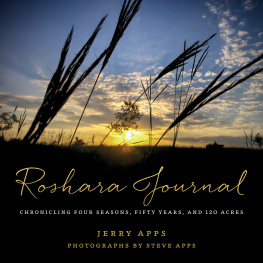

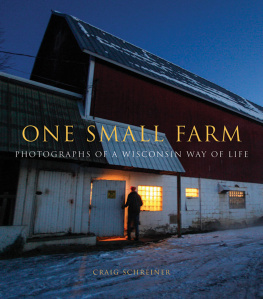

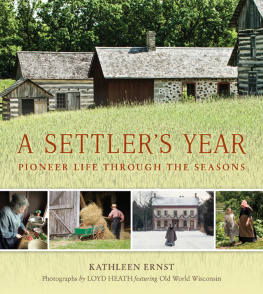

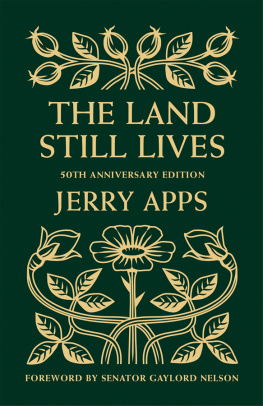

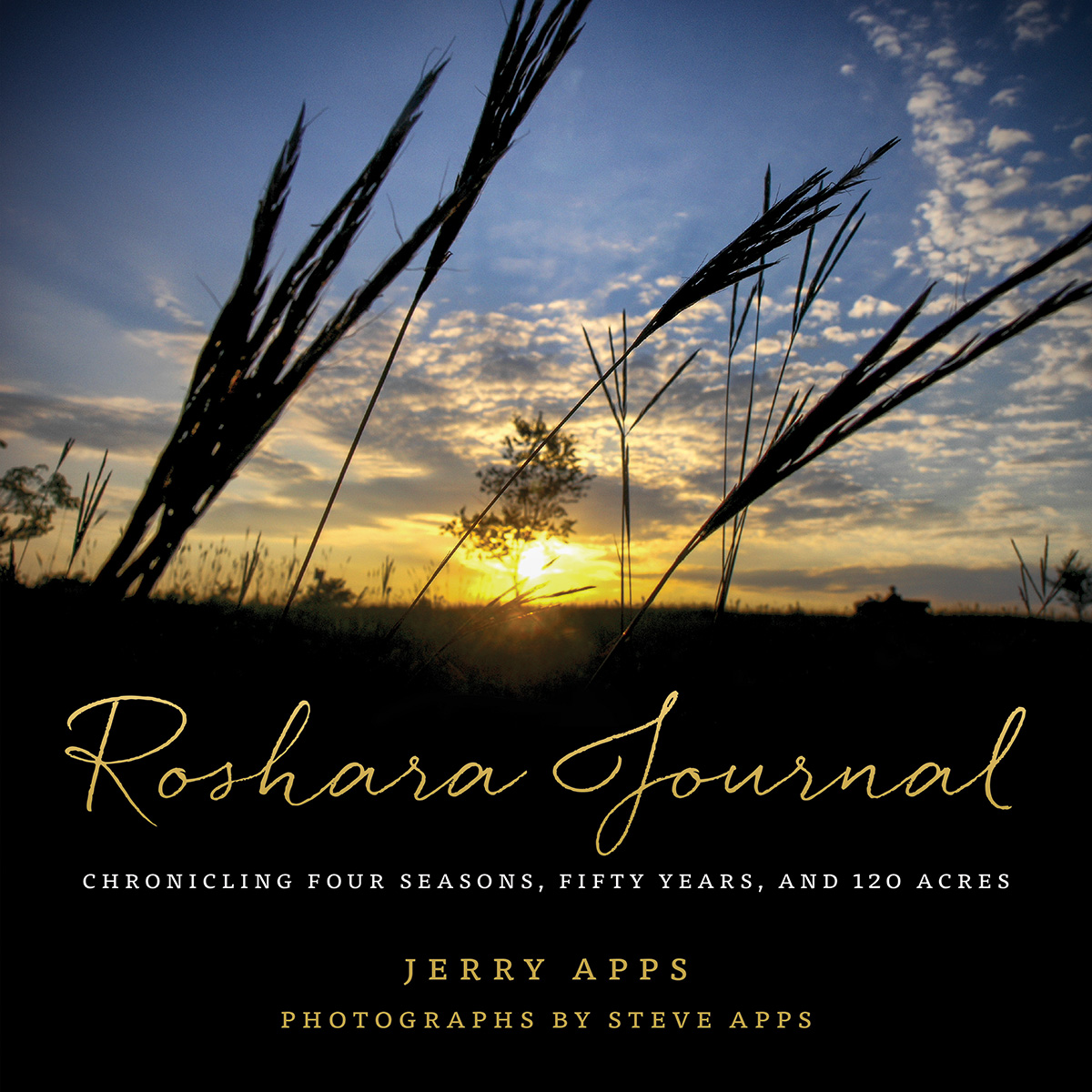

Roshara Journal

CHRONICLING FOUR SEASONS, FIFTY YEARS, AND 120 ACRES

Jerry Apps Photographs by Steve Apps

WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

The Wisconsin Historical Society helps people connect to the past by collecting, preserving, and sharing stories.

Founded in 1846, the Society is one of the nations finest historical institutions.

Order books by phone toll free: (888) 999-1669

Order books online: shop.wisconsinhistory.org

Join the Wisconsin Historical Society: wisconsinhistory.org/membership

Text 2016 by Jerold W. Apps

Photographs 2016 by Steve Apps

E-book edition 2016

For permission to reuse material from Roshara Journal (ISBN 978-0-87020-763-1; e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-764-8), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.Designed by Percolator Graphic Design

20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5 | Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Apps, Jerold W., 1934 | Apps, Steve. Title: Roshara journal : chronicling four seasons, fifty years, and 120 acres / Jerry Apps ; photographs by Steve Apps. Description: Madison : Wisconsin Historical Society Press, [2016] Identifiers: LCCN 2015042398| ISBN 9780870207631 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780870207648 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Farm lifeWisconsinWaushara County. | Farms WisconsinWaushara County. | Country lifeWisconsinWaushara County. Classification: LCC S521.5.W6 A665 2016 | DDC 636.009775/57dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015042398 |

Contents

Introduction

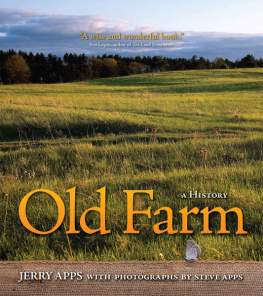

Ive kept a journal since I was twelve years old, so when Ruth and I bought a farm in central Wisconsin in 1966, I naturally began jotting down our experiences on this worn-out, hilly, stony and sandy land (not much of a farm, one neighbor called it). Our children were two, three, and four at the time, so this has been a shared family adventure from the beginning, one that continues to this day.

We named our farm Rosharacombining the township name where the farm is located (Rose) with the county name (Waushara). As weve spent nearly fifty years here restoring the land to something like it was when it was first settled in 1867, we have seen many changes, and, I hope, several improvements. We are in the process of restoring a six-acre farm field to prairiewith a strategy that mainly consists of standing back and letting nature take its course. Each year we welcome the wildflowers and grasses, whose histories go back to presettlement days. We help them along by removing rogue trees and brush and mowing the prairie so the native plants have access to light and soil nutrients. But weve done no planting of wildflowers or grasses. This approach to restoration does not provide quick results, nor do I expect them. One of the many things I have learned from my connections to nature is patience.

A year after buying Roshara, I found a small patch of lupines growing on a hillside on the south side of the farm. With the clearing away of brush and nonnative trees, the lupine patch has grown to cover about three acres. As the fragrant, showy lupines have flourished, so have the endangered Karner blue butterflies that depend on them for their existence.

We have encouraged a self-seeded white pine plantation that grows on five acres of former cornfield. In the 1930s, a previous owner of this land planted a row of white pine along the western border of the field to stop wind erosion; it is those trees, some of them giants now, that provided the seeds for the new plantation. Our self-seeded pines, thinned once ten years ago, now stand more than forty feet tall, a reminder of the white pines that were native to central and northern Wisconsin. Its been amazing to see the transformation from cornfield to pine plantation happen without any help from anyone.

Weve also planted several thousand trees here, mostly red pine, hand-planting one thousand trees every year during our early years of ownership and machine-planting about seven thousand in 2010. Weve tried valiantly to prevent the spread of some undesirables, such as black locust trees, which spread like wildfire and grow like the worst weeds on the farm. With the help of a consulting forester, we are slowly winning the black locust battle. But the fight with buckthorn continuesanother invasive that spreads rapidly in our shady oak woods.

We maintain a large vegetable garden that now provides three families with fresh-picked lettuce, tomatoes, potatoes, green beans, broccoli, and much more. It is in the garden perhaps more than any place on this old farm that I have taught my children and grandchildren about nature, about where the food they eat comes from, and about working together. As a family we have planted, weeded, and harvested together, and weve enjoyed many meals together featuring vegetables that we have grown.

Our 120 acres includes one pond, which we call Pond One, and half of a second pond, Pond Two. Wetlands embrace each of these three-acre seepage ponds, providing habitat for an abundance of wildlife and plants. Canada geese, sandhill cranes, and several duck species nest at the pond, accompanied by hundreds of frogs, turtles, and other aquatic creatures. We also see raccoons and occasionally a coyote, a fox, or even a bear sneaking around one of the ponds.

The ponds change with the seasonshigher in spring, lower in midsummer, and somewhat higher again with the fall rains. They have also changed dramatically over the years. When we bought the farm in 1966, the ponds were low. By the early 1980s they were the highest I have seen them, running over their banks and creating sizeable lakes. The water levels began falling in the late 1990s and have never come close to what they reached in the 1980s. Snow and rainfall amounts surely make a difference in the pond levels, but I am also confident that the amount of farm irrigation occurring in our township has an effect, as irrigation pumps draw millions of gallons of water from the aquifer that underlies our land. When the water table is high, our ponds are filled. When the water table drops, so do our pond levels.