Swallow Press / Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701

www.ohioswallow.com

2009 by John Thorndike

All rights reserved

To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or

distribute material from Swallow Press / Ohio University Press

publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at

(740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax).

Printed in the United States of America

Swallow Press / Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper

16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

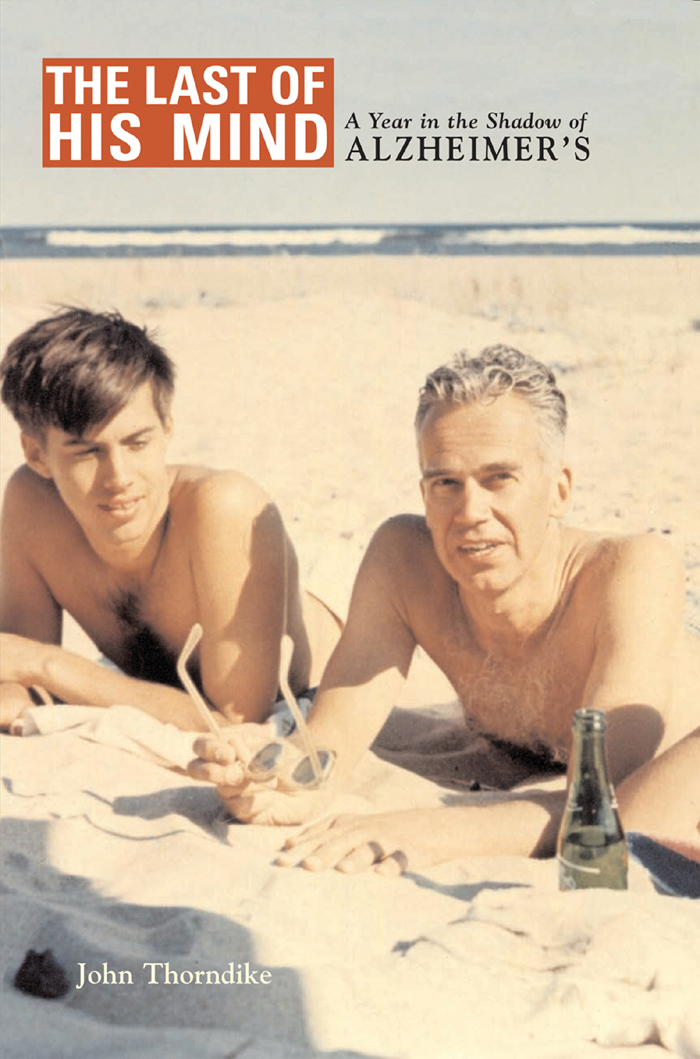

Thorndike, John.

The last of his mind : a year in the shadow of Alzheimers / John Thorndike.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-8040-1122-8 (hc : alk. paper)

1. Thorndike, Joseph Jacobs, 1913 Mental health. 2. Alzheimers diseasePatientsUnited StatesBiography. 3. EditorsUnited StatesBiography. 4. Authors, AmericanUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

RC523.T575 2009

362.1968310092dc22

[B]

2009026118

For the radiant

Maximo Holst Thorndike

It was all leaving her in slow, imperceptible movements, like the tide when ones back is turned: everyone, everything she had known. So all of grief and happiness, far from being buried with one, vanished beforehand except for scattered pieces. She lived among forgotten episodes, unknown faces bereft of names, closed off from the very world she had created; that was how it came to be. But I must show nothing of that, she thought. Her childrenshe must not reveal it to them.

James Salter

Contents

The Last of His Mind

Acknowledgments

Thanks to my readers: Lois Gilbert, Sandy Weymouth, Janir Thorndike, Alan Thorndike, Ellen Thorndike, Bob Ginna, Natalie Goldberg, Eddie Lewis, Henry Shukman, Biddle and Idoline Duke, Paul Kafka-Gibbons, Ted Conover, Kathy Galt and Beth Kaufman.

Thanks to Harriet Guyon, Jack Lane and Marion Prendergast for the spirited and tender care they gave my father.

Thanks to the clear-sighted staff at Swallow Press. As a writer, Ive never been treated better.

Thanks to the Ohio Arts Council for a 2007 Individual Excellence Award.

And thanks to three havens where writing came easier: The MacDowell Colony, The Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and the Brooks Free Library of Harwich, Mass.

December

My father sleeps through the December afternoon. He has always resisted a nap, doesnt believe in them, yet now lies on top of his bed wearing a winter coat and his red fleece hat, snoring lightly. Hes ninety-one. For an hour he doesnt move, his head tilted back against the pillow and his hands interlaced on his chest. Another hour and the light begins to fade outside. Finally I walk down the hall and tap on the doorjamb. I stand beside the bed, listening to his shallow breaths and watching his old face: his half-open mouth, the crust in the corners of his eyes, his patchy skin and tumultuous eyebrows.

Dad? Do you want to wake up?

He opens his good eye but doesnt say anything, just stares without moving. Outside, the long Vermont dusk is settling. Every Christmas Dad stays in this downstairs bedroom in my brothers housebut now his eye shifts from chair to window to door and back, making me wonder if he knows where he is. After a couple of minutes he hunches himself up against the headboard. I try not to hurry him, because Im always groggy myself after a long nap.

Resting in bed, he wears the old pair of slippers Al has given him, wide and brown and flattened at the heels. His feet are too swollen to fit into his shoes, and theres no chance this year that he will tramp across the meadow with the rest of us through six inches of new powder, as he did last Christmas.

When I turn on the table lamp with its cheerful yellow glow, he sits up and lowers his feet to the floor.

What time is it?

Four-thirty, I say, reading off the digital clock on the table beside him.

Is it night?

Almost.

His face is still lopsided from sleep, but both eyes are open. He takes off his hat and flexes his bony hands on the edge of the bed. I stand beside him until my brother walks in with some papers. Al has drawn up a couple of documents that will allow him to take over more of Dads finances. Someone has to do this, because he can no longer keep up with them on his own. He wants to balance his own checkbook, but Ive watched him try and he cant do it. He keeps records but theyre scattered, and hell sit at his dining room table for thirty or forty minutes trying to figure out whats wrong. Dates, names, money, mathits all slipping away from him.

Al takes his time. He asks Dad if hes warm enough, if hed like a glass of water, and gives him some time to finish waking up. But when he holds out one of the documents and explains how this will make things easier for all of us, Dad balks.

Ive given up too much already. I dont want to sign anything.

All this one does, Al says, is add my name to your bank account so I can make sure the bills get paid. Its still your money. There wont be any change for you at all.

Therell be a big change. I wont be the one in charge anymore.

He doesnt look at us, but he knows whats going on. His mouth turns down as if we have already deceived him.

Dad, I tell him, youll always be in charge. All you have to do is talk to Al and hell do whatever you like.

Weve never backed our father into a corner like this. Weve asked him to stop driving and to accept help with his medications, but hes never had to sign anything. Al stands in front of him with pen and paper, but Dad shakes his head. He stares down at the floor, at the carpet, at his feet in their slippers. I dont want to.

In the boxy silence that follows his refusal, I become aware of my patience, as if its a commodity Im spending. I dont know how much I have.

Al tries to explain. If checks bounce, he tells Dad, or if bills dont get paid, its a problem for everyone. I noticed this fall that some of your bills were overdue. It would really make things easier for us if youd let me pay them.

Dad looks away. For a long time he doesnt say anything, and when he finally glances at us I think hes going to give in. Instead he says, I want to go home.

He stares again at his feet. The windows are now black with night.

I want to go home and take care of my own money and be in my own house.

Well be going back, I assure him. Im going to drive you back after Christmas.

I want to go now.

How desolate this sounds. I am tied to him. I have brought him here and must take him back, and now have a bleak vision of the two of us sitting in his house on Christmas Eve on snowless Cape Cod, far from my brother and the rest of the family. We would eat some small dinner, sit in his living room and exchange a present. We would read. It makes me lonely just to think about it. Dads two favorite times of year are the family reunion in August and Christmas at Als in Vermontyet now he wants to go home.

I want to keep my house, he says.

Your house is yours, Dad. Were not taking that away.

But he will not sign anything, not tonight. Al puts the papers back in a folder, and we reassure Dad that both house and money are his, and he can make all decisions about them. Slowly, by talking about our holiday plans, we bring him around. Als two boys, Porter and Ted, will be here, some friends and neighbors will stop by, and well telephone our other brother, Joe Jr., and my son, Janir, whos spending Christmas with his wifes family. Dad stops talking about going home, but its another hour before the stark look leaves his face, of someone hunted and trapped.