Forever on the mountains of their dreams.

Contents

Most of the world came to know David Sharp because

Along the highway of rope that leads above 8,000 meters

One day, the year before his trip to the Himalaya,

If anyone understood what drove Nils Antezana up to the

At the Moment Gustavo Lisi Was Contacting His Mother and

Nils had told his family little about his guide for

It was the busiest week of the Everest season, so

Fabiolas fingers moved frantically over the keyboards on her laptop

For spectators of the mountaineering arena, the summit of Mount

While Damian Benegas was tracking down climbers who might have

Two days after Fabiola and Davide checked into the Yak

Climbing teams on the worlds highest mountains move like yo-yosclimbing

At 21,500 feet, Advanced Base Camp on the Chinese side

On most mornings, climbers on the steep headwalls atop the

Our days back in Base Camp should have been relaxing.

It took me six hours to climb the snow slope

While the rest of the climbers in our camp were

Two days after Georges announcement that our team didnt have

When Gustavo finally arrived at the Yak and Yeti with

The morning after Gustavo told Fabiola about leaving her father

Fabiola was in touch with Tom and Tina Sjogren, at

Some 400 people had attended Nils Antezanas memorial service on

After Nilss death, Fabiola and Davide decided to move from

The link on EverestNews.com was irresistible.

In 2004, David Sharp and I had each vowed that

Soon after I sat down to talk with Gustavo Lisi,

KATHMANDU, NEPALMARCH 28, 2006

M ost of the world came to know David Sharp because of how desperately late he was. I got acquainted with him because he was on time.

Sams Bar at seven. During the last days of March 2006, the words were a mantra among the group of climbers I would join on Mount Everest through the next two months. The small terrace bar in the Thamel section of Kathmandu was a warm refuge, both from our visions of the frozen mountain a hundred miles away and from the crazed, carnivalesque streets below. Most of us, wrapped up in our preparations for the climb, didnt get to Sams until seven thirty or eight. But on the days that he joined us, David was there right on time, as was my wife, Carolyn, and on one occasion, me.

As we waited for the rest of our dinner crew, David said that once he knocked Everest off his list, he was probably going to give up mountaineering.

Im thirty-four years old. I want to go home, meet someone, settle down, and have children.

I guess I might climb on weekends, he said, but he sounded doubtful.

It was Davids third time on the mountain; my second. We were both more than familiar with the weeks of frigid suffering that lay before us, and I wondered how David could fire himself up for the long, cold climb with such a lukewarm attitude toward the sport he once loved.

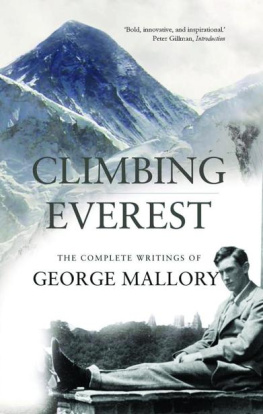

He was six feet tall and thin, with wire-rimmed glasses, a big-toothed grin, and a barely there goatee that got scruffier on the mountain. The Guisborough, England, native had given up his job as an engineer to climb, but was starting a new career as a math teacher in the fall. He carried two books with hima collection of Shakespeare in honor of George Mallorys readings of King Lear and Hamlet on the mountain eighty-two years before, and, although he claimed he was an atheist, a Bible. He brought only a disposable camera to record his trip.

Ive got all the photos I need, he told companions in Base Camp. Except for the summit.

If he didnt make it to the top this time, he said, he wasnt coming back. He couldnt afford to. As it was, he had barely scraped up enough money for his current climb. He didnt have the cash to hire any Sherpa support, and had purchased only two bottles of oxygen for a climb on which most people use five or more. Two years earlier, on his second attempt, he had tried to climb without oxygen, but carried two tanks of gas with him just in case. He became so hypoxic, he told us, that he forgot to use them when it became apparent he wouldnt top out without them. Forced to retreat, he finally remembered the oxygen cylinders and took them out of his pack, put them down in the snow and, despite their value of nearly $900, walked down without them. His botched summit bid cost him more than the oxygen: He lost his left big toe and part of another to frostbite. But he laughed at the memory and said that he was willing to lose more digits to make his final attempt on the peak pay off.

Still, even though he was climbing solo, he had told his mother before he left England that if he got into real trouble, he could count on some help.

On Everest you are never on your own, she would recall his telling her. There are climbers everywhere.

The mountaineers I learned the ropes with would have honored David with the title dirtbag, for bringing only what he thought he absolutely needed to survive, and part of me admired his bare-bones approach to the climb. But though I had once put together my climbs the same way, we now had little in common.

Instead of the scriptures, Shakespeare, and a cardboard camera, I had plenty of booksboth for reference and entertainmentand six cameras, along with three laptops, a satellite modem and satellite phone, a DVD burner, external hard drives, two digital voice recorders, a minidisc recorder, an iPod, portable speakers, and dozens of notebooks. Carolyn brought three video cameras. All of that was on top of the ice axes, crampons, down clothes, Frankenstein-size boots, and the rest of the Everest climbers wardrobe.

I was loaded for bear, and I had been the last time we were in the Himalaya as well. In 2004, I reported live from the mountain for The Hartford Courant newspaper, covering the Connecticut Everest Expedition, a team with which I was also climbing. As I left for the Himalaya that March, I was convinced I was prepared for the endeavor ahead. But by the time I reached the mountain, I knew I was wrong. As it turned out, so was David.

O n May 14, 2006, six weeks after our last dinner together, David Sharp came upon a corpse in a cave high on Everest and sat down beside it. Its believed, but not certain, that David had reached Everests summit that afternoon, climbing on the mountains northeast ridge in Tibet, the same route he had used to make his previous two attempts on the peak. It was quite late, in Everest climb time, and probably already dark when David, the last person out above the highest camp in the world, arrived at the tiny, jagged grotto. The dead man he sat next to, nicknamed Green Boots, was an Indian climber who had resided for a decade inside the concrete-colored and crypt-shaped hole in a wall of overhanging limestoneGreen Boots Cave. Orange, black, and blue oxygen tanks were strewn among the fractured stones at the entrance to the small roomscrap metal along a highway to the top of the world. Davids two bottles of oxygen were almost certainly exhausted; he had been climbing for some twenty hours straight. Hed had no partner joining him on the ascent, or at any other time during his expedition. Instead he had signed on to the permit of an international teama random group of climbers from around the world brought together only by their need to save money by sharing base camp facilities. David had no radio or satellite phone to communicate with the other independent climbers sharing his permit, or the more than thirty other teams in the lower camps. He was about as alone as a person can be on what has become a very crowded mountain. Still, its hard to imagine that he didnt, at some time when he was approaching the cave, believe that he was in the homestretch to the rest of his life. He was less than 1,000 vertical feet away from Camp Three, where his own tent or other climbers could have provided everything he needed to survive the nightexcept the will to do it.