TO MIREILLE

At the center of our moral life and our moral imagination are the great models of resistance: the great stories of those who have said No.

SUSAN SONTAG

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

About a mile beyond the main square in the village of Jzefw, in eastern Poland, several dozen wooden stakes poke out among the weeds and bushes on a patch of forest strewn with pinecones and covered in velvety green moss. The stakes are nestled in a thicket of pines on the outskirts of the village, across the road from a murky pond. They would be easy to miss, rising a mere foot or two above the ground, but surrounding them is a waist-high band of blue-and-white ribbons festooned around the trunks of some of the neighboring pines. On the still summer day I followed a footpath through the trees to the edge of this ringed enclosure, the forest was eerily quiet, as though in deference to the villagers whose names were listed on the small, mud-stained notices pinned to the wooden stakes. Sheathed in plastic, the notices were inscribed with hexagonal Jewish stars, Hebrew lettering, and a date13/7/42.

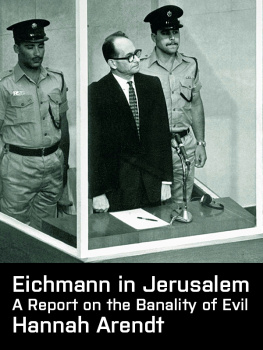

Early that morning in 1942, before daylight broke, Jzefw was equally still. Then a convoy of trucks rattled by. They came from Bilgoraj, roughly eighteen miles to the west, carrying the men of Reserve Battalion 101, a division of the German Order Police whose members announced their presence by rousing the villages eighteen hundred Jewish inhabitants from their homes. The villagers were taken to a marketplace, where the male Jews of working age were separated outthey were destined for a labor camp. Most of the otherswomen, children, elderly peoplewere driven in trucks to the edge of a path leading into the woods, marched inside in small groups, and forced to lie face down in rows. The soldiers lined up behind them, placed the tips of their carbines at the base of their targets necks, and, against the wail of screams that soon echoed through the forest, fired. The first shots rang out in the morning and continued into the night, a marathon of murder that left the woods littered with corpses and body parts. In the shade of the pines, skullcaps were torn off heads. Soldiers emerged from the wilderness splattered in blood, pausing for an occasional smoke before circling back with a fresh batch of victims.

In the knapsack that I carried on my own trek into the forest was a copy of the book Ordinary Men , by the historian Christopher Browning, a study of the battalion that swept through Jzefw that includes a chilling account of the massacre. Id read the book long before visiting the scene of the crime but the details had stayed with me, both because of something startling it revealed and because of something I remember feeling it had left out, something I wanted to know more about. The startling revelation concerned not the shootings but a moment that preceded them, when the commander of the battalion, Major Wilhelm Trapp, gathered his men in a semicircle to deliver an address. As one might expect, Trapp reminded the soldiers, only a quarter of whom were members of the Nazi Party, that Jews were the enemies of Germany. Then he announced that if any of the older men did not feel up to participating in the operation, they could refrain. There was a pause, and a soldier stepped forward. About a dozen more followed.

It is an arresting moment, a brief but pregnant exchange that upends the notion that the rank-and-file soldiers who took part in the massacre had no alternative but to participate. They did not join the firing squads because they had to. They joined because they chose to, which raises the question of what ultimately drove them to kill. Browning traces the answer to the fear of standing apart from the group: not taking part in the operation meant leaving the dirty work to ones comrades and being seen as casting negative judgment on ones nation and peers, something most of the soldiers in the battalion were loath to do, particularly for the sake of people who were, after all, Jews.

But there is another, equally compelling question that has gone comparatively ignored: namely, why a few ordinary men considered Major Trapps offer and turned in their guns. Why, even in situations of seemingly total conformity, there are always some people who refuse to go along.

* * *

This is a book about such nonconformists, about the mystery of what impels people to do something risky and transgressive when thrust into a morally compromising situation: stop, say no, resist. The extreme circumstances that prevailed among the German soldiers tasked with hunting down and murdering Jews in villages such as Jzefw during World War II are, fortunately, something most of us can only imagine being caught up in. Yet there is a reason our imaginations are often drawn to such scenarioswhy few of us have failed to wonder at some point whether the impulse to refuse would have gripped us if wed stood in the shoes of ordinary Germans back then, and, if so, whether we would have had the nerve to act on it. Wondering this is not, in fact, a purely speculative exercise, owing to an unresolved tension that runs through most societies, and for that matter most peoples minds. Weve all arrived at junctures where our deepest principles collide with the loyalties we harbor and the duties we are expected to fulfill, and wrestled with how far to go to keep our consciences clean. As far as necessary to be true to ourselves, a voice inside our heads tells us. But there are other voices that warn against turning on our community, embarrassing our superiors, or endangering our careers and reputations, maybe even our lives and the lives of our family members.

In Hollywood films and the sanctimonious tributes that have grown increasingly common in recent decades, individuals who stand by their convictions at such moments are invariably depicted as heroes. Trees are planted for them at places like the Yad Vashem Memorial Museum in Jerusalem. Politicians salute them for reminding us of our moral duty to confront evil in all its forms, as George W. Bush stated upon awarding the U.S. Medal of Freedom in 2005 to Paul Rusesabagina, the hotel manager who risked his life to shelter Tutsis during the 1994 Rwandan genocide (and whose story served as the basis of the movie starring Don Cheadle, Hotel Rwanda ). After a century of horrors fueled by obedience and conformity, who could argue with this? Surely one of the lessons the civilized world learned from the cataclysms of the modern era is that averting ones eyes from blatant wrongdoing is untenable. Yet confronting evil tends to be seen differently when it is being committed in our namewhen the perpetrators are not Germans or Rwandans but Americans carrying out abuses at places such as the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, a story that came to light after a reservist named Joseph Darby handed a CD full of incriminating photos to the U.S. Armys Criminal Investigation Division in 2004, one year before President Bush honored Paul Rusesabagina. Darbys reward was to be called a traitor and to receive a string of death threats that prompted him to move out of his hometown.

The speed with which people like Darby are ostracized even in democratic societies shows how much easier it is to admire such nonconformists from a distance than up close, when the beliefs being challenged are ones own. It also illustrates how acts of conscience that some view as heroic may strike others as acts of betrayal, subversion, or irresponsibility. This is the fear that stalks the narrator of Khirbet Khizeh , a novella published in 1949 that tells the story of an Israeli army unit dispatched on a mission to clear infiltrators out of a village during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Written by S. Yizhar, the pen name of Yizhar Smilansky, a veteran of that conflict, the novella records the inner torment of a soldier who comes to realize the targets of the operation are unarmed civilians. Ordered to load the villages inhabitants onto trucks and demolish their homes, the soldier balks. If someone had to get filthy, let others soil their hands, he tells himself. I couldnt. Absolutely not. But immediately another voice started up inside me singing this song: Bleeding heart, bleeding heart, bleeding heart. With increasing petulance and a psalm to the beautiful soul that left the dirty work to others, sanctimoniously shutting its eyes, averting them so as to save itself from anything that might upset it, with eyes too pure to behold evil. Overcoming his queasiness, the soldier ends up submitting to the order, and is then haunted by the thought that hes colluded in a crime.