Radical Treatment

Radical Treatment

Wilder Penfields Life in Neuroscience

RICHARD LEBLANC

McGill-Queens University Press

Montreal & Kingston London Chicago

McGill-Queens University Press 2020

ISBN 978-0-7735-5928-8 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-2280-0019-8 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-0-2280-0020-4 (ePUB)

Legal deposit first quarter 2020

Bibliothque nationale du Qubec

Printed in Canada on acid-free paper

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Montreal Neurological Institute.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.

Nous remercions le Conseil des arts du Canada de son soutien.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Radical treatment : Wilder Penfields life in neuroscience / Richard Leblanc.

Other titles: Wilder Penfields life in neuroscience

Names: Leblanc, Richard (Neurosurgeon), author.

Description: Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190191015 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190191058 | ISBN 9780773559288 (cloth) | ISBN 9780228000198 (ePDF) | ISBN 9780228000204 (ePUB)

Subjects: LCSH: Penfield, Wilder, 18911976. | LCSH: NeuroscientistsCanadaBiography. | LCSH: NeurosurgeonsCanadaBiography. | LCSH: Neurosciences. | LCSH: Nervous systemSurgery. | LCSH: NeurosciencesPhilosophy. | LCGFT: Biographies.

Classification: LCC R464.P46 L43 2019 | DDC 610.92dc23

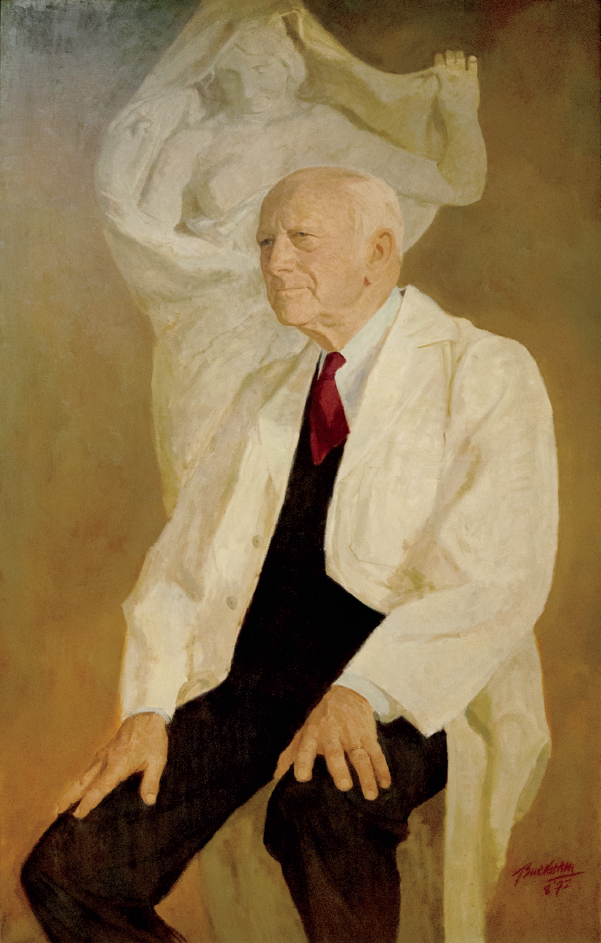

Frontispiece: Portrait of Wilder Penfield in front of Nature Unveiling Herself before Science. Lynn Buckham. Montreal Neurological Institute and McGill University.

Drawing is the honesty of art Dal

Contents

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to all who have supported the Thomas Willis and the Neuro History Funds of the Montreal Neurological Institute. This book would not have been published without their generosity. I also owe a great debt of gratitude to Helmut Bernhard who photographed the brain maps that illustrate this book and to Ann Watson for so many things. This book is dedicated to Kathleen and Katherine, who will always be in the front row with me.

Radical Treatment

Figure Intro.1. Penfield is seen giving advice to William Feindel from the gallery of the Montreal Neurological Institutes Theatre One. Feindel later became the third director of the Montreal Neurological Institute, succeeding Theodore Rasmussen. Montreal Neurological Institute and McGill University.

Introduction

This book addresses Penfields thinking as it evolved from his description of brain scars at the beginning of his career, to his last thoughts on the human condition. It is based on a review of Penfields clinical charts, my reading of his writings over the course of my career as a neurosurgeon and physician-scientist at the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI), and my encounters with his pupils, who were also my teachers in the care of epileptic patients.

Penfields clinical charts are the foundations that support his scientific edifice. Each chart contains a patients history, physical examination, and radiological findings. The charts of patients admitted to the MNI after 1938 also contain Herbert Jaspers EEG reports and the minutes of the Clinical EEG Conference, where every patients case was discussed before a decision was made to operate. The heart of each patients chart is Penfields detailed operative report and the meticulously detailed recording of the effects of electrocortical stimulation. Penfield or his assistant initially wrote these down on the side or on the back of each patients brain map, and, after the MNI opened its doors, they were dictated to a secretary in the gallery of the operating room. Each map illustrates Penfields operative findings and the cortical and subcortical pathology that he encountered at craniotomy. They localize the points where electrical stimulation of the cortex produced somatosensory, visual, verbal, or motor responses. The brain maps also illustrate the sites from which epileptic activity was recorded and from which epileptic seizures were generated by cortical stimulation. Intraoperative photographs were also taken to complement the sketches, but the sketches were Penfields principal tools. The photographs are accurate but they have limitations. The exposed brain is a half-sphere and the early cameras had limited depth of field. The brain pulsates when it is exposed, and the early photographs are sometimes blurred. The camera captures every detail without discernment, but it cant capture what is not exposed to the lens the medial aspect of the frontal lobe where the supplementary motor area resides, the undersurface of the temporal lobe, the hippocampus at the depth of the surgical exposure, the insula in shadow, the subcortical infiltration of a brain tumour. All of these were recorded in the sketches.

Sketches eliminate the superfluous. They are selective in what they highlight a constricted artery, a reddish draining vein, the feel of a sclerosed hippocampus. Photographs dont speak to us the way that sketches do: the sketches were annotated as insight arose from observation, and the notes found their way into Penfields lectures and texts.

Readers will be surprised at Penfields informal training in neurosurgery. Although he met Harvey Cushing early in his career, he was one of the few North American neurosurgeons of his generation who did not train with him. Penfields formal training in neurosurgery, such as it was, was with Percy Sargent, the senior neurosurgeon at the National Hospital for the Paralyzed and Epileptic at Queen Square, London. Penfield assisted Sargent in the operating room and cared for his postoperative patients on the wards. His first published paper on a neurosurgical topic was a review of Sargents cases of osseous brain tumours. But Sargent taught Penfield more than how to turn a bone flap or remove a brain tumour. Penfield would also have observed Sargent resect cortical scars from epileptic patients, and from Sargent he would have learned of the vascular hypothesis of epileptogenesis, to which he devoted the first decade of his career. This is an aspect of Sargents influence on Penfield that has not previously been addressed. It was however Otfrid Foerster, a German neurosurgeon of international repute, who had the most profound influence on Penfield, as he adopted Foersters method of investigating and treating posttraumatic epilepsy. Penfields career took flight after his stay with Foerster.

Penfields first academic interest in Montreal was the investigation of the vascular hypothesis of epileptogenesis. This held that posttraumatic seizures arise as a result of transient ischemia of the cortex surrounding a cortical scar. Penfield was the first to describe the components of cortical scars, their gradual contraction, and the resultant pull on cortical arteries that he thought triggered reflex vasoconstriction and posttraumatic seizures. This led Penfield to discover intracranial vasoactive nerves, which supported the vascular hypothesis, and to study cortical blood flow, which disproved it.

Next page