Dedication

To those who remained on the paths, on the hills

FOREWORD

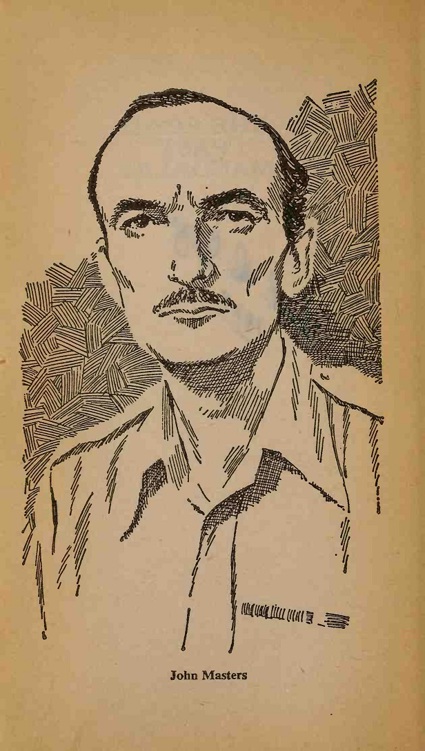

In the foreword to the first volume of my autobiography, Bugles and a Tiger, I wroteThe purpose of this book is to tell the story of how a schoolboy became a professional soldier of the old Indian Army. In the course of the story I hope to have given an idea of what India was like in those last twilit days of the Indian Empire and something more than a tourists view of some of the people who lived there.

The Road Past Mandalay carries the narrative through to the end of the Second World War. Its purpose is to tell the story of how a professional officer of the old Indian Army reached some sort of maturity both as a soldier and a man. Some parts of the story are very unpleasantso was the war it records; others are almost painfully personalbut this is not a battle diary: this is the story of one mans life. Of death and love I cannot say less with honesty or more with propriety.

There is another difference than that of time between this and the earlier volume. I think most people read Bugles and a Tiger for its depiction of a strange and rather romantic kirtd of life led by a very few. This book, The Road Past Mandalay, tells of experiences shared with scores of millions, not yet middle-aged, who have fought in war, have loved, have known separation and discomfort and danger. My story is not unique and I am not a hero, but an ordinary man, and I have written this narrative because I believe that many of you will recognise in it parts of your own life, and know that in writing of myself I have written, also, of you and for you.

As in Bugles I warn that this is a factual story but not a history. I have checked every detail as carefully as I can but as I kept no diary and made no notes my memory may sometimes have deceived me. If it has, again, forgive me.

J. M.

THE ROAD PAST MANDALAY

John Masters

BOOK ONE

ACTION, WEST

Before dawn, the order reached us: The armoured cars of the 13th Lancers were to make a wide outflanking movement into the desert, round the right of the enemys position defending the small Syrian town of Deir-es-Zor. The 10th Gurkhas were to attack astride the main road. Wethe 2nd Battalion of the 4th Gurkhaswere to stay in camp, in reserve, at five minutes notice for action.

My colonel, Willy Weallens, read the message with a darkening face. He jammed on his hat, abruptly ordered me to follow him, and hurried to Brigade Headquarters. When we were admitted to the brigadiers presenceWhy arent we leading the assault, sir? Willy snapped.

The brigadier said that we had been leading for about eight weeks now, and it was someone elses turn. Willy said he didnt see what that had to do with itsir. The order was a deliberate insult to the 4th Gurkhas. Patiently the brigadier explained the benefits of a system of rotation of duties. Willy fumed visibly. He tugged at the brim of his hat, kicked the sand with the toe of his boot, and looked daggers at the brigadier. Although I didnt know it at the time, since I had never seen a baseball game, Willy was giving a perfect demonstration of how to protest a called strike. The result was the same: we remained in reserve.

The brigadier went forward with his command group. Sulkily Willy waited at the main headquarters, at the rear end of the unreeling field telephone line, and I waited with him. Three or four miles ahead Deir-es-Zor gleamed white on its low hill above the right bank of the Euphrates. The dusty road led

straight towards it. To the left a long escarpment of black and grey cliffs marked the southern limit of the arena; the northern limit was the broad, yellow flood of the Euphrates. A neat set-piece battle was about to begin between the Vichy French and their troops, mainly Syrian, who were holding Dier-es-Zor, and the 21st Brigade of the 10th Indian Infantry Division, who intended to capture it. It was early morning on the 4th of July, 1941, and already the temperature had passed 100 in the shade, but there was no shade, except a strong yellow glary kind in the tents. There were only two tents in the whole vast bivouac area. Both were very large and, though a dull brown colour, very conspicuous. One held the Main Dressing Station, full of men wounded in earlier bombing attacks. A large red cross painted on its roof made it more conspicuous still. The other was Brigade Headquarters where Willy and I waited.

An anti-aircraft sentry swung his Bren gun on its mount and peered intently to the west, beyond Dier-es-Zor. Soon I made out nine silver arrows in the sky out there, and diffidently informed Willy that we were about to be bombed again. I added that there were now only two obvious targets in the campthe two tents. The planes were American-built Martin Maryland medium bombers, provided to the French in the early days of the war in order to fight the Germans, and now being used by Petains government against us.

Long dark oblongs formed in the planes bellies as they opened their bomb bays. They came on in a tight formation of three stepped-up Vs, the sun gleaming on their silver bodies. They looked beautiful, and I stepped down into the nearest slit trench. A score of Bren guns began to rattle, and tracer streamed up in long, lovely curves against the blue sky. Directly overhead bombs fell from the bays in a glittering shower. The whistling rose to a multitudinous shriek, the explosions roared, eruptions of earth marched in long parallel lines across the camp. Two bombs fell directly into the Main Dressing Station, killing twenty of the men who lay awaiting evacuation to base hospitals. The Martins wheeled slowly above the sun.

This will be for us, sir, I said. I huddled well down into the trench but watched the bombers, for by now I could judge to within a few yards, just where bombs would land. When the shining bombs left the black bays, I knew that Willy and I were for it. I dived flat in the trench and lay on my face, my arms crossed on the back of my head. Round the angle of the L-shaped trench Willy did the same. Or, I presume he did. He might have thought the pilots up there could see him, and then he would have remained standing, or begun to read a book.

The scream of the bombs grew louder. Suddenly the ground jumped. A huge force lifted and shook me and the trench and the whole earth in which the trench had been dug, moving everything bodily upwards and sideways. Thick yellow earth clogged my mouth and nostrils and I began to choke. A sharp pain on the left cheek of my buttocks forced the earth out of my mouth in a yell.

The thunder of the bombs died away. Through (he cloud of settling earth I heard Willys voice, Are you hit, Jack? I put my hand on my wound, and yelled again. Willy was bending over me with a look of terrible anxiety on his face.

1 thought, what a gentleman you are, colonel dear, and scrambled to my feet. I held out my hand. In the palm lay a still hot .303 bullet, one of ours. Fired at the Martins by a Bren gun, it had become red hot in its passage through the air, and fallen precisely on to my arse as I cowered in the trench, burning a small hole in my trousers and in me. At the same time a 250-pound bomb had fallen about ten feet from my end of the trench. Willy and I were standing in the trench at the rim of the crater it had formed. The force of the explosion had bodily shifted the whole trench, so that it now lay several degrees off its previous line.

The telephone buzzed. The brigadier at the other end ordered us to advance a certain distance behind the 10th Gurkhas, well closed-up and in tight control, ready to repel counter-attacks or to exploit success. A couple of orders and we moved off astride the road. I could hear small arms fire from the direction of