HIDDEN

HARMONIES

THE LIVES AND TIMES

OF THE

PYTHAGOREAN THEOREM

ROBERT KAPLAN AND

ELLEN KAPLAN

Illustrations by Ellen Kaplan

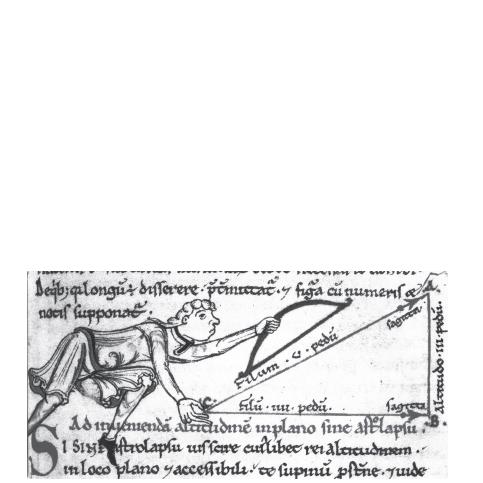

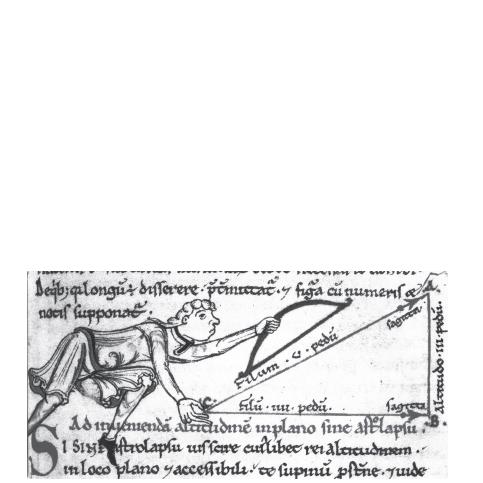

Larc et la fleche

Mesure du carr de lhypotenuse

Mont-St-Michel 12th century

FOR

BARRY MAZUR

A hidden connection is stronger than an apparent one.

HERACLITUS

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

The Mathematician as Demigod

CHAPTER TWO

Desert Virtuosi

CHAPTER THREE

Through the Veil

CHAPTER FOUR

Rebuilding the Cosmos

CHAPTER FIVE

Touching the Bronze Sky

CHAPTER SIX

Exuberant Life

CHAPTER SEVEN

Number Emerges from Shape

CHAPTER EIGHT

Living at the Limit

CHAPTER NINE

The Deep Point of the Dream

CHAPTER TEN

Magic Casements

AFTERWORD

Reaching Throughor PastHistory?

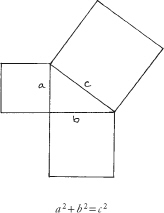

Man is the measure of all things. While Protagoras had the moral dimension in mind, it is also true that we are uncannily good as physical measurers. We judge distancesfrom throwing a punch to fitting a beamwith easy accuracy, seeing at a glance, for instance, that these two lines

add up to this one:

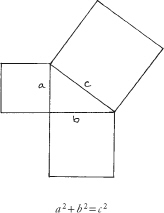

Whats odd is that we are much less accurate at estimating areas. How do the combined areas of these two squares:

compare to the area of this?

Its hard to believe that they are the samewhich is why the Pythagorean Theorem is so startling:

Where did this insight come from and how do mathematical insights in general surface? How did the tradition evolve of measuring the worth of our insights by proofs, and what does this tell us about people and times far distant from oursyet with whom we share the measures that matter?

We share with them too the freedom of this shining city of mathematics, looking out where we will from its highest buildings or in astonishment at the imaginative proofs that support them, made by minds for minds. You can safely no more than glance at these proofs in passing, knowing they wait, accessibly, for when you choose to explore their ingenious engineering.

Come and see.

CHAPTER ONE

The Mathematician as Demigod

The Englishman looked down from the balcony of his villa outside Florence. Guido, the peasants six-year- old son, was scratching something on the paving- stones with a burnt stick. He was inventing a proof of the Pythagorean Theorem; what we remember as the algebraic abstraction a2 + b2 = c2 he saw as real squares on the sides of a real triangle

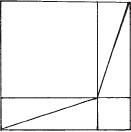

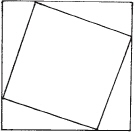

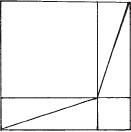

Do just look at this. Do. He coaxed and cajoled. Its so beautiful. Its so easy. And Guido showed the Englishmans son how the same square could be filled with four copies of a right triangle and the squares on its sides,

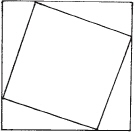

or the same four triangles and the square on the hypotenuse

so that the two squares of his first diagram must equal in area the one square in the second.

And the Englishman thought of the vast differences between human beings. We classify men by the colour of their eyes and hair, and the shape of their skulls. Would it not be more sensible to divide them up into intellectual species? This child, I thought, when he grows up, will be to me, intellectually, what a man is to a dog. And there are other men and women who are, perhaps, almost as dogs to me.

But the child never grew up: he threw himself to his death in despair at being snatched from his family by a well-meaning signora, who forced him to practice his scales and took away the Euclid that the kind Englishman had given him.

A true story? Emphatically not. It is Aldous Huxleys Young Archimedes,

The falsity of this story isnt just in Huxleys having patched it together from what he had read in Heath, and from the legend of the brutal centurion who, sent to fetch Archimedes, killed him instead, because he wouldnt stop drawing his diagrams in the dirt. Huxleys story is much more deeply false: false to the way mathematics is actually invented, and false to the universality of mind. The picture of super-humans in our midstliving put-downs to our little pretensions, yet testimony to more things in heaven and earthis certainly dramatic, but the actual truth has greater drama still, woven as it is of human curiosity, persistence, and ingenuity, with relapses into appeals to the extraterrestrial. How this truth plays out is the story we are going to tell.

A touch of taxes makes the whole world kin. Around 1300 B.C., Ramses II (Herodotus tells us) portioned out the land in equal rectangular plots among his Egyptian subjects, and then levied an annual tax on them. When each year the flooding of the Nile washed away part of a plot, its owner would apply for a corresponding tax relief, so that surveyors had to be sent down to assess just how much area had been lost.

This gave rise to a rough craft of measuring and duplicating areas. Perhaps rules of thumb became laws of thought among the Egyptians themselves; in any event, such problems and solutions seem to have been carried back by early travelers, for this, in my opinion, Herodotus says, was the origin of geometry [literally land-measure], which then passed into Greece.

Did their rules, long before Pythagoras, include the theorem we now attribute to him? For Egyptian priests claimed that he, along with Solon, Democritus, Thales, and Plato, had been among their students. Whoever believes that all things great and good should belong to a Golden Age, and that Egypts was as golden as its sands, would like to think so. But a theorem is an insight shackled by a proof (such as Guidos) so that it wont run away, and not the least line of a proof has been found on Egypts walls or in its papyri. Well, but might they not have had the unproven Insight, which would have been glory enough?

Next page