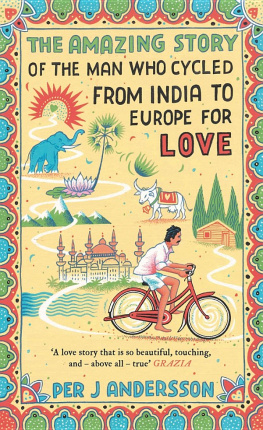

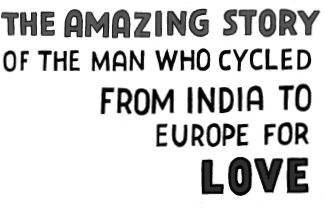

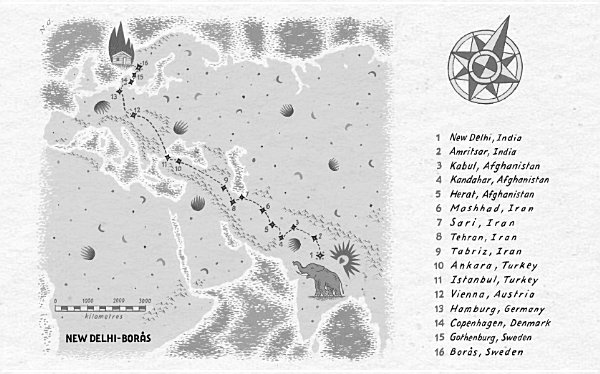

The story begins in a public square in New Delhi. On a cold December evening a young European woman of noble descent appears before an Indian street artist known locally as PK and asks him to paint her portrait - it is an encounter that will change their lives irrevocably.

Contents

The Prophecy

E ver since the day I was born, in a village in the Indian jungle, my life course has been steered by a prophecy.

It was winter and almost time for the New Year celebrations, which remained a tradition, even though the British who had introduced them to our country had left two years earlier. It rarely rained in December, but that year the north-eastern monsoon lingered on the Orissa coast. Eventually the rain subsided, but the forested slopes on either side of the river remained hidden in the dark clouds that doused the landscape in twilight, even though it was morning.

Suddenly, the sun cut through the darkness.

And there I was, laid in a basket inside one of the village huts, destined to be the protagonist of our story although I did not yet have a name. My family gathered around, marvelling at me, fresh to the world. The village astrologer was also present, proclaiming that I had been born under the sign of Capricorn, on the very same day as the Christian prophet.

Look! cried one of my brothers.

What?

There, above the baby!

Everyone looked up and saw a rainbow that had formed in the beam of light that fell through the little window.

The astrologer knew what it meant.

He will work with colour when he grows up.

It did not take long for the rumours to spread around the village. A rainbow child, said one. A great soul, a Mahatma, is born, said another.

When I was only one week old a cobra strayed into the hut where I was sleeping, oblivious to the impending danger. It rose above my cot and flared its muscly hood. My mother saw it and assumed it had already bitten me. She ran to me just as the snake slithered away outside. But I was fine. Indeed, I was lying there quietly, my dark eyes gazing out into the void. A miracle!

The village snake charmer told my parents that the cobra had extended its hood to protect me from raindrops dripping through the ceiling directly above my cot. The rain had been hammering at our roof for the past few days and it was now leaking. Cobras are considered holy and this was a sign from the divine. The astrologer nodded as the snake charmer spoke.

Yes, indeed. I was no ordinary baby.

The astrologer returned to tell my fortune. He took a sharpened stick and scratched my future on a palm leaf. He will marry a girl from far, far away, from outside the village, the district, the province, the state and even the country, it began.

You neednt go looking for her, she will come to you, he whispered to me alone, looking straight into my eyes.

At first, my father could not make out the rest of the words. The astrologer held an oil lamp underneath a candlestick smeared with butter and let the soot that formed fall into the grooves scratched in the porous leaf. The text appeared before my parents eyes. He did not need to read it out loud, my father could see the curly Oriya script for himself and read it to my mother: His futurewife will be musical, own a jungle and be born under the sign of Taurus.

I have lived with the prophecy on the palm leaf and the stories of the rainbow and the cobra ever since I learned to understand what the adults were saying. Everyone was sure my future had been set.

I was not the only one to have my future told. The fates of all children are written in the stars the moment they are born. That is what my parents believed, and so did I, growing up.

And in some ways, I still do.

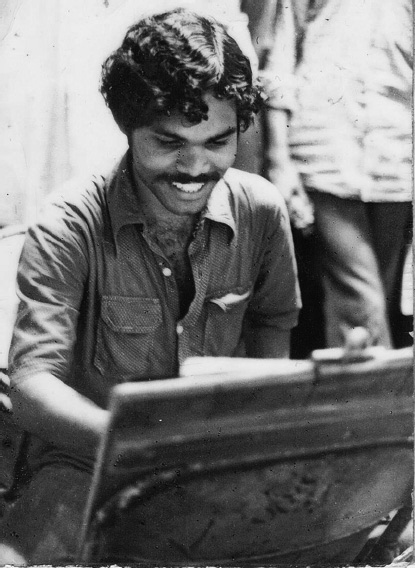

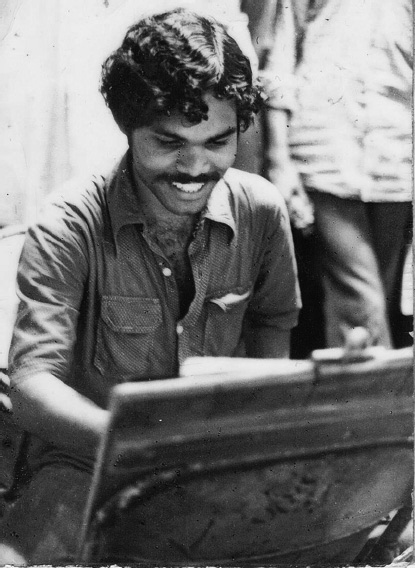

H is full name is Jagat Ananda Pradyumna Kumar Mahanandia.

A joyful name. Jagat Ananda means universal happiness, and Mahanandia means optimism. But this is not his full name; this is just the short version. Including all the titles passed down from grandparents, tribe and caste, it runs to 373 letters.

But who can keep track of 373 letters? His friends settled instead on two. P (for Pradyumna) and K (for Kumar). PK.

PKs family never used any of his given names when they called out after the little boy as he ran through the village or climbed up high in the mango trees. His father used Poa, meaning little boy, his paternal grandparents always said Nati, grandson, and his mother chose Suna Poa, golden boy, because his skin was just a shade lighter than that of his siblings.

His first memories of the village by the river on the edge of the jungle were from after he had turned three. Or maybe he was four. Or still only two. Age was not so important. No one cared about birthdays. If you asked the villagers how old they were, their answers would vary and were never precise. Around ten, forty-something, nearly seventy, or merely young, middle-aged, very old.

However old he was, PK remembers standing inside a house with thick walls made of mud and a roof of yellowed grass. The picture comes into focus. Fields of corn with their dusty tips rustling in the evening breeze and clumps of trees with their plump leaves set alight by flowers in the winter and heavy with syrupy fruit in the spring. A stream flowed through the village and into a large river, behind which a solid wall of foliage and branches rose up from the ground. It was the beginning of the jungle, from which came the occasional trumpeting of an elephant or the growl of a leopard or tiger. Wild animal tracks could often be spotted in the mud, along with piles of elephant dung or the imprint of a tigers paw, accompanied by the buzz of swirling insects and the singing of birds.

PKs horizon was the edge of the jungle, but his universe extended beyond it and into the woods. The village and the jungle. There was nothing else. The forest was endless, mysterious, secret, but also familiar and safe. It was an adventure and yet also a certainty, a comfort. The city was somewhere he had heard about but had never seen for himself.

He lived in the hut with his mother, father and two older brothers. And his fathers parents, of course. That was how most families lived; tradition dictated that the oldest son stayed with his parents, even after he had married and started his own family. Shridhar, PKs father, held fast to those traditions.

PK did not often see his father. He worked as the postmaster in Athmallik, the nearest town, which had markets, teashops, a police station and a jail. As the twenty-kilometre journey was too far to cycle every day, his father had a room with a bed at the post office where he slept during the week. Every Saturday night he would make the journey home with PKs two older brothers, who lived in the towns boarding school.

PK felt like an only child. During the week his mother devoted all her attention to him. Most days it was just the two of them and his grandparents in the house in the village on the edge of the forest.

Next page