scodel. I will always be grateful for their support during the process of writing this book.

My greatest debt is to my mom, the strongest person I know.

I. Studying parody in Old Comedy

Unfortunately, we know very little about the real-world impact of parody in fifth-century Greek comedy on Athenian society. Nevertheless, scholars continue to study important aspects of this timeless phenomenon of popular culture on its own terms. Since Peter prestige genres of fifth-century performance culture tragedy, satyr play and lyric as a means of raising the public profile of the individual poet and the genre as a whole.

In the most significant contribution to the subject since

Apart from texts, the iconography of Attic and South Italian vase painting and plastic art preserves a store of extant evidence for late fifth-century and early fourth-century parody. Important studies of such theatre-related material remind us of something easily forgotten in our text-centred discipline: that parody in performance is a visual experience and had a distinctive impact on audiences. Recognizably parodic iconography of this kind preserves valuable testimony for the performative mechanisms of such parody, balancing and occasionally supplementing our textual evidence. Its thematic and narrative evidence reveals the concepts driving such mechanisms, counterfactual experiments, and unparalleled cross-generic scenarios. This studys integration of theatre-related vase paintings with literary evidence thus presents a fuller and more comprehensive picture of fifth-century comic appropriation.

II. Expectations, seriousness and society

The varieties of Aristophanic paratragedy show that the appropriation of other poetic forms cannot easily be reduced to one common, single mechanism or effect. I have already used several terms parody, paratragedy, appropriation etc. to describe the topic. Throughout this investigation, I adhere to, and occasionally paralyric that seemingly lack parodys subversive intent.

Next page