The manuscript of Chindit Affair was re-discovered by the author and journalist Brian Mooney, and he and Antony Edmonds edited it for publication

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Frank Baines, 2011

ISBN 978 1 84884 448 3

ePub ISBN: 9781844683680

PRC ISBN: 9781844683697

The right of Frank Baines to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted

by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording

or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the

Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11 on 13pt Times New Roman by

Acredula

Printed and bound in England

By CPI

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

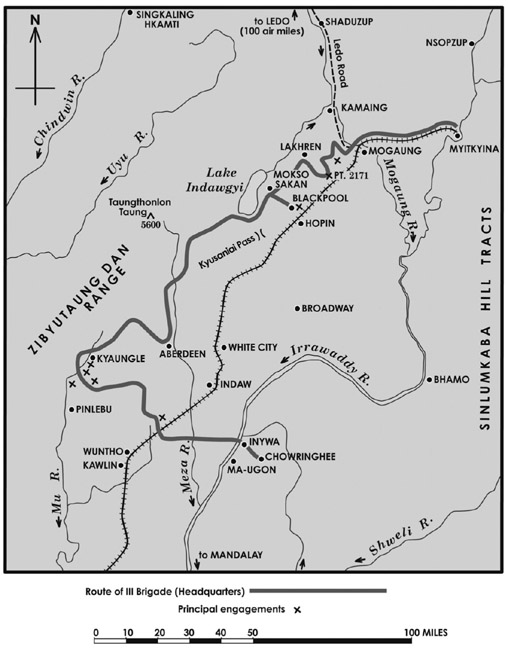

Maps

Burma, 1944

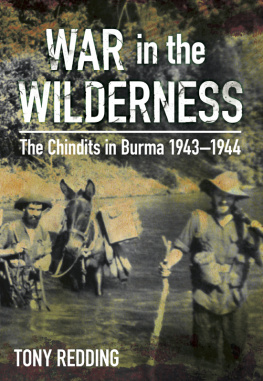

The area in Northern Burma where the Chindits 111 Brigade operated behind enemy lines from March to July 1944.

Operations of III Brigade, Burma, 1944

The route 111 Brigade marched through enemy-occupied Burma, and the main points of engagement with the Japanese. Out of 2,200 men who started the campaign, only 119 were fit to fight at the end.

Foreword

It was summer in 1943 in the middle of India. We were training for the extraordinary operation that Frank describes in this book. At Brigade Headquarters we were a small band of officers and we came to know each other very well. When Frank arrived I realized I would not easily forget him. He had come to us by an unusual route, and indeed had little right to be with us. I have come, he said, from the Camouflage Pool where the sedge has withered and no birds sing. His words, quoting a poem by John Keats, had a ring of their own and defined him.

Whatever the circumstances and they varied fearfully there was always a zest and a spilling of words with Frank, in which he emptied his feelings; his heart was it seems always on display.

Read his story. It is like no other account of war. He hides nothing.

He shocks, and says things that I was afraid to say in my account of the campaign.

But he also moves. His description of the dire situation at the end of the operation reflects everything that we felt with a force that I have not seen matched exhaustion and despair and the fearful conditions, and a despising of our commanders. And he gives a picture of the land in which we moved which brings it all back. In his relations with his Gurkha troops his frankness a happy word shows him at his most unafraid. I saw how close he was to them, and saw his grief when one of them seemed to have received a fatal wound.

How deeply he felt with heart and head contending.

At the end of the operation his life took uncertain ways. What he has described as his love affair with the Chindits had fulfilled so much of him. It is all here.

I will remember Frank when other more ordinary folk have disappeared down the sink of a failing memory.

Share my delight that war has so many faces.

Richard Rhodes James Cambridge, January 2011

Introduction

Frank Baines was in many ways an improbable Chindit. At the outset of the Second World War he was a sailor, not a professional soldier, and he was homosexual. But he had a winning way with people he could care for and lead men and he was adventurous and courageous and had boundless energy. Although the Chindits faced almost insurmountable challenges and were tested to their very limits, they were not all hewn from hard rock. Many of them were simply men who were called upon to do extraordinary things; Frank was one of these.

Frank Bainess entire life was an adventure. It is not surprising that one moonlit night in early March 1944 he found himself flying in an American Dakota from India into Japanese-held Burma with a bunch of Gurkhas armed to the teeth. In this book, which he left unpublished, and which has only recently been rediscovered, Frank describes graphically how he got there, and what happened to him and the men with him. But before reading it you should know a bit about who he was, and how he came to be there, and what became of him afterwards. It wont spoil the story; it adds important background.

Born in London in 1915, Frank was the son of a prominent architect, Sir Frank Baines KCVO, who designed what is now the Headquarters of MI5 and saved the medieval roof of Westminster Hall. He also bequeathed Frank a visual eye and taste for controversy. Franks mother was the daughter of a yeoman farmer from Staffordshire. Frank himself had a blissful childhood, much of it spent in the southernmost Cornish parish of St Keverne, and some of at Oundle, a typical harsh boarding school of its time from which he fled. After school, Frank went to sea, sailing to Australia and back on one of Gustav Eriksons Finnish four masted grain ships, the Lawhill, and then working his passage to South America. At the outbreak of war, Frank enlisted as a gunner in an anti-aircraft battery in East Anglia, but was later transferred to India for officer training. He saw action as a junior artillery officer on the North-West Frontier and was then assigned to Kirkee Camouflage School, near Pune, where he became a camouflage instructor in Urdu.

Frank thirsted for action, and in June 1943 he wangled a transfer to 111 Brigade, which was to become part of General Orde Wingates crack force of Chindits. He was seconded to Brigade Headquarters as Staff Officer, Grade III (Camouflage) with the rank of Staff Captain, and thus embarked on one of the defining experiences of his life.

By that time, General Wingate had achieved fame leading a long-range penetration expedition behind Japanese lines deep inside Burma and demonstrating that the British reeling from a string of humiliating defeats across Asia, and with the enemy at the gates of India could indeed fight the Japanese in the jungle. The Chindit operations have always sparked controversy. There is even disagreement about how they acquired their nomme de guerre. Some believe it is from a corruption of the name for the mythical Burmese lion, the chinthe, which guards Buddhist temples; others that it was after a figure of Hindu mythology; others, after the Burmese word for Griffin.

If the military achievements of the Chindits in their first sally into Burma remain questionable Wingate lost one third of his men the propaganda effect was nevertheless electrifying. Winston Churchill, an ardent proponent of commando operations, recognized this and was all the more prepared to overlook Wingates very evident eccentricities. The Chindit leader often wore an alarm clock around his wrist, which would go off at times, and a raw onion on a string around his neck, which he would occasionally bite into as a snack. He liked eating boiled python. He would also go about without clothing. Lord Moran, Churchills personal physician, wrote in his diaries that he seemed to me hardly sane in medical jargon a borderline case. Notwithstanding this sometimes bizarre behaviour, Churchill took Wingate with him to the Quebec Conference with Americas wartime leader Franklin Roosevelt in August 1943, where Wingate persuaded them to equip him with a far bigger force for a second Chindit operation. It was in this operation that Frank took part.