Published by TAJ Books International LLC 2013

219 Great Lake Drive

Cary, North Carolina, USA

27519

www.tajbooks.com

www.tajminibooks.com

Copyright 2013 TAJ Books International LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher and copyright holders.

All notations of errors or omissions (author inquiries, permissions) concerning the content of this book should be addressed to .

ISBN 978-1-84406-251-5

Printed in China

1 2 3 4 5 17 16 15 14 13

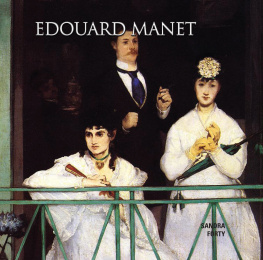

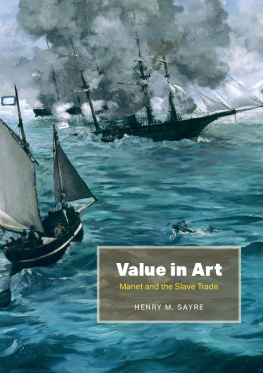

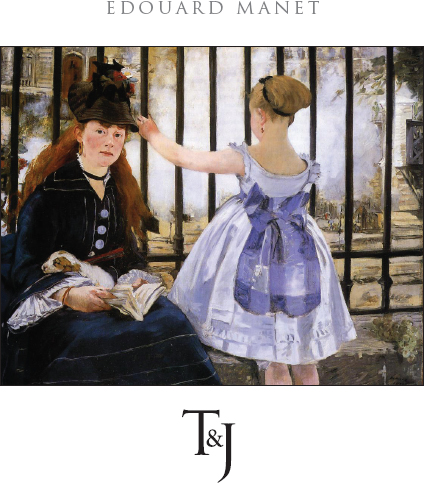

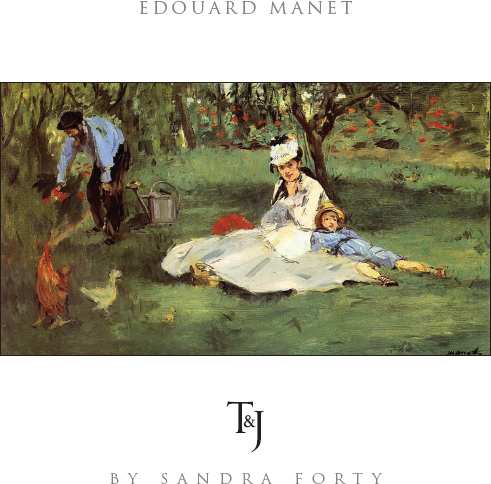

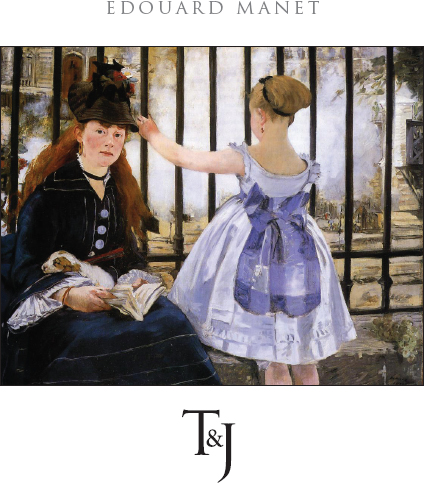

EDOUARD MANET

18321883

M any art historians believe Edouard Manet is the father of modern art. Although often cited alongside the Impressionists, he was not a member of their group and never exhibited in their Salon des Rfuses. Instead, he pioneered a path between realism and impressionism, choosing contemporary subjects and composing them in a truly modern fashion. By doing so he became a controversial painter, offending critics who considered that art should follow the traditional established precepts of technique, subject, and composition, and being applauded by the (generally) younger audience who was excited by his new vision and approach to the medium.

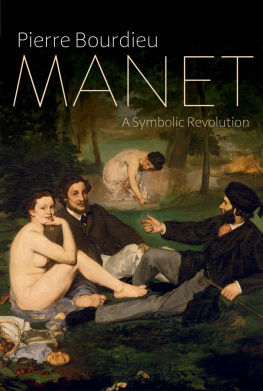

Many of Manets paintings provoked outrage and scandal but his most controversial work was Le Djeuner sur lHerbe (Luncheon on the Grass), which showed a naked woman enjoying a picnic beside two fully and conventionally, if rather exotically, dressed men. Today it is hard to appreciate the shock it caused, but at the time the painting became a real cause clbre.

Manet was particularly inspired by the Spanish realism of Velzquez, who he idolized and called the painter of painters, and other 17th century artists such as Bartolom Murillo. He particularly admired the way they showed ordinary street people and the poor urban workers of the slums and back streets without exhibiting judgment or romance about their subjects circumstances. Consequently, about half of his output was scenes of his fellow Parisians going about their daily lives in the city. His early style was influenced by the realism of Gustave Courbets loose brush strokes and simplified details. While he was learning his trade he painted the usual topics of mythological, historical, and religious subjects but after he developed his own style he rarely returned to such conventional ideas.

Manet became one of the first artists to make the common man (and woman) the theme of his work. His preferred subjects were compositions of people enjoying their leisure time in the parks, cafs, and amusement centers around Paris. He also liked his subjects dressed in unexpected outfits, a quirk that many observers found distinctly peculiar. The Impressionists, with whom he became close friends, found his work inspiring and continually tried to get him to exhibit alongside them at their exhibitions but he never did. Like many of his contemporaries, Manet was influenced by the major Japanese artists of the day and the unusual compositions and use of flat color of their woodblock prints.

Manet lived and worked at a very exciting time in terms of politics and art. He counted many of the great names of French late-19th-century culture among his friends, many of whomsuch as Stphane Mallarm, Antonin Proust, and Emile Zolahe painted. Portraits of his family and friends were also numerous among his works.

Self-portrait with a palette, 1879

The Paris Salon was the arbiter of acceptable art. The Salon hung an annual government-sponsored exhibition of contemporary paintings chosen by a jury of wealthy and influential art critics who decided what was good enough for exhibition and rejected the rest. Their taste was alarmingly conventional and they were heavily resistant to modernism and change. Manet ached to be acknowledged as a great artist, but to do so he had to be accepted by the entrenched art establishment. Nevertheless, he insisted on being taken on his own terms, not theirs, and waged a career-long battle with the Salon. By the end of his career, he had mixed success. The Salon accepted some paintings and rejected others, but he was determined to prevail and although occasionally discouraged was persistent in his attempts to get his works hung in the annual exhibit. Manet said, The attacks of which I have been the object have broken the spring of life in me people dont realize what it feels like to be constantly insulted.

One of Manets pioneering techniques is called alla prima in which he placed the color he wanted directly onto the canvas instead of building up layers of tints. This technique was particularly effective when painting en plein air and trying to capture a fleeting sunlit scene or light effect. His approach to painting was taken up by the Impressionists, for whom he became rather a hero. The Impressionists too were trying to capture the passing, fleeting moment in a flurry of quick brush strokes. Similarly, many of Manets works are almost photographic in their composition and use of light. As a result, these works had a distinctly modern look for that time, which unnerved critics and alarmed contemporary audiences but inspired the admiration of young, upcoming artists.

Manet, however, preferred working in his studio to being outside. His works are characterized by their solid construction and unorthodox, flat schemes of clear color. A frequent comment about his paintings was that they were too sketchy, showing a loose technique that was thought to lack academic rigor and which many described as crude. As he said, There are no lines in nature, only areas of color, one against another. Unlike the Impressionists, he made frequent and deliberate use of black and other dark pigments. He is said to have remarked black is not a color, yet for his purposes he used it liberally and dramatically.

Compositionally Manet did not reject the historical traditions of his predecessors, but instead updated them with contemporary realities. Despite the comfort of his relative wealth, Manet was still eager to achieve acceptance as an artist and would drop into bouts of depression when his paintings were harshly criticized. In January 1865 he became so dispirited that he even destroyed a couple of his paintings.

Edouard Manet was born on January 23, 1832, at 5 rue des Petits-Augustins, Paris, into an affluent and politically well-connected family. His father, Auguste Manet, was a French judge who confidently expected his son to follow him into the law. His mother, Eugnie-Desire Fournier, was the daughter of a Swedish diplomat and the goddaughter of crown prince Charles Bernadotte of Sweden. They had two more sons, Eugne and Gustave.

During his conventional education the young Manet was frequently taken to the Louvre by his maternal uncle, Edmond Fournier, who enjoyed his nephews interest in art. In 1845 Uncle Edmond encouraged his nephew Edouard to enroll in a dedicated drawing class at the Collge Rollin to refine his technique. While there Manet met his lifelong friend, Antonin Proust, who in time became a respected journalist and politician as well as the French Minister of Fine Arts.

From an early age, Manet was much more passionate about art than his school studies, but to please his father at the age of 16 he agreed to apply to attend the Naval Academy. When he failed the entrance exam he joined the cargo ship Havre et Guadeloupe as a student pilot and sailed to Rio de Janeiro in 1849. The appointment was entirely designed to teach affluent young men how to pass the Academy exams and was not an arduous job. Manet frequently wrote home and in one letter to Eugne said, I dont expect to pass the exam this year. There are even more distractions on board a ship than there are on land. He predicted correctly and failed a second time a few years later.

Next page