The Last Man on the Mountain

The Death of an American Adventurer on K2

JENNIFER JORDAN

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY New York London

Copyright 2010 by Jennifer Jordan

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jordan, Jennifer, 1958

The last man on the mountain: the death of an American adventurer on K2 / Jennifer Jordan.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-393-07919-7

1. MountaineeringPakistanK2 (Mountain) 2. Mountaineering accidentsPakistanK2 (Mountain) 3. Wolfe, Dudley. 4. MountaineersUnited StatesBiography. 5. K2 (Pakistan: Mountain) I. Title.

GV199.44.P18J67 2010

796.522092dc22

[B]

2010014201

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

Charlie Houston

19132009

Last of the Golden Age

(I know that I cant keep dedicating my books to him, but I will always want to.)

Contents

Preface

I have been a journalist for thirty years, but it wasnt until I began researching The Last Man on the Mountain that I learned that history is deeply flawed. Not necessarily wrong or deliberately misleadingI simply discovered the extent to which history is sketched by the pen of its writer. In the case of Dudley Wolfe, from his ancestors in seventeenth-century Maine to recent mentions of the infamous 1939 expedition in books and articles, I found errors, omissions, prejudices, selective arguments, and deliberate falsehoods. There was also the effect of high altitude I had to take into account. In few areas is history more skewed than in Himalayan climbing: witnesses often suffer oxygen deprivation and acute mountain sickness, adding to the fog through which history is remembered and written.

As a result, I had to deconstruct the account you are about to read to its essential pieces before reassembling it. Certain irrefutable facts were questioned and some interesting skeletons fell out of the closet.

Finally, I have employed a tactic used effectively by many writers, notably Sebastian Junger in his brilliant account of the Andrea Gail s sinking off the Grand Banks in 1991, The Perfect Storm , and I did it for the same reason: it is impossible to re-create the actual dialogue of the dead with no living witnesses to the event. Therefore, in the pages that follow there are two forms of the spoken word: direct quotes, which I gathered from journals, letters, books, and witnesses, and speech given in italics, representing thoughts and conversations based on the facts I could gather, but which to my knowledge is not verbatim.

Therefore, seventy years after his death, let me introduce you to the Dudley Francis Wolfe I discovered.

Jennifer Jordan

Salt Lake City

January 2010

The Last Man on the Mountain

Prologue

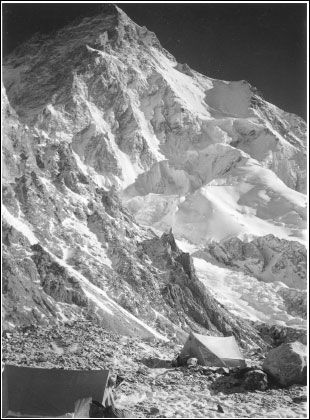

The GodwinAusten Glacier, K2, July 2002

Naked of life, naked of warmth and safety, bare to the sun and stars, beautiful in its stark snow loneliness, the Mountain waits.

E LIZABETH K NOWLTON, The Naked Mountain

Dudley Wolfes skeletal remains found in 2002. (Jennifer Jordan / Jeff Rhoads)

O n a sunny afternoon with a breeze light enough to bring fresh air into base camp but not so stiff that I needed a parka, I found myself carefully picking my way among the uneven rocks, ice towers, crevasses, and run-off rivulets of the GodwinAusten Glacier at the base of the worlds second highest mountain, K2, in Pakistan.

A few years earlier, I had learned that only five women had reached the summit of K2, and all of them were dead. Three perished on their descent, and the two that had managed to make it off the so-called Savage Mountain alive had died soon after while attempting other 8,000-meter peaks, a legendary distinction which separates the fourteen Himalayan giants which stand above the mark from the countless peaks which sit below it. Just as hikers in the Rocky Mountains aim for all of Colorados fifty-three 14ers, those mountains at and above 14,000 feet, high-altitude climbers aim for all fourteen of the Himalayan 8,000ers. High-altitude mountaineering is not a sport for the faint-hearted, and K2 is not a peak for weekend warriors. As of the 2009 climbing season, 297 people have reached its summit, while seventy-eight have died trying.

That summer of 2002, when I made my second trip to the mountain, while our team climbed, I spent my mornings working on my first book, Savage Summit , and my afternoons walking the glacier, becoming as familiar with the rocky, shifting river of ice as I was with the Wasatch Mountains in my own backyard in Salt Lake City. The glacier offered a fascinating array of odds and ends. Because of K2s topography and climatesteep rock walls and icy slopes, avalanches and hurricane-force windseverything and everyone that has ever been on the mountain eventually ends up at its base. I rarely returned to base camp from my hikes without some relic, harmless or horrific, of climbers past.

That sunny July day, while some of our team rested in their tents waiting for the mountain to shed a layer of avalanches from the latest storm, I started out on my afternoon walk. Because I had fallen into a crevasse in 2000 on our first trip to K2, my partner, high-altitude climber and cinematographer Jeff Rhoads, worried that I would disappear into another, and whenever possible accompanied me on my walks. We got further away from our tents than we ever had before, venturing down the glacier rather than our usual up it, picking our way over rock-strewn ice through the maze of ice towers. Then, about a mile off track, we turned a corner and found ourselves standing in a frozen sea of debris. While I had stumbled upon climbing rubble all summer, even the occasional desiccated body, this collection of relics was different. Unlike the bright parkas and nylon tents used by climbers since the 1970s, here was evidence from another era. Slowly we picked up fragments of canvas, leather straps, hemp rope, a rusted crampon, a tin plate and pot, even a burner plate from an old Primus stove. Then, my eyes picked something out of the rocks and rubble that I knew shouldnt be there: a bone fragment. It looked like a white pencil stub, rounded by years of exposure to the rocks and sun. I picked it up and wordlessly handed it to Jeff, fearing the worst but knowing the truth.

Yup, he said, rather casually, definitely human. See the calcified marrow inside?

I hadnt seen the marrow. He handed it back and said, Probably a piece of the ulna. I gazed at the shard in my glove and pictured the once bronzed arm from which it had come. I placed it on a piece of torn canvas, unwilling to hold it any longer.

I rejoined Jeff in picking through the old wreckage. As he went off around an icy corner, I bent to look more closely at what appeared to be a shock of long white hair. Repulsed and yet fascinated, I was considering whether to pick it up when something to the right caught my eye. There, laid out on the rocks and ice, was the very recognizable skeleton of a human being: the pelvis, two femurs, and scattered ribs.