PREFACE

In Londons Kings Cross, deep in the vaults of the British Library, there exists another world. It is minute and perfectly round, gold-flecked and held in Gods almighty grace, and it is yours for an hour if you order it by the counter. One spring day I sit in the hushed halls, looking for this world in a Kindle-sized book, turning page after crisp page stained with the nicotine of time. Manuscripts rustle behind me and a keyboard clicks in the distance, and suddenly, there it isa thirteenth-century map, vast in its smallness; Asia on top, Jerusalem in the middle, Europe and Africa down below. The African corner hosts a menagerie of monstrous figures, headless and dog-faced, kept in a neat line of pens touching the very margins of the known world. In their opposite corner, in Asia, a wall circles the abject lands of Gog and Magog, cannibalistic races locked up until Judgment Day. Christ stands guard above it all, golden-aurad and hands aloft, while dragons lurk below. This medieval world is navigable like a London Underground mapa perfect circle of Christian knowledge in which monsters squat at the margins, held in Gods delicate grip like the page between my fingers.

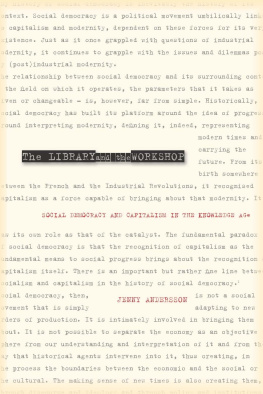

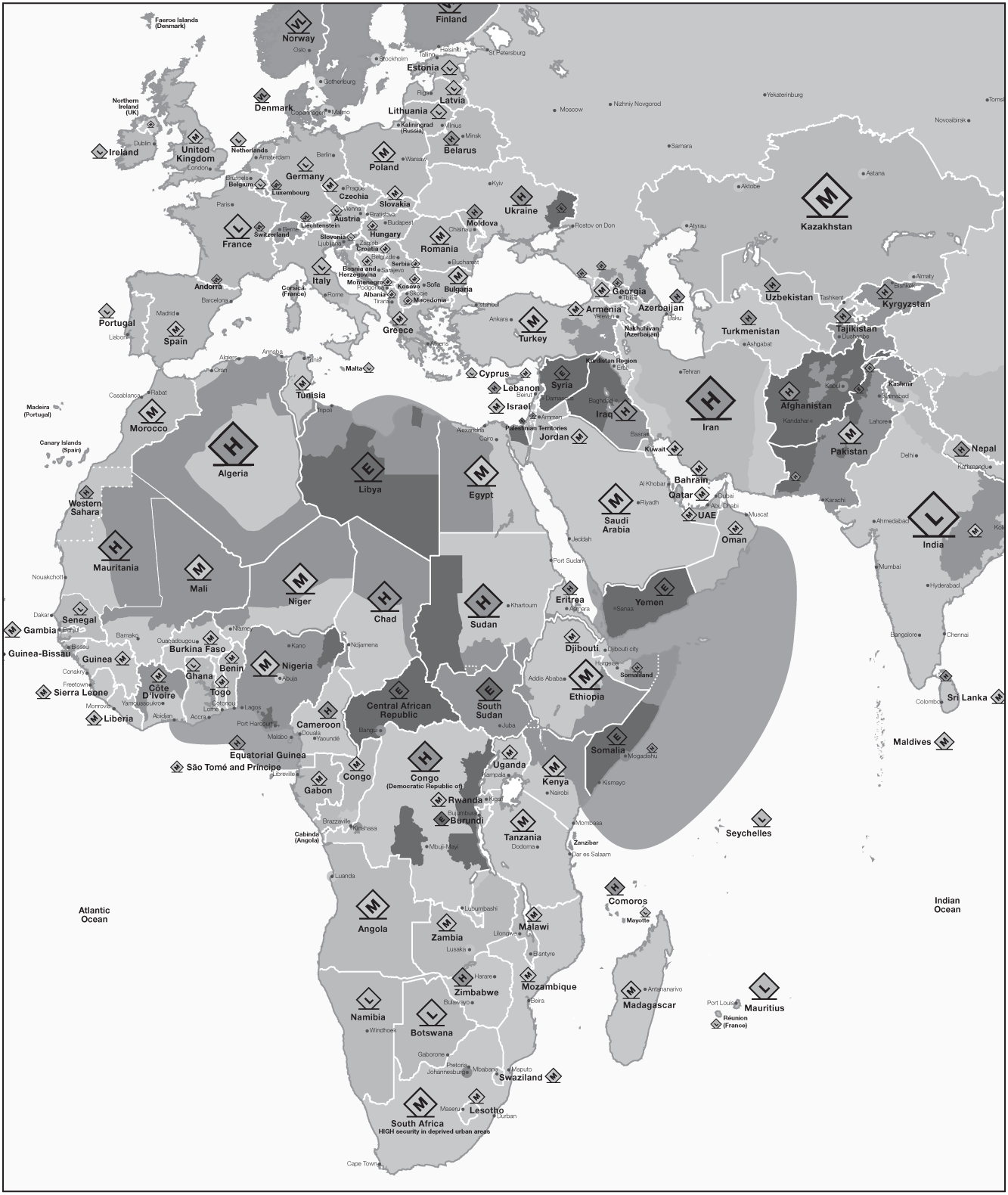

A few stops down the Tube from my British Library hall lies the Cottons Centre, a corporate monolith with high-spec views across the Thames to the City of London. There, suited risk analysts are busy building a digital map for the twenty-first century, navigable not for Christs pious followers but for big business. Their world is not shielded by divine hands or flecked with gold; instead it is painted in shades of risk, from light green to wine-red. Unlike its medieval counterpart, the Risk Maps margins are safe and pale while its central zones are slathered with the deep reds of danger, from the Sahara to Tigris to the Hindu Kush. Zoom in and you will see the red blots bleeding outwards, encroaching on the Mediterranean and trickling toward Texas, like pools of blood gathering at a shuttered door. On the Risk Map there are no visible monsters, no Christ to contain them, and no walls or cages to keep them at bay: instead they roam wild and unseen, spreading their beastly trace as they move.

Map 2. Detail from the World Risk Map 2018, by Control Risks, the specialist risk consultancy. Color codes indicate level of security risk; labels indicate level of political risk. For full color version, see www.controlrisks.com/riskmap-2018 Control Risks.

This is the story of our world of encroaching danger, of why it bleeds, and of what we may do to stop it being stained by scarlet shades of fear.

INTRODUCTION

INTO THE DANGER ZONE

Beyond the bar glittered the dark Atlantic. Beer bottles clinked in the African night breeze as expats danced to the booming tunes of a European DJ under a canopy. In the crowd of artists and hangers-on, French culture buffs and curators in expensive shawls mingled with lanky Senegalese painters and smart-shirted Western aid workers, the stalwarts on Dakars international scene. It was May 2014 and the art biennale had come to the Senegalese capital, bringing a well-needed party to the very edge of West Africa. For out there, beyond the chatter and champagne, lurked a different reality: the vast hinterland of the Sahel and the Sahara, where in the past few years the onetime music festivals had packed up and their swirling desert blues had ceased to reverberate.

Paco Torres stood, wild-haired with beer in hand, in our awkward aid worker clique at the bar. up like a childs. It was the adventurer aura that did it, he explained while recounting an earlier venture up the Niger River to conflict-racked northern Mali, skirting roadblocks and recalcitrant soldiers. Now Paco was mulling a trip into northern Nigeria, an area where Boko Haram had just kidnapped more than two hundred schoolgirlsand where, as one Dakar-based aid chief told me, If your complexion is anything less than a Nigerians, you wont really be going. All trips were at Pacos own expense and risk. Now is the first time ever that I can afford insurance, he said, though on second thought he was not sure whether it covered his risk-filled escapades. His pay from Spanish dailies remained miserly, but at least he was now their voice from West Africa, covering disease and disaster, terror and conflictthe four horsemen of the Apocalypseplus Senegalese wrestling shows and much else thrown in for good measure.

Im not a war correspondent, Paco insisted as he downed his beer. Im really a journalist of peace. As the DJ played away into the Dakar breeze at the biennale party, he lingered at the far edge of the canopy, his mind yet again scheming for the next trip. Unlike most of the Dakar expats around usand much like one of the early colonial explorers in whose footsteps he was treadinghe longed to roam the hinterland and the far-flung no go zones of our new, fearful era.

Look at the world today. Switch on Google Maps on your smartphone and search for Timbuktu, that onetime epitome of remoteness, and you will get car directionsthree days and fourteen hours from my Oxford home via the N-6, on a route that has tolls, includes a ferry, and crosses through multiple countries, as the app helpfully informs me. You can browse geo-positioned images from northern Nigeria and the Libyan desert, or get customers restaurant recommendations for Quetta in the Pakistan-Afghanistan borderlands, a town I once crossed on my way to India (apparently, for a tandoori treat, dont go here: Usmania at Pishin stop SUCKS. Their service is bad, prices unreasonable and food tastes horrible). In fact, dont go to any of these placesnot if you are a white Westerner, at any rate. These sites are all off limits; they are reblanked parts of the map at a time of disorderly globalization.