Your Guide to Mesa Verde National Park, First Edition (electronic)

ISBN: 978-1-62128-027-9

Published by: Stone Road Press

Author/Cartographer/Photographer/Designer: Michael Joseph Oswald

Editor: Derek Pankratz

Copyright 2012 Stone Road Press, LLC, Whitelaw, Wisconsin. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise without written permission of the Publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Stone Road Press; c/o Michael Oswald; 4927 Stone Road; Whitelaw, WI 54247.

The entire work, Your Guide to the National Parks is available in paperback and electronic versions. Content that appears in print may not be available electronically.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-62128-000-2

Library of Congress Control Number (LCCN): 2012934277

Printed in the United States of America

E-Book ISBN: 978-1-62128-0 65-1

Corrections/Contact

This guide book has been researched and written with the greatest attention to detail in order to provide you with the most accurate and pertinent information. Unfortunately, travel informationespecially pricingis subject to change and inadvertent errors and omissions do occur. Should you encounter a change, error, or omission while using this guide book, wed like to hear about it. (If you found a wonderful place, trail, or activity not mentioned, wed love to hear about that too.) Please contact us by sending an e-mail to . Your contributions will help make future editions better than the last.

You can contact us online at www.StoneRoadPress.com or follow us on

Facebook: www.facebook.com/thestoneroadpress

Twitter: www.twitter.com/stoneroadpress (@stoneroadpress)

Flickr: www.flickr.com/photos/stoneroadpress

FAQs

The world of electronic media is not cut and dry like print. Devices handle files differently. Users have a variety of expectations. These e-books are image- and map-intensive, requiring fairly powerful hardware. All books were tested for use on the Kindle Fire, Nook Tablet, and iPad. You can expect to have the best user experience on one of these devices, or a similar tablet, laptop, or desktop. In the event you have issues please peruse our Frequently Asked Questions (.

Maps

Numerous map layouts were explored while developing this e-book, but in the end it was decided that the most useful map is a complete one. Unfortunately, due to file size concerns and e-reader hardware limitations, some maps included in this guide book are below our usual high standards of quality (even using zoom features). As a workaround all of this books maps are available in pdf format by clicking the link below each map or visiting www.stoneroadpress.com/national-parks/maps .

Disclaimer

Your safety is important to us. If any activity is beyond your ability or threatened by forces outside your control, do not attempt it. The maps in this book, although accurate and to scale, are not intended for hiking. Serious hikers should purchase a detailed, waterproof, topographical map. It is also suggested that you write or call in advance to confirm information when it matters most.

The primary purpose of this guide book is to enhance our readers national park experiences, but the author, editor, and publisher cannot be held responsible for any experiences while traveling.

Mesa Verde - Introduction

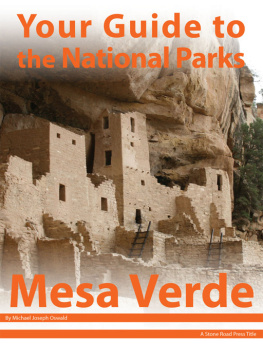

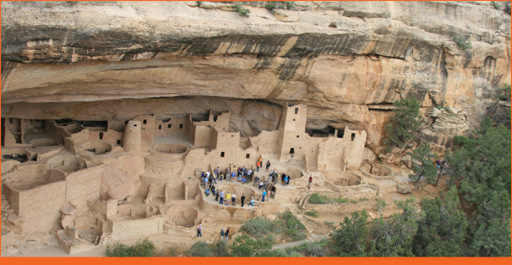

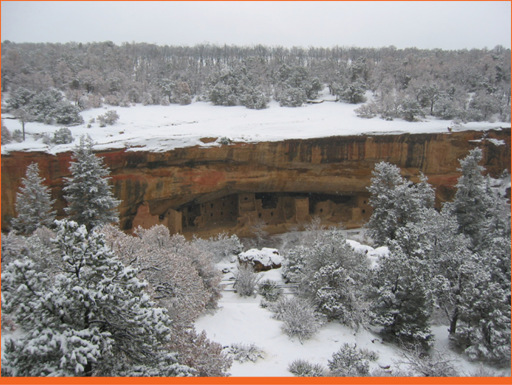

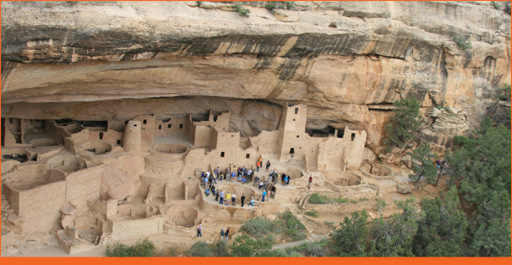

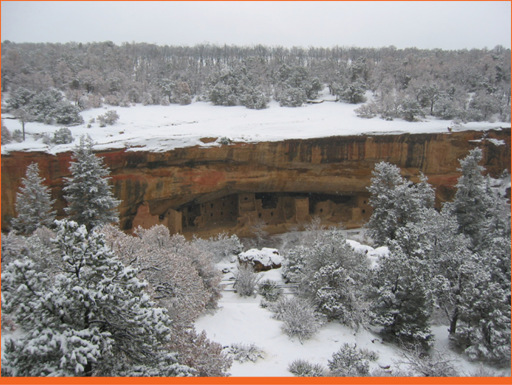

Cliff Palace: more than 150 rooms, 21 kivas, and home to approximately 100 ancestral Puebloans during the 13th century

Lets say you arrive at Mesa Verde completely unaware of the areas history and culture. A quick drive across the mesa and you would be left scratching your head, wondering where the majestic scenery went. Mesa Verdes deep gorges and tall mesas have a bit of scenic appeal, but it pales in comparison to other southwestern parks. But what it lacks in natural beauty it redeems in cultural significance. When the park was established in 1906, it became the first tract of land set aside to protect a prehistoric culture and its ruins, pottery, tools, and other ancient artifacts .

Somewhere around 750 AD, Puebloans were living in modest pit-houses on top of the mesa, clustered together forming small villages. They found sustenance farming and hunting. Judging by the circular underground chambers, called kivas, religion was important and rituals and ceremonies were performed regularly. By the late 12th century they began building homes in alcoves beneath the rim of the mesa. These cliff dwellings became larger and more numerous.

Scientists and volunteers are attempting to piece together the history of Ancestral Puebloan People by scouring thousands of archeological sites. To date, there are more than 4,700 archeological sites within the park; roughly 600 are cliff dwellings . About 90 percent of the cliff dwellings contain 10 rooms or less, but a few are enormous. Cliff Palace , the largest and most famous dwelling, contains 150 rooms. Long House and Spruce Tree House exceed 100 rooms, and Balcony House has more than 40. These sites have attracted archeologists and vandals, pothunters and politicians, tourists and explorers.

John Moss , a local prospector, is the first person in recorded history to have seen the ruins. In 1874, he led a photographer through Mancos Canyon along the base of Mesa Verde. Resulting photos inspired geologists to visit the site in 1875, and more than a decade later Richard Wetherill and his brothers began the first serious excavations. They spent the next 15 months exploring over 100 dwellings. Frederick H. Chapin , a noted mountaineer, photographer, and author, aided the excavation. Later, he wrote an article and book on the areas geologic and cultural significance. In 1889 and once again in 1890, Benjamin Wetherill wrote to the Smithsonian, warning that the area would be plundered by looters and tourists if it was not protected as a national park. He also requested that he and his brothers be placed in the employ of the government to carry out careful excavation of the ruins even though they were not legitimate archeologists.

The requests went unanswered, and the following year the Wetherills hosted Gustaf Nordenskild of the Academy of Sciences in Sweden. Using scientific methods and meticulous data collection, he began a thorough excavation of many ruins including Cliff Palace. Incensed locals charged Nordenskild with devastating the ruins and held him on $1,000 bond when he tried to transport some 600 artifacts, including a mummified corpse, on the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad. He was released because no laws existed to prevent treasure hunting. The artifacts were shipped to Sweden and today they reside in the National Museum in Helsinki, Finland. Upon his return home, he examined the artifacts and published a book titled The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde .

At this time, Pothunters and vandals were becoming a serious problem. Dynamite was used to blow holes in walls to let light in or to scare away rattlesnakes. Colorado Cliff Dwelling Association (CCDA) picked up the mantle of advocating a national park. But when Virginia Donaghe McClurg, head of the CCDA, expressed her opinion that it should be a womans park, Lucy Peabody left the association and continued to search for support on her own. Finally, in 1906 President Theodore Roosevelt signed a bill creating Mesa Verde National Park, protecting an area of unique history and culture for future generations.

Cliff Dwellings (MEVE)

Next page