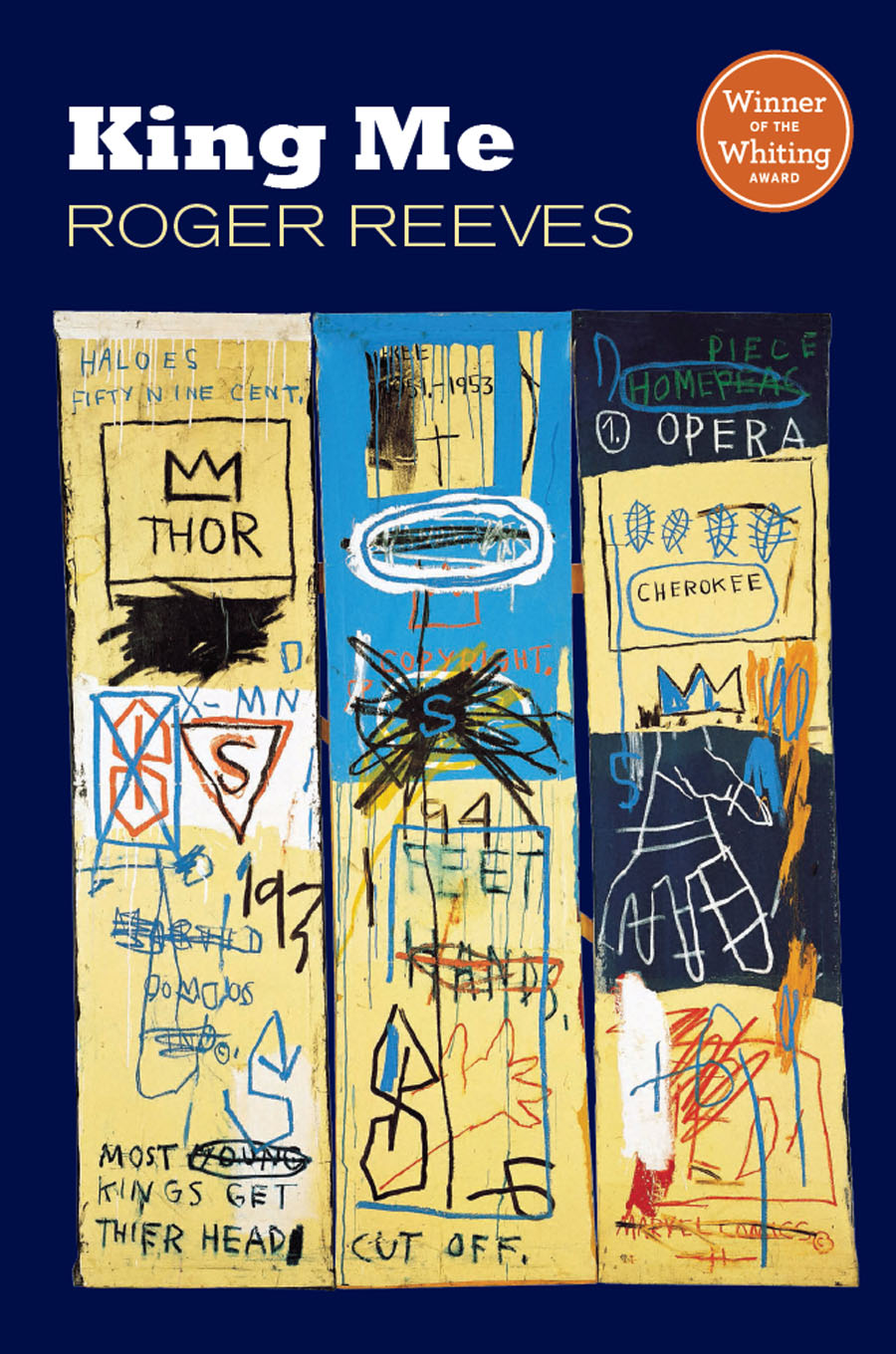

Copper Canyon Press encourages you to calibrate your settings by using the line of characters below, which optimizes the line length and character size: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Pellentesque eui Please take the time to adjust the size of the text on your viewer so that the line of characters above appears on one line, if possible. When this text appears on one line on your device, the resulting settings will most accurately reproduce the layout of the text on the page and the line length intended by the author. Viewing the title at a higher than optimal text size or on a device too small to accommodate the lines in the text will cause the reading experience to be altered considerably; single lines of some poems will be displayed as multiple lines of text. If this occurs, the turn of the line will be marked with a shallow indent. Thank you.

We hope you enjoy these poems. This e-book edition was created through a special grant provided by the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. Copper Canyon Press would like to thank Constellation Digital Services for their partnership in making this e-book possible. For my people everywhere Table of Contents

Guide

Pledge I, Roger Reeves, hereby pledge that I will not come back to this city, if this city will not come back to me. I leave the children waving their flags and wrists at a dark sky, without worrying about the coconut tree dropping its wintered fruit upon their heads. I leave the man with his one leg turned backward to walk this street twice as pure contradiction.

I leave the heron on the roof, the dachshunds scrambling over the cobblestone in their black patent-leather shoes, and the flies to open wide and swallow as much melon as they can before evening comes and that same melon is between my lips. I leave puddles at the end of driveways and in them, to float, tiny fronds of a flower that I cannot name but the woman beside me can. I leave the fresh bread in wire baskets and the old women to point at the rolls they wish to place in their mouths. I leave the opera house, its green domes draped in gold, the cobbler and his glue, the mechanic and his belly, and yes, I leave rain to wash every bare foot in this city. I leave the childrens thirst on the metro next to a pink pen that no longer holds ink. I leave the numbers by which I know this city, its epistemologies and apartheids, its mornings, its slips of paper, its slivers and its seeds, its dry floors and short showers, its roosters that cannot distinguish between the blue of morning and the blue of night.

I leave the coffee spilled onto the floor of the bus, your hand between my legs I leave, I leavethis will surely leave a stain. Before Diagnosis The lake is dead for a second time this January. And no matter how many geese lay their warm breasts against the ice or fly across its hard chest, it doesnt break, or sink, or open up and swallow them. The ice is frozen water. There is no metaphor for exile. Even if these trees continue to shake the crows from their branches, my sister is still farther away from her mind than we are from each other, sitting on opposite ends of a park bench waiting for evening to swallow us whole.

In the last moments of a depressive, a sun. In the last moments of a sun, my sister says a man is chasing a goose through the snow. Cross Country When I ran, it rained niggers. Early in October the first creases of autumn, a flag-weary sky in which yellow birds, in flight, slip through the breast bone of God and tear at the coarse threads that keep the morning knit tightly around his heart. What was it that they sang about the light, their tongues, the thistles they pluck from the bitter bark of an allthorn then thrust into the breast of whatever god or good animal requires eating, a good piercing? These blond bodies thrashing about above me were deaths idea of the morning passing. Here, below this golden altar, the making and unmaking of my body.

The kettle-clank and souring sumac of a man yelling at the light slipping in and out of my mouth. What name must I carry above the dustof this field? Bruised ear, blank body, purple tongue, bloodyGod bleeding do you hear me? Deer piss and poison ivymade pungent by the dew and morning sun rising, do you hear me? When I ran, it rained niggers. In a ditch along the road, a pair of wild boars, slain and laid tusk to tail, point, as if required, in two directions at once, toward my body pressing the last bits of a hunters moon into the tar of this road and away from the meadow-red light coming up through the chaff rising above this hectored field and the man yelling. Nigger in the cicadas tuning up to tear the morning into tatters. Nigger in the squawk and clatter of a hen complaining of a hand reaching below her bottom and removing the warm work of a cold night. Nigger in the reeds covering the muck of a beavers hard birth.

Nigger in the blue hour of a field once wet with the breath of a lone horse cracking along its flanks. Nigger in the fog lifting from this field and the stillbirth it reveals. Nigger in the running. In the bog at the end of this road. In the war and in between the wars. Nigger in the pink salt and eyelashes of a woman I love.

Her mouth pulling water from behind my knee. Pulling, pulling, pulling. Think: nigger is the god of our brief salvation. Nigger in a body falling toward a horizon. Nigger in the twilight that is no longer a twilight but a black creek fumbling along the spine of a boy who is running through a city that is running out of water. Even the lions have left for the mountains.

This is America speaking in translation, in glitter, in gold grills and fried chicken. Auto-tune this if you must. Cher will be singing in the brush of static from the attic radio, believing in love after love or life after love despite the impure thoughts of evening, despite the rain soaking the red head of a red bird now dead in a puddle that refuses to reflect the moon. The Mare of Money for Emmett Till Another dead mare waits in the shoals of some body of water, waits to be burden, borne into a foaming ocean, where it might become food for whales, or simply empty signifierhair latched to the seas undulation like Absaloms beauty caught in the branches of a tree desiring union, entanglement, thick confusion but not this mare; she does not get the luxury of a lyrica song that makes our own undoing or killing sweet even as we go down into the fire to rise as smoke. This horse lies, eyes open, among the stones and freshwater crawfish in Money, Mississippi. On Visiting the Site of a Slave Massacre in OpelousasGrief, according to Dr. On Visiting the Site of a Slave Massacre in OpelousasGrief, according to Dr.

Johnson, is a species of idleness. Then let me be idleidle as one thousand orphaned oars, vessel-less and beached in this cornfield, idle as a field of black women underneath the hoof and boot of a swarm of stallions robed in wedding gownsnot a bride among them. I will mourn for what fails herethe deer, there, dead in the ravinethe bees latching combs of honey to its larynx, lungs, and breast. This is the idol of idle the bees harvesting honey in the good and rotting meat, the drones body, still in the last pitches of pleasure, taken from the queens chamber and cast from the hive by the workers the deer unaware of the work being done in its still body. Sometimes, we entertain angels and violent strangers unawares. You should know