I n the afternoon, I drove up the D 675 to Cresseveuille. At that moment my thoughts couldnt have been further aw ay from Gonzague Saint Bris. An eccentric journalist, right-wing admirer of Louis XI, he had crossed the alps on the back of a mule in order to emulate Leonardo da Vinci, having previously founded the very swanky Academie Romantique, a cultural group of high-profile French intellectuals.

That 8 August, in 2017, at the age of 69, the fashionable writer died in the old-fashioned way: the car wrapped around a tree on the D 675, which links Rouen to Caen, the romanticism of Cabourg to the horse tracks of Deauville.

I am a woman of the coast, of pearl greys and blurred blues: they illuminate the sea of Normandy. I distrust the dense hinterland, with its leafy calm, its ponds that threaten to drown you, its thatch at the mercy of rot. And yet, I have ventured inland. I have come to visit Cresseveuille. Like a return to the scene of the crime. It was here that Jane and Serge spent holidays with their daughters.

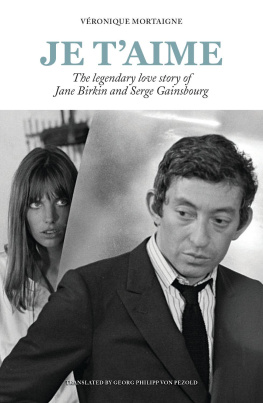

In December 1971, the young Gonzague Saint Bris is 23 years old. He publishes one of his first articles in Le Figaro, entitled Gainsbourg has reached his cherry season. The middle of lifes journey. Gainsbourg, then 43, is as ripe as a Morello cherry in the sun. He sings: a derisive cockerel. Gainsbourg, Saint Bris writes, is the epitome of a commercial artist: he sprinkles his lyrics with brand names, with Guerlain perfume and advertisements for aperitifs. Gainsbourg is not handsome, to say the least. But he has done what should be done in such a case: elevate ugliness to an art form. A difficult undertaking that he has mastered as he will master many others: with ease.

Gonzague Saint Bris errs in one respect. Nothing had been easy. The whole endeavour might have capsized if Gainsbourg hadnt met Jane Birkin in May 1968. The leafy green of Normandy was the backdrop to his metamorphosis. This is where he became beautiful. The transformation took time. It took several seasons to develop.

Gainsbourg has spent lots of time in Normandy with his family. During the pre-war years, they roamed the beaches in the summer. Joseph, his father, made a living playing the piano in casino bars. In 1975, Jane, his young English lover and the mother of his daughter Charlotte, buys a house in Cresseveuille, at a stretch of the D 675, the fatal route where Gonzague Saint Bris partner tried to avoid an animal before going off the road. In this Normandy, descended from Viking heathens, some might detect the hand of the Dames Blanches the local female spirits and other creatures of a parallel world, which has been transformed by Christian fervour over the centuries into a cauldron of punishment and devilments.

It was Rgine, the Queen of the Night, who, in 1968, played good fairy to that happiness born in Normandy. With her, Serge enjoys memorable fits of laughter. Rgine had bought a house near Honfleur the photographer Tony Frank, who was there (throughout the mythical couples love story) relates. Serge, Jane and her daughter Kate in the grass, entwined bodies and conspiring glances: Tony Frank is a player. He sees everything, accompanies them everywhere. They are beautiful. They occasionally spend the day at the seaside, a big crowd gathered around Janes entertaining brother Andrew. They were in love like infatuated youngsters, they played about like kittens. This inspires legendary photos, and bags of memories. Rgine takes out a used bottle of Martini wrapped in newspaper. It was moonshine calvados from the local bootlegger. Chess is being played, the bottle gets emptied, then another. I took them to a station I dont remember which one. Tony Frank, formerly a fellow-traveller of the Hallyday tribe, still sports even today the iodised tan of celebrity photographers.

Jane uses the money she made in 1974 from Claude Zizis film Im Losing My Temper to buy an impossibly pretty little vicarage, perched next to the church, nothing Norman about it; a slate roof, Ive added a storey and a toilet. The escapades with friends and family end in Deauville, Chez Miocque: a restaurant displaying signed celebrity photos on the walls, offering fish of the day and apple tart, or at the bar of the Normandy, invariably cosy, with its collection of rare whiskies and sporting pictures.

A picture, signed Siss, hangs prominently in the left hand corner above the best table for observing the comings and goings of celebrities. It depicts the Gainsbarre of depression: an empty gaze, he is alone with his bitch Nana. Stubble, white ballet shoes and jeans. Cigarette butts litter the floor; he plays the organ grinder, makes a performing dog dance with no spectators other than a couple of pigeons. It took some melancholy to shatter that joy! In ten years, everything has broken down. Cresseveuille was where the seeds that would destroy that happiness were planted. Serge Gainsbourg changed from an insouciant with a twig between his teeth, from a mischievous doting father, to Gainsbarre, drinker of 102: a double measure of Pastis 51.

Jane Birkin loved her vicarage between cemetery and motorway, with rusty crosses and all. It is gone. Gainsbourg has lost. Jane cleared off to the department of Finistre, to Lannilis, where Serges father had supported the French Resistance. All that remains of the house of Norman happiness is a grey wall and a light signal above a great gate that was meant to flash when visitors came and went, but which is now permanently off. It is attached to the Church of Notre Dame de lAssomption, whose foundations were laid in the flinty ground during the 13th century and whose wooden nave is like an upside-down boat, with its adjacent wash house.

Everything about the couples life in the Norman village has already been said. Yes, Serge went shopping on his Solex moped, for drinks at Gerards, in the village of Danestal, or at Annis at Beaufour-Druval. Yes, we have glimpsed one of the Magnificent Seven, the actor Yul Brynner: a handsome and mysterious Russian Jew with a shaved head. Surrogate godfather to Charlotte, he came for neighbourly visits from his mansion at Bonnebosq, some fifteen kilometres away. An octogenarian farmer confides that he often drank with the singer, while another neighbour claims that his drinking bouts didnt last too long, adding that he was a good family man. He laughed with the children and worked at night.

When Serge and Jane return to Paris, they entrust the house to a local farmer they befriended, Ren Touffet, aka Toto. We are not going to get to the bottom of the enigma in this way.

The magic of Jane and Serge, a unique presence, a couple united by happenstance and need, reveals itself only in details. Its the parts that make the whole. For such sensitive, thin-skinned individuals, leaving for a small Norman village couldnt have been without meaning.

The D 675 is dangerous, as everybody knows. It used to be a trunk road, shoving itself into the Pays dAuge, where the greenery hides more than just apple trees, cows and calvados. Closer to the sea, everything, or almost everything, ends in ville: Trouville, Deauville, Benerville, Tourgville, Blonville. However, in the woodland retreat where the couple had decided to spend their summers, its a different kettle of fish. All along the D 675 sleepy towns with strange names are nestling: le Petit-malheur, la Haie-tondue, la Queue-deve, la Forge, le Calvaire