Note

Safari Books Online (www.safaribooksonline.com) is an on-demand digital library that delivers expert content in both book and video form from the worlds leading authors in technology and business.

Technology professionals, software developers, web designers, and business and creative professionals use Safari Books Online as their primary resource for research, problem solving, learning, and certification training.

Safari Books Online offers a range of product mixes and pricing programs for organizations, government agencies, and individuals. Subscribers have access to thousands of books, training videos, and prepublication manuscripts in one fully searchable database from publishers like OReilly Media, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, Course Technology, and dozens more. For more information about Safari Books Online, please visit us online.

How to Contact Us

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

| OReilly Media, Inc. |

| 1005 Gravenstein Highway North |

| Sebastopol, CA 95472 |

| 800-998-9938 (in the United States or Canada) |

| 707-829-0515 (international or local) |

| 707-829-0104 (fax) |

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at http://oreil.ly/css-fonts_1e.

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to .

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

Chapter 1. Fonts

As the authors of CSS clearly recognized from the outset, font selection is a popular, indeed crucial, feature of web design. In fact, the beginning of the Font Properties section of the CSS1 specification begins with the sentence, Setting font properties will be among the most common uses of style sheets. The intervening years have done nothing to disprove this assertion.

CSS2 added the ability to specify custom fonts for download with @font-face, but it wasnt until about 2009 that this capability really began to be widely and consistently supported. Now, websites can call on any font they have the right to use, aided by online services such as Fontdeck and Typekit. Generally speaking, if you can get access to a font, you can use it in your design.

Its important to remember, however, that this does not grant absolute control over fonts. If the font youre using fails to download or is in a file format the users browser doesnt understand, then the text will be displayed with a fallback font. Thats a good thing, since it means the user still gets your content, but its worth bearing in mind that you cannot absolutely depend on the presence of a given font, and should never design as if you can.

Font Families

What we think of as a font is usually composed of many variations to describe bold text, italic text, and so on. For example, youre probably familiar with (or at least have heard of) the font Times. However, Times is actually a combination of many variants, including TimesRegular, TimesBold, TimesItalic, TimesBoldItalic, and so on. Each of these variants of Times is an actual font face , and Times, as we usually think of it, is a combination of all these variant faces. In other words, Times is actually a font family , not just a single font, even though most of us think about fonts as being single entities.

In order to cover all the bases, CSS defines five generic font families:

Serif fontsThese fonts are proportional and have serifs. A font is proportional if all characters in the font have different widths due to their various sizes. For example, a lowercase i and a lowercase m are different widths. (This books paragraph font is proportional, for example.) Serifs are the decorations on the ends of strokes within each character, such as little lines at the top and bottom of a lowercase l , or at the bottom of each leg of an uppercase A . Examples of serif fonts are Times, Georgia, and New Century Schoolbook.

Sans-serif fontsThese fonts are proportional and do not have serifs. Examples of sans-serif fonts are Helvetica, Geneva, Verdana, Arial, and Univers.

Monospace fontsMonospace fonts are not proportional. These generally are used for displaying programmatic code or tabular data. In these fonts, each character uses up the same amount of horizontal space as all the others; thus, a lowercase i takes up the same horizontal space as a lowercase m , even though their actual letterforms may have different widths. These fonts may or may not have serifs. If a font has uniform character widths, it is classified as monospace, regardless of the presence of serifs. Examples of monospace fonts are Courier, Courier New, Consolas, and Andale Mono.

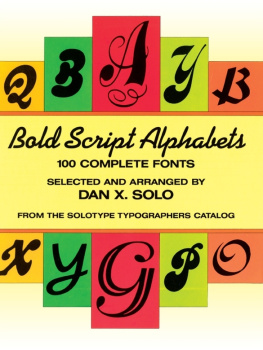

Cursive fontsThese fonts attempt to emulate human handwriting or lettering. Usually, they are composed largely of flowing curves and have stroke decorations that exceed those found in serif fonts. For example, an uppercase A might have a small curl at the bottom of its left leg or be composed entirely of swashes and curls. Examples of cursive fonts are Zapf Chancery, Author, and Comic Sans.

Fantasy fontsSuch fonts are not really defined by any single characteristic other than our inability to easily classify them in one of the other families (these are sometimes called decorative or display fonts). A few such fonts are Western, Woodblock, and Klingon.