Reading Iraqi Womens Novels in English Translation

By exploring how translation has shaped the literary contexts of six Iraqi woman writers, this book offers new insights into their translation pathways as part of their stories politics of meaning-making.

The writers in focus are Samira Al-Mana, Daizy Al-Amir, Inaam Kachachi, Betool Khedairi, Alia Mamdouh and Hadiya Hussein, whose novels include themes of exile, war, occupation, class, rurality and storytelling as cultural survival. Using perspectives of feminist translation to examine how Iraqi womens story-making has been mediated in English translation across differing times and locations, this book is the first to explore how Iraqi womens literature calls for new theoretical engagements and why this literature often interrogates and diversifies many literary theories geopolitical scope.

This book will be of great interest for researchers in Arabic literature, womens literature, translation studies and women and gender studies.

Ruth Abou Rached is an Honorary Research Associate at the University of Southampton and specialises in teaching Translation Studies, Modern Foreign Languages and Arabic studies to widen university access to under-represented groups. Her work on Iraqi womens literature was inspired by her community work in the UK and living in the Middle East. Her research interests include Iraqi and Arab womens writing, Palestinian and other exilic literatures, postcolonial studies and intersectional feminist translation theories. She is editor for New Voices in Translation Studies, International Association of Translation and Intercultural Studies (IATIS).

Focus on Global Gender and Sexuality

Trans Dilemmas

Stephen Kerry

Gender, Sport and the Role of the Alter Ego in Roller Derby

Colleen E. Arendt

The Poetry of Arab Women from the Pre-Islamic Age to Andalusia

Wessam Elmeligi

Interviews with Mexican Women

We Dont Talk About Feminism Here

Carlos M. Coria-Sanchez

Pornography, Indigeneity and Neocolonialism

Tim Gregory

Reading Iraqi Womens Novels in English Translation

Iraqi Womens Stories

Ruth Abou Rached

For a full list of titles in this series, please visit www.routledge.com/Focus-on-Global-Gender-and-Sexuality/book-series/FGGS

First published 2021

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2021 Ruth Abou Rached

The right of Ruth Abou Rached to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN: 978-0-367-85717-2 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-003-01456-0 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

Contents

: Samira Al-Mana and Daizy Al-Amir

: Inaam Kachachi

: Betool Khedairi

: Alia Mamdouh and Hadiya Hussein

Guide

For the transcription of Arabic language citations, this study follows the style used by ALA-LC (American Library Association Library of Congress).

Titles of Arabic publications are listed in Arabic, with no ALA-LC transliterations. Titles are back-translated into English between square brackets for ease of reference.

For Arab authors with publications in a language other than Arabic, their names are kept in the form used with their publications. Arabic words or titles taken from authors quotations are kept in the form transcribed by them.

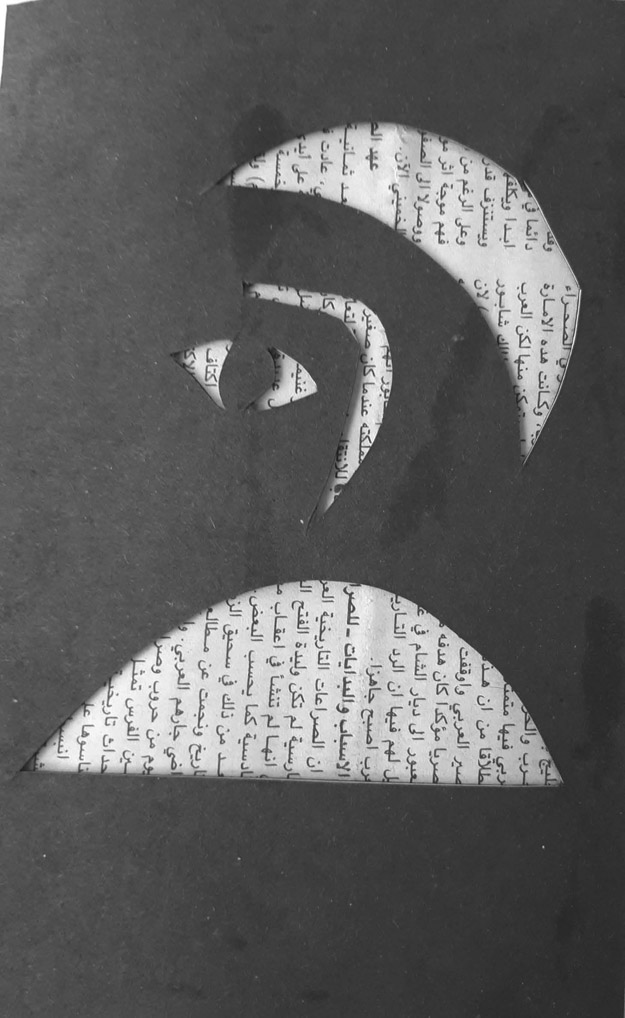

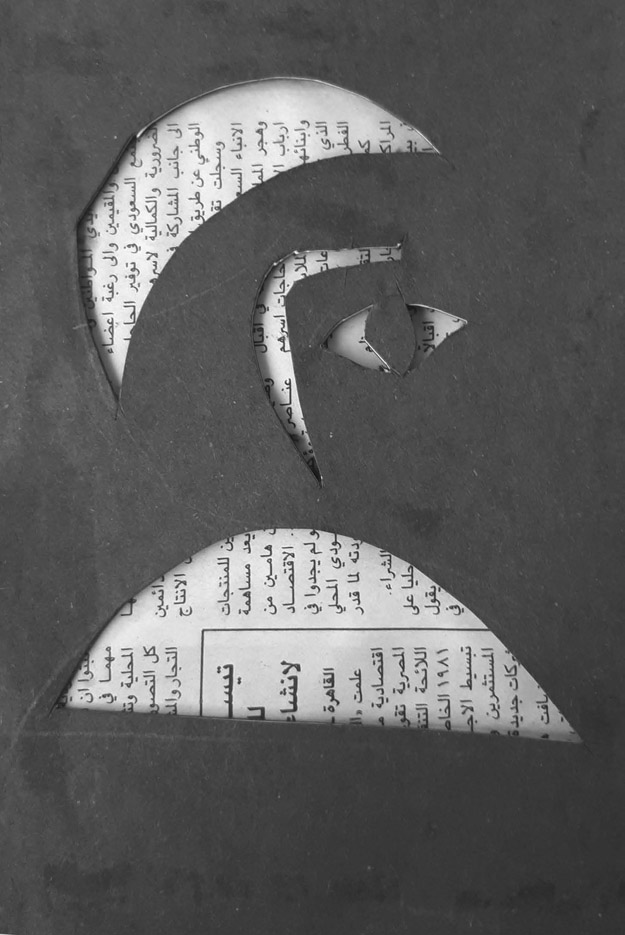

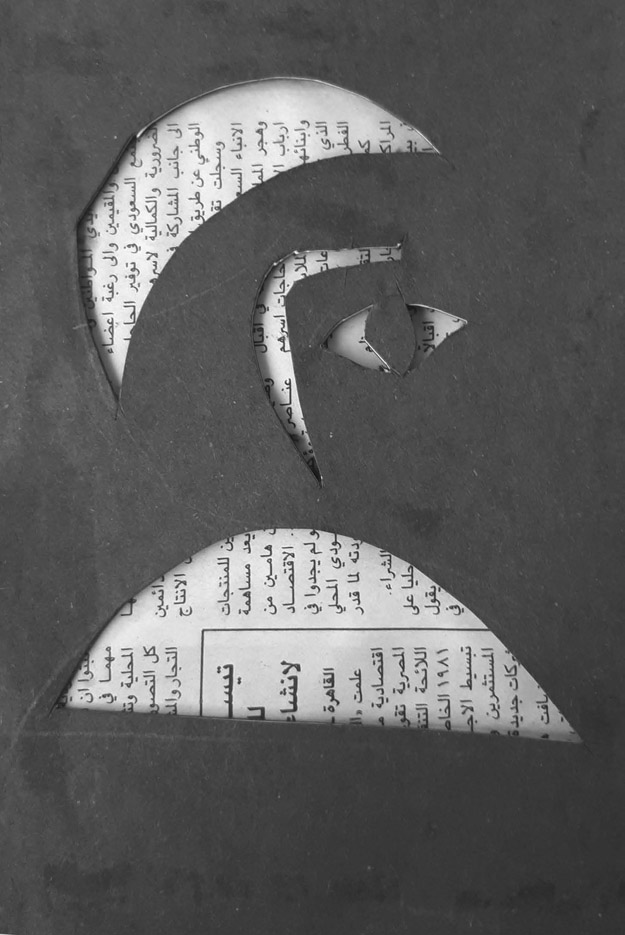

Mediterranean Summer (1989), Sarah Niazi

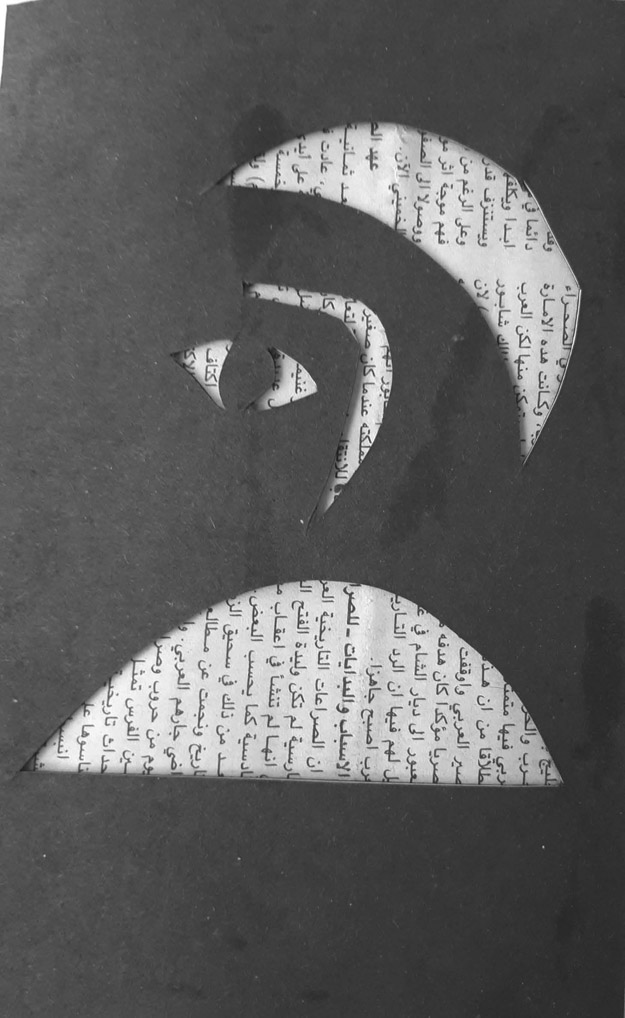

Girl Under the Moon (1988), Sarah Niazi

Girl Under the Moon (1988), Sarah Niazi

1

Pathways of Iraqi womens story-writing in English translation

At a literary event on Iraqi literature held in Berlin in 2020, Syrian-Palestinian poet Ghayath Almadhoun remarked that everyone in the Middle East, particularly Iraq, seems to be waiting in line to tell their stories of war, dictatorship, survival and exile. Iraqi women writers have not been spending time waiting: for decades they have been writing their other Iraqis stories of hope and survival, many engaging with translation as part of their creative expression and literary activism. Little, however, has been written on how stories written by Iraqi women writers have been mediated or re-written in English translation. This gap is surprising in view of Iraqs high international profile for decades. As a response to this gap, this book explores how six examples of Iraqi womens story-making have been mediated in English translation across different times, political contexts and locations. The writers in focus are Samira Al-Mana, Daizy Al-Amir, Inaam Kachachi, Betool Khedairi, Alia Mamdouh and Hadiya Hussein, six Iraqi women writers who have turned to translation as one way of preserving their stories and stories of many other Iraqis beyond conventional borders.

Samira Al-Mana and Daizy Al-Amir were amongst the first Iraqi women writers to publish stories in Beirut during the 1960s. Inaam Kachachi writes stories to archive alternative histories of Iraq as amulets of memory (Snaije 2014). Betool Khedairi works to archive photos of Iraq through her creative writing. For decades Alia Mamdouh has challenged the many languages of patriarchy via her innovative use of Arabic. Hadiya Hussein writes to show Iraqs beauty while addressing fear, specifically the fears of an Iraqi citizen who has become even more fearful of a slip of the tongue than an actual, physical slip (Hussein cf. Lynx-Qualey 2013). Drawing on analytical frameworks of intersectional feminist translation, I show how one story of each writer has moved across its many charged borders, some of which included changes of government, deteriorating infrastructure and ongoing conflict in Iraq. English translation is, of course, not the only way by which Iraqi women writers communicate their stories with different readerships, and story-writing is not the only way that Iraqi women express their literary activism. Innovative literature by Iraqi women, particularly during the early years of their story-writing yet to be translated or to circulate outside Iraq (Abou Rached 2020, 5151) also merits much more critical attention. Poetry, theatre, art and music are also just four of the many rich categories of Iraqi expression which are beyond the scope of this book.