Copyright 2012 Alex Russell and Tim Falconer

All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced or used in any form or by any meansgraphic, electronic or mechanical without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any request for photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems of any part of this book shall be directed in writing to The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright license, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free 18008935777.

Care has been taken to trace ownership of copyright material contained in this book. The publisher will gladly receive any information that will enable them to rectify any reference or credit line in subsequent editions.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Russell, Alex, 1965

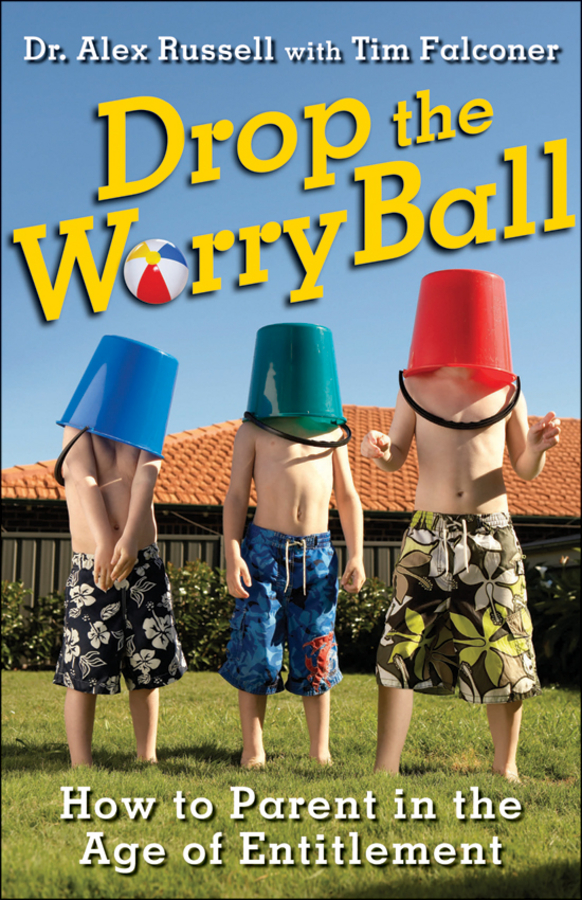

Drop the worry ball : how to parent in the age of entitlement / Alex Russell, Tim Falconer.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-11812-494-9

1. Parent and child. 2. Parental acceptance. 3. Failure

(Psychology) in children. I. Falconer, Tim, 1958- II. Title.

HQ755.8.R88 2012 649'.1 C2011-907376-5

ISBN 978-1-118-12494-9 (pbk); 978-1-118-16217-0 (ebk); 978-1-118-16257-6 (ebk); 978-1-118-16331-3 (ebk)

Production Credits

Interior design: Pat Loi

Cover design: Adrian So

Cover photo: Steve Baccon/Thinkstock

Production Editor: Lindsay Humphreys

Composition: Laserwords

Printer: Friesens Printing Ltd.

John Wiley & Sons Canada, Ltd.

6045 Freemont Blvd.

Mississauga, Ontario

L5R 4J3

Full of what is passing in your own head, you do not see the effect you are producing in theirs.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, mile, or On Education (1762)

Introduction

A mother struggling with her tween daughter consulted the family doctor. He offered a number of suggestions and wrote down some titles of parenting books she could read. As mother and daughter left his office, he tried to be reassuring: Everything will be fine. Try to stay calm and just take baby steps.

A few days later, the daughter started acting up again, which upset the mother. Mom! Do what the doctor said, the girl instructed, as Mom slowly lost it once again. Take baby steps!

So what do I do now? she asked when she came to me.

Good question. But I knew better than to simply give her more advice because, at a certain point, advice does more harm than good. Parenting guides began appearing in the 19th century and helped spur the professionalization of parenting. That led to the great shift away from the long history of tyranny over and abuse of children, although in hindsight we know that not all the rules experts dreamed up were good ones. For half a century many doctors even discouraged mothers from breastfeeding their babies. But, more than that, all the advice has led to the steady erosion of parental confidence and our ability to rely on our own intuition.

After 200 years of guides that have often meant as much grief as help, my goal is to provide a different perspective on your relationship with your children and help you reconsider your ideas about the role of a parent. Simply offering more pointers may just deepen your sense of obligation and your need to get it just right. So this book is not a blueprint for parenting and I've kept the tips, guidelines and commandments to a minimum and concentrated on helping you rethink how you do the most important job any of us will ever take on.

I first started thinking about writing this book five years ago. The idea sprang from my work with children and their parents and with schools. As a clinical psychologist, I deal with a wide range of problems, but over the past decade I've increasingly found myself helping families in the same predicament: children struggling to take on the challenges of school and the big world outside the family home, while increasingly anxious parents and educators work harder and harder to get them on track.

Sometimes these are kids who are underachieving, putting in a minimum of effort and seemingly unable to appreciate the basics of what people need to do in the world (pay attention to various responsibilities, care about the way we treat others, think ahead). These children and teenagers have a worrying sense of entitlement, as if they have the right to spend their lives in pleasurable pursuitsplaying or chilling all day, every dayor at least free from any kind of hardship.

Sometimes experts diagnose children with Attention Deficit Disorder or a learning disability. Identifying these issues can be extremely helpful, but for some families, while the diagnosis sheds light on a child's areas of weakness, it doesn't do anything to solve the pressing problems in the family: Johnny's lack of engagement with school and his parents' increasing frustration with him.

Sometimes the diagnosis refers to emotional problems such as depression or anxiety. Anxiety is on the rise among our children, and when I am not seeing a child who is disengaged from school and achievement, chronically avoiding the stress (anxiety) of school and the big world out there, I am often seeing the opposite: a kid who has entirely bought into the whole competitive, marks-oriented school system we have created, and suffers from anxiety symptoms such as panic attacks, sleep and eating problems, and painfully obsessive behavior. While these children often achieve well, their orientation to school and broader reality is troubling: they're able to enjoy their achievement to some extent, but their engagement with the world is not particularly rewarding or even interesting to them. It's about the marks, not the subject matter. By the time they suffer from open anxiety and even panic attacks, their parents' central concern is no longer about school and achievement. It's about their child's unhappiness, and their main goal is now to get her interacting in a more playful and rewarding way with the world around her.

I've found that when parents gain a new perspective on raising children, from infancy on up, they're able to develop relationships with their children that are close and supportive. Under these conditions, children grow up to be young adults who are ready to leave home and thrive in the big world out there. To be successful, parents must avoid getting sucked into today's over-parenting culture, and instead provide children with what they actually need: loving support and attention that gives them the confidence and sense of personal responsibility required to take on the world for themselves.

I warn you, though: it's not always easy to play this patient, attentive and non-bossy role. You will have to learn to accept that kids are completely capable of worrying for themselves, that failure is an essential learning experience, and that sometimes it's better to stand back and say little or nothing because watching is often more powerful than acting. Toughest of all may be facing the prospect that once you adopt this new approach, some problems may actually get worse before they get better. But they will get betterthey always do if parents successfully become compassionate, interested bystanders who are ready to step in when necessary while safeguarding against the real dangers and catastrophic failures that do children no good at all.

Figuring out how to help those caught up in the Age of Entitlement would not have been possible without the families who have shared their difficulties with me over the past decade. Their stories appear throughout the book, although I have freely altered details, switching genders and races, and often combining elements from different cases into one, in order to get a point across. In fact, the stories in this book come from many places, including my own experiences as both a kid and a parent and those of my friends, as well as from the children and parents I have worked with as a psychologist trying to understand these problems.