WARNING: A responsible adult should supervise any young reader who conducts the experiments in this book to avoid potential dangers and injuries. The author has conducted every experiment in this book and has made every reasonable effort to ensure that the experiments are safe when conducted as instructed. However, the author and publisher of this book disclaim all liability incurred in connection with the use of the information contained in this book.

Copyright 2018 by Joey Green

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in review.

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61373-959-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Green, Joey, author.

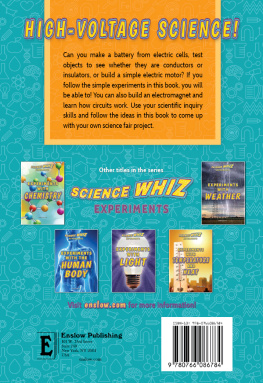

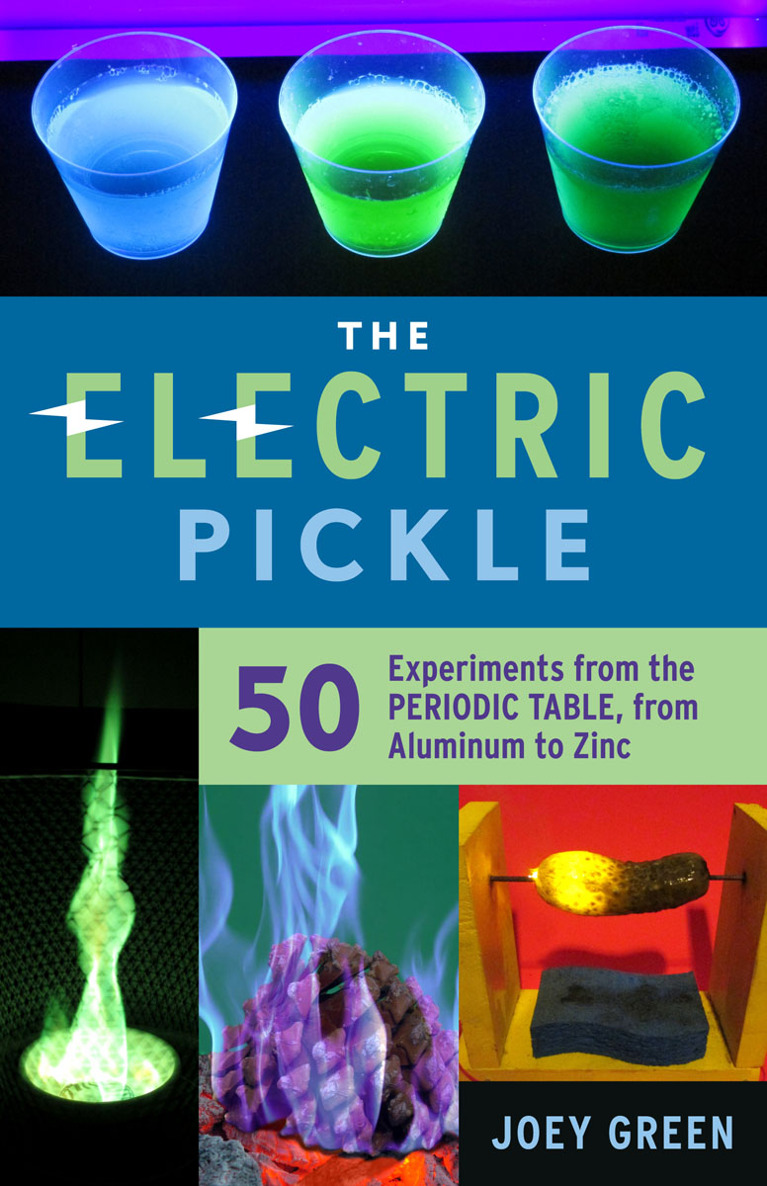

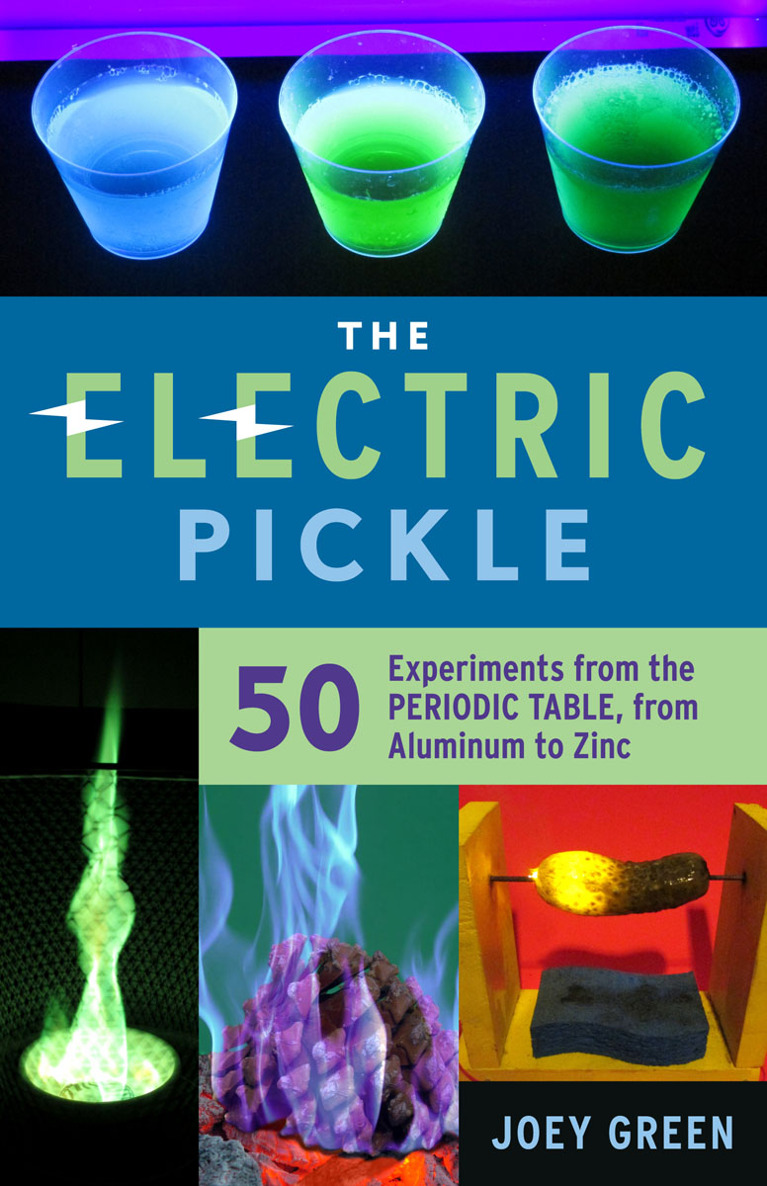

Title: The electric pickle : 50 experiments from the periodic table, from aluminum to zinc / Joey Green.

Description: Chicago, Illinois : Chicago Review Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017001557 (print) | LCCN 2017001881 (ebook) | ISBN 9781613739600 (pdf) | ISBN 9781613739624 (epub) | ISBN 9781613739617 (Kindle) | ISBN 9781613739594 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: ChemistryExperiments. | Chemical elements. | ElectricityExperiments. | Periodic table of the elements.

Classification: LCC Q164 (ebook) | LCC QD38 .G74 2018 (print) | DDC 540.78dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017001557

Cover design: Andrew Brozyna

Cover and interior images: Debbie Green

Interior design: Jonathan Hahn

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

If it squirms, its biology.

If it stinks, its chemistry.

If it doesnt work, its physics.

And if you cant understand it, its mathematics.

M AGNUS P YKE, B RITISH SCIENTIST

CONTENTS

Introduction

I n the mid-19th century, airship inventors and builders filled the first airshipsmore commonly known as dirigibles, zeppelins, and blimpswith hydrogen, the lightest gas known, causing the airships to rise high into the sky. Weighing only about 7 percent of an equal volume of air, hydrogen can be produced by the electrolysis of water, in which an electric current breaks down the water into its two elements: hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen, however, is extremely flammable. In 1937, while approaching Lakehurst, New Jersey, on a flight from Germany, the Hindenburg, the largest airship in its day, exploded and burst into flames in the first air disaster recorded on film. The crash destroyed the Hindenburg in 34 seconds, ended the use of airships for regular passenger service, and raised an obvious question: Why not use nonexplosive helium instead?

In 1896, French physicist Henri Becquerel discovered that minerals containing uranium emitted X-rays. Physicist Marie Curie, having received her masters degree from the Sorbonne, decided to investigate the uranium rays, setting up a laboratory in a storeroom in the Paris Municipal School, where her husband, Pierre Curie, was a professor. After discovering that compounds containing the uncommon element thorium also emanated rays, Marie invented the term radioactivity to describe the atomic property of the two chemical elements. Together with her husband, Marie discovered two more radioactive elements: polonium and radium. In 1903 she became the first woman to receive a doctorate in France and the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize. Refusing to believe that radiation was harmful, Marie died of leukemia on July 4, 1934, plausibly due to exposure to high levels of radiation emitted by the radioactive elements she had been studying during the previous four decades.

Now Im not advocating that you play with radioactive elements or set fire to a balloon filled with hydrogen, but I can tell you that the most dangerous science experimentslaunching rockets, mixing up weird chemicals, splitting atoms, or playing with a particle acceleratordo tend to be the most exciting. Until youve walked on eggs, powered a rocket with Diet Coke and Mentos, or turned an ordinary pickle into a lightbulb that throws off hot orange sparks, you really havent lived life to the fullest. Theres something strangely exhilarating about shrinking a potato chip bag to the size of a domino, microwaving a lightbulb, or creating an explosive fireball with cornstarch.

Is there any way to justify this downright kooky behavior? Oddly, yes. Scores of amazingly intelligent people who have pursued careers in science share a love for blowing up things and putting themselves in harms way. In the 1920s, when rocket scientist Robert H. Goddard saw his first four attempts at launching a rocket blow up on the launch pad, Im guessing his first thought was something along the lines of Cool! In 1899, Serbian American inventor Nikola Tesla sent a heavy electrical current through the coils wrapped around a tower 80 feet in height and up a 142-foot-tall metal pole topped by a 3-foot-diameter copper ballproducing bolts of artificial lightning that measured up to 135 feet long, generating thunder heard fifteen miles away, and inadvertently knocking out the electrical power station in Colorado Springs. In 1924, at the age of 12, future aerospace engineer Wernher von Braun strapped six fireworks rockets to his toy wagon, ignited them, and shot off across a crowded Berlin streetwhere a police officer apprehended him.

The eccentric experiments in this book spark the imagination, bring science to life, create excitement about how the world works, demonstrate the undeniable beauty and importance of science, and enhance your understanding of the most common elements in the periodic tablethe unique substances that cannot be broken down or made into anything simpler by chemical reactions. Scientists have identified more than 110 elements, and the experiments in this book involve only those elements (or a compound that includes the specific element) that are easily available and safe to handle. In some cases the experiments focus on the basic attributes of a particular element rather than directly on the element itself. Unfortunately, conducting these experiments also comes with the danger that society might label you a geek, weirdo, or nutjob. The good news? Youll be in excellent company. Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Alva Edison, Robert Goddard, Albert Einsteinat one time they were all considered ditzy crackpots.

Of course, everything in life is potentially dangerous. Simply flipping through the pages of this book can give you a painful paper cut, and boiling a pot of water can cause third-degree burns, should you accidentally bump the pot, spilling boiling water all over yourself. Remember, accidents happen, and any science experiment, regardless of its simplicity or how precisely you follow the instructions, can be unpredictable. Even if youre working with harmless ingredients, take the proper precautions by wearing appropriate safety equipment, following the delineated procedures, securing adult supervision when necessary, and concentrating on what you are doing. While I have personally conducted all the experiments in this book and thoroughly reviewed the described instructions, please be cautious when performing the experiments. Im sure Marie Curie would have loved conducting every project with reckless abandon. But I urge you to wear gloves to protect yourself from possible paper cuts.

Next page