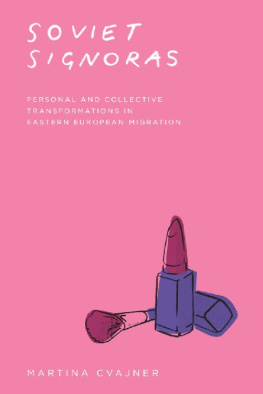

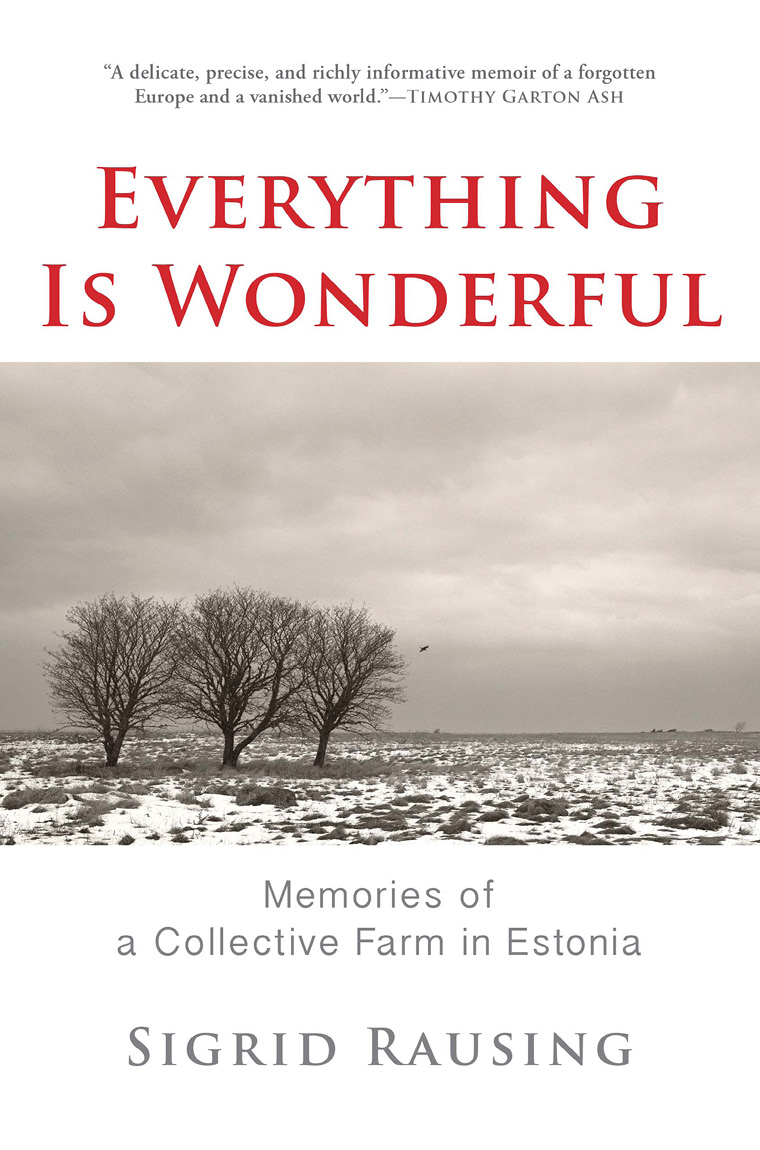

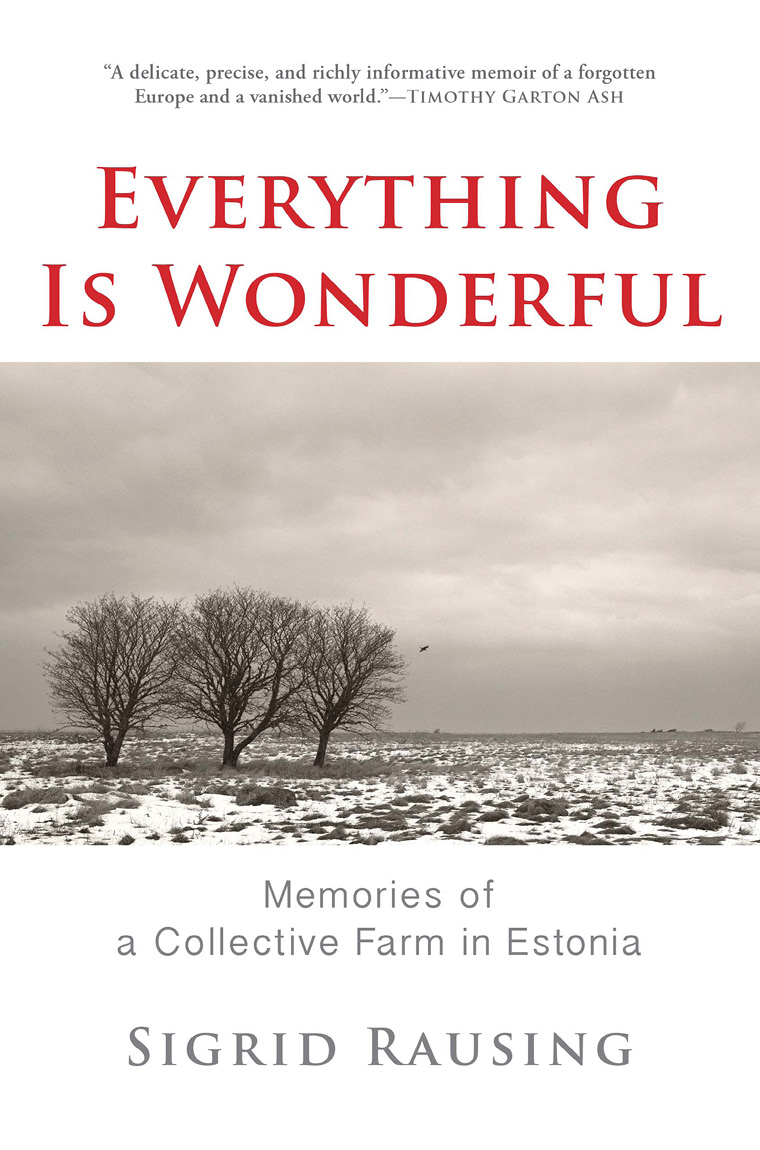

E VERYTHING I S W ONDERFUL

SIGRID

RAUSING

E VERYTHING I S W ONDERFUL

Memories of a Collective Farm

in Estonia

Grove Press

New York

Copyright 2014 by Sigrid Rausing

Jacket photograph Pentii Sammallahti

Author photograph Paul Stuart

If I Wanted to Go Back by Jaan Kaplinski, translated from Estonian by Jaan Kaplinski and Sam Hamill. Copyright Jaan Kaplinski and Sam Hamill and reproducedwith their kind permission

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011, or .

Maps copyright 2014 by Martin Lubikowski

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-0-8021-2217-9

eBook ISBN: 978-0-8021-9-2813

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

To Hans and Mrit

Contents

North-Eastern Europe, 1989

The Republic of Estonia

Everything Is Wonderful

Preface

I have a photograph in front of me from the winter of 1993: a dilapidated barn stands on a snow-covered field, the blue and faint orange of the afternoon sky reflected in the snow. The field is in Estonia, on a former collective farm in a remote area on the west coast. The barn looks isolated and slightly melancholy on the vast field, having survived war, land reform, collectivisation, and, now, privatisation. The photograph is one of many. I also have a diary, and many letters and notebooks.

I lived on the collective farm for a year in 199394, gather ing material for a PhD in social anthropology about history and memory. I was there to study the local perception and understanding of historical events in the context of the Soviet repression and censorship of history. I wanted to understand how the people on this peninsula understood their history, and how the war and occupations had affected them and their families. My PhD became an academic book, History, Memory, and Identity in Post-Soviet Estonia : The End of a Collective Farm , published by Oxford University Press in 2004. Parts of that book are replicated here. It was based on those same notes and the diary, though purged, of course, of anything personal. I make reference to Orwell in that book and in this, and the same characters appear through the pages. I hesitate to say that this book is more authenticthe real account of what actually happenedsince scholarship was as much or more a part of my experience of being there as the daily life in this story. Much as my academic book excluded the personal, this book excludes the academic, but anyone who reads both will see that they overlap to some degree.

Estonia went through a war, and occupationsfirst by the Soviet Union and then by Nazi Germanyso devastating, and so violent, that nearly a quarter of the population had fled, disappeared, or been killed by the end of it. The population declined from 1,136,000 people to 854,000. Nor did the violence end with peace: the terror and repression continued in the second Soviet occupation. The mass deportation from the countryside in March 1949 was timed to weaken resistance to the planned forced collectivisation. My collective farm, encompassing some twenty villages and most of the land on the peninsula of Noarootsi, was formed shortly after the deportations. It was officially closed down in February 1993, following a vote by all the members in which just one person voted for its continued existence.

I had moved to England from Sweden in 1980. Part of my interest in this particular area was that before the war, some half of the people on the peninsula had been Swedish-speaking, belonging to the Swedish minority of Estonia. The Estonian Swedes lived on the west coast and on the islands they had lived there since the Middle Ages, fishing, trading, and farming. In 1944, in the dying days of the Nazi occupation of Estonia, the majority of the Swedes, some seven thousand people out of a total population of eight thousand, were evacuated by the Nazis. The Swedish government paid a fee per person to the Nazis, and saved the Swedes from the coming Soviet occupation, but the deal was, of course, tainting, and the refugees were encouraged not to talk about it, and to assimilate in Sweden as best they could.

In the early 1990s, on Noarootsi, you could still sense the effects of the evacuation, and the ravages of war and deportations. It was a bleak and depopulated area. Prksi, where I lived, was the only village on the peninsula that had slightly increased its population since the census of 1934. All the other villages had declined dramatically, the largest shrinking from 480 people to 59, the smallest from 69 to 16. The total population was no more than a few hundred people.

The peninsula had been a Soviet military border protection zone, with limited public access. It had a permanent army base, and there was only one road out to the mainland, patrolled by soldiers on duty by a barrier. The barrier was still there when I arrived, but the soldiers were gone. Before independence, people crossing to the peninsula had to show their papers at the barrier, no matter how well known they were, or how often they crossed over. The coast was heavily guarded. At regular intervals along the whole coastline there were watchtowers with powerful searchlights. In some places people were not allowed access to the sea.

When I first visited Prksi, in April 1993, there were some signs of progress. There was a new shop, and the church, the vicarage, and the manor house were being restored with funds from abroad. There were, also, many signs of post-Soviet decline. The communal dining room had been closed down, as had the crche; the weekly cultural programme had been cancelled, the cold and dusty culture hall was empty, and there was little heating or hot water. The ruling Isamaa (Fatherland) coalition was, people said, building capitalism. People endured the sacrifices, with not much hope for the future, much as they had when the state was building socialism. Poverty, and drinking, shortened lives, especially for men. Life expectancy in 1994 dipped to sixty years for men and just under seventy-three years for women. By 2012 it had increased to about sixty-eight and seventy-nine years, respectively.

The centre of Prksi was a dusty square formed by the school, where I was to work as an English teacher, the culture hall, and the old workshops at the far end. At the back of the culture hall was Gorbyland, the basement bar named after Mikhail Gorbachev, whose attempts to curb the pervasive Soviet alcoholism were considered mildly amusing. There, also, was the rubbish dump; a pile of plastic bags torn apart by the village dogs, lit by a single bleak floodlight at night. There was a new little cooperative shop near the workshops. By the road coming into the village was the dairy, defunct since the 1970s, and the old Soviet shop, selling household stuff as well as some food, pots and pans, exercise books, shoes if they got a consignment, and ancient Russian jars of jams and pickles with rusty lids and falling-off labels. On the wide, low windowsill the alcoholics sat and drank in peaceful camaraderie. The atmosphere was quiet, almost somnolent.

Next page