FIRST VINTAGE INTERNATIONAL EDITION, JANUARY 2007

Copyright 1972 by James Baldwin,

copyright renewed 2000 by Gloria Baldwin Karefa-Smart

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by The Dial Press, New York, in 1972.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage International and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress.

eISBN: 978-0-8041-4966-2

www.vintagebooks.com

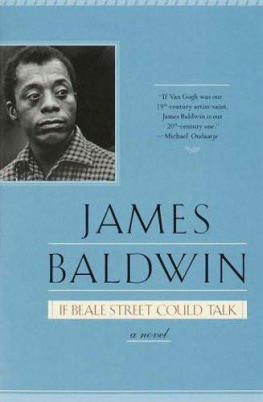

Cover design by Helen Yentus

Cover images: (top) Bruce Davidson / Magnum Photos

(bottom) /Amer Ghazzal / Millennium Images, UK (detail)

v3.1

for

Berdis Baldwin

and

Beauford DeLaney

and

Rudy Lombard

and

Jerome

Contents

His remembrance

shall perish from the earth

and He shall have

no name in the street.

He shall be driven from light

into darkness,

and chased out of the world.

Job 18:17-18

If I had-a- my way

Id tear this building down.

Great God, then, if I had-a- my way

If I had-a- my way, little children,

Id tear this building down.

Slave Song

Just a little while to stay here,

Just a little while to stay.

Traditional

take me to the water

That is a good idea, I heard my mother say. She was staring at a wad of black velvet, which she held in her hand, and she carefully placed this bit of cloth in a closet. We can guess how old I must have been from the fact that for years afterward I thought that an idea was a piece of black velvet.

Much, much, much has been blotted out, coming back only lately in bewildering and untrustworthy flashes. I must have been about five, I should think, when I made my connection between ideas and velvet, but I may have been younger; this may have been the same year that my father had me circumcised, a terrifying event which I scarcely remember at all; or I may think I was five because I remember tugging at my mothers skirts once and watching her face while she was telling someone else that she was twenty-seven. This meant, for me, that she was virtually in the grave already, and I tugged a little harder at her skirts. I already knew, for some reason, or had given myself some reason to believe, that she had been twenty-two when I was born. And, though I cant count today, I could count when I was little.

I was the only child in the houseor housesfor a while, a halcyon period which memory has quite repudiated; and if I remember myself as tugging at my mothers skirts and staring up into her face, it was because I was so terrified of the man we called my father; who did not arrive on my scene, really, until I was more than two years old. I have written both too much and too little about this man, whom I did not understand till he was past understanding. In my first memory of him, he is standing in the kitchen, drying the dishes. My mother had dressed me to go out, she is taking me someplace, and it must be winter, because I am wearing, in my memory, one of those cloth hats with a kind of visor, which button under the china Lindbergh hat, I think. I am apparently in my mothers arms, for I am staring at my father over my mothers shoulder, we are near the door; and my father smiles. This may be a memory, I think it is, but it may be a fantasy. One of the very last times I saw my father on his feet, I was staring at him over my mothers shouldershe had come rushing into the room to separate usand my father was not smiling and neither was I.

His mother, Barbara, lived in our house, and she had been born in slavery. She was so old that she never moved from her bed. I remember her as pale and gaunt and she must have worn a kerchief because I dont remember her hair. I remember that she loved me; she used to scold her son about the way he treated me; and he was a little afraid of her. When she died, she called me into the room to give me a presentone of those old, round, metal boxes, usually with a floral design, used for candy. She thought it was full of candy and I thought it was full of candy, but it wasnt. After she died, I opened it and it was full of needles and thread.

This broke my heart, of course, but her going broke it more because I had loved her and depended on her. I knewchildren must knowthat she would always protect me with all her strength. So would my mother, too, I knew that, but my mothers strength was only to be called on in a desperate emergency. It did not take me long, nor did the children, as they came tumbling into this world, take long to discover that our mother paid an immense price for standing between us and our father. He had ways of making her suffer quite beyond our ken, and so we soon learned to depend on each other and became a kind of wordless conspiracy to protect her. (We were all, absolutely and mercilessly, united against our father.) We soon realized, anyway, that she scarcely belonged to us: she was always in the hospital, having another baby. Between his merciless children, who were terrified of him, the pregnancies, the births, the rats, the murders on Lenox Avenue, the whores who lived downstairs, his job on Long Islandto which he went every morning, wearing a Derby or a Homburg, in a black suit, white shirt, dark tie, looking like the preacher he was, and with his black lunch-box in his handand his unreciprocated love for the Great God Almighty, it is no wonder our father went mad. We, on the other hand, luckily, on the whole, for our father, and luckily indeed for our mother, simply took over each new child and made it ours. I want to avoid generalities as far as possible; it will, I hope, become clear presently that what I am now attempting dictates this avoidance; and so I will not say that children love miracles, but I will say that I think we did. A newborn baby is an extraordinary event; and I have never seen two babies who looked or even sounded remotely alike. Here it is, this breathing miracle who could not live an instant without you, with a skull more fragile than an egg, a miracle of eyes, legs, toenails, and (especially) lungs. It gropes in the light like a blind thingit is, for the moment, blindwhat can it make of what it sees? Its got a little hair, which its going to lose, its got no teeth, it pees all over you, it belches, and when its frightened or hungry, quite without knowing what a miracle its accomplishing, it exercises its lungs. You watch it discover it has a hand; then it discovers it has toes. Presently, it discovers it has you, and since it has already decided it wants to live, it gives you a toothless smile when you come near it, gurgles or giggles when you pick it up, holds you tight by the thumb or the eyeball or the hair, and, having already opted against solitude, howls when you put it down. You begin the extraordinary journey of beginning to know and to control this creature. You know the soundthe meaningof one cry from another; without knowing that you know it. You know when its hungrythats one sound. You know when its wetthats another sound. You know when its angry. You know when its bored. You know when its frightened. You know when its suffering. You come or you go or you sit still according to the sound the baby makes. And you watch over it where I was born, even in your sleep, because rats love the odor of newborn babies and are much, much bigger.