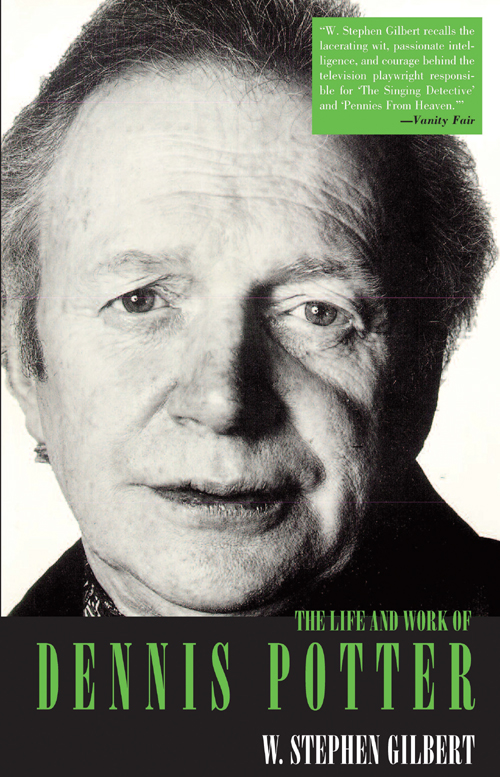

First published in the United States in 1998 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

Copyright W. Stephen Gilbert 1995

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-46830-561-6

For my father Stanley and in memory of my mother Enid and for my mother in the business, Betty Willingale

To pin a man down in a few hundred pages takes a certain callousness as well as a modicum of love a little in the same way that a boy will cheerfully hold up a dragonfly, crucified on a postcard with drawing pins, for the admiration and enlightenment, or even sometimes the pity, of his companions.

Dennis Potter

Section one

Section two

Books of this kind depend on generous helpings of other peoples time and trouble, experience and advice, access and organisation. I have interviewed many who knew and worked with Dennis Potter. Rather than gather their names in a list both indigestible and fraught with the dangers of unintended implications of precedence, I would rather suggest that these individuals quoted contributions within the text be taken as indicative of my gratitude. Some of those who kindly talked to me have not in the end been quoted directly, omissions dictated by the needs of my narrative or the inadequacies of my conduct of it rather than by any judgement of the value of their contributions. I content myself with the belief that, as they are all in the business in one capacity or another, they will perceive the importance of subtext and understand that their input was in no sense wasted.

If I single out four individuals here, those not so favoured will not be dismayed. Dennis Potters mother, Mrs Margaret Potter, and his sister, Mrs June Thomas, made me welcome in their home with great good humour, open-hearted trust (which I hope I have not let down) and encouraging enthusiasm for my project. Miss Iris Hughes, Potters school teacher, was no less kind and informative. And Kenith Trodd, Potters most frequent and enduring collaborator, fielded my every trivial query with patience and gusto, despite being successively in production with Karaoke and in pre-production with Cold Lazarus (his assistant Alexandra Harris was a brilliantly intuitive go-between).

With characteristic self-effacement, John Wyver allowed me to make off with the manuscript of his unpublished book about Potter and with his accumulated research. This is a flying start in anyones language. My own researches made me dependent upon the sympathetic efficiency of several great institutions. Not the least of these was the BBC where Nicholas Moss, Head of Policy and Management, smoothed the path of access; Paul Almond and his assistant Shelley Simmons patiently arranged for me to see recordings, many of which fell well outside their natural purview; and the top-of-the-range staff at the BBC Written Archive Centre at Caversham, led by Jacqueline Kavanagh and (in my case) featuring Jeff Walden, gave me unflaggingly sunny and expert service.

At Channel 4 Chris Griffin-Beale, with unrivalled ebullience, went into immediate action; his assistant Nick Dear kindly did the chores. The ITV companies have become much more difficult (more businesslike?) for a freelance to bend to his will, but I am at least grateful to Richard Cox at LWT for his good-natured account of the ways of the world. (Clare Telford of The South Bank Show sprang to my assistance, however.) It was the British Film Institute which more readily (and economically) screened Potters ITV work for me and I am indebted to Briony Dixon and the BFI staff. Gratitude also to Christopher Robinson of the University of Bristol Theatre Collection.

Much of the assistance I received was of the anonymous kind that researchers are apt to take for granted. But the patience and professionalism routinely offered in the following institutions lightens ones task immeasurably. I would like to thank the staff and officers of the Independent Television Commission Library; the Bodleian Library, Oxford (with a mention for Simon Bailey of the Oxford University Archives); the Oxford Union, the Oxford University Labour Group and the Oxford University Dramatic Society; the British Newspaper Library at Colindale; the British Library at the British Museum; the Westminster Reference Library; the Westminster Music Library; the Senate House Library, University of London; and the New Statesman. I am grateful to the following for their permission to reproduce copyright material (see Notes and Sources for details): BBC Written Archives Centre at Caversham Park, Reading, Financial Times Limited, Guardian Newspapers Limited, Isis Publishing Limited, Mirror Group Newspapers PLC, Newspaper Publishing PLC, Times Newspapers Limited.

For selfless advice, I thank Mark Le Fanu of the Society of Authors. For unknowing inspiration, I salute Garry OConnor, the late Richard Ellmann and my old acquaintance Simon Callow. For personal encouragement, I embrace Tony Coult, Roy Battersby, Richard Krupp, Diane Millward, Eric Davidson, Susan Jeffreys, Lynne Truss, Beth Porter, John Lyttle, Anne Karpf and David Yallop. Without the utter inflexibility or the precisely-apportioned praise of my editor, Roland Philipps, the inspired guidance of my agent, Tony Peake, always supplying what I need, whether caution or stimulus, and the gentle understanding of my partner, David James, through this strange preoccupation with somebody else, this book would certainly not have been written.

In writing this book, I have taken the view, not so very radical, that, even in an era gripped by a daily diet of tabloid sensationalism, the work of a great writer is of sufficient interest by itself to sustain a modest study.

In the preface to the British edition which follows, I tried to make clear my intentions with this book to assess Dennis Potters work within the context of his life and the way in which those intentions were, in part, defined by the stance taken by the executors of Dennis Potters literary estate. Additionally, within the book itself I explore Potters own complex attitude toward (auto)biography in I touch on how in his last works, posthumously broadcast, he explicitly forbade the work of biographers.

Naturally, none of this has prevented some critics from taxing me for writing about Potters work in a professional context rather than about the details of his life for their own sake. Typical is a review by a Vancouver psychologist published on the Internet: We learn little about [Potters] childhood and almost nothing about his own marriage and children. Gilberts ideal reader may be another television writer who would relish the details of fluctuating control over productions, impulsive script changes, and heroic work under pressure.

But the book is much less rarefied than that. Potters work is supremely personal and continually informed by his own circumstances. I have explored those circumstances in so far as they redound on his work and left the strictly personal to other kinds of writers.

But if Potters life is in various ways inaccessible behind the smoke screen he threw up, his work is also not as accessible as it might be. Televisions past is rather less readily available than that of cinema, theatre, literature, or any other art form except perhaps radio. While American readers may feel at a disadvantage for never having had the opportunity to see much of the work discussed, in reality few British readers will have been significantly better off for so many of the works, even if originally caught on television, have since passed out of reach. For this reason, I have summarized each of the television works to a greater extent than I would have considered for a book about a screenwriter, stage playwright, or novelist.

![J K Rowling - Harry Potter [Complete Collection]](/uploads/posts/book/117015/thumbs/j-k-rowling-harry-potter-complete-collection.jpg)