Venice

A Literary Companion

Ian Littlewood

Copyright 2013, Ian Littlewood

All Rights Reserved

This edition published in 2013 by:

Thistle Publishing

36 Great Smith Street

London

SW1P 3BU

For Ayumi

CONTENTS

The author and publishers wish to thank the following for permission to reproduce the illustrations: Ancient Art and Architecture Collection, No. 3; Osvaldo Bhm, Venice, Nos. 17, 18; Bridgeman Art Library, No. 1; Mary Evans Picture Library, Nos. 5, 13, 14; Explorer, Paris, No. 6; Illustrated London News, No. 16; Mansell Collection, No. 12; National Gallery, No. 11; Scala, Nos, 2, 4; Scala and Ca Rezzonico, No. 10; Scala and Biblioteca Querini Stampalia, No. 7; Duke of Bedfords Collection, Woburn Abbey, No. 8.

Abhorrent, green, slippery city, D. H. Lawrence called it. Venice has never been loved by those who want to change the world. Prophets, moralists, people with missions and ambitions, tend to be impatient of its endless windings and quietly reflective surfaces. Its obsession with the past offends their sense of purpose. At once shabby and narcissistic, it attracts admirers of a different kind. The deposed, the defeated, the disenchanted, the wounded, or even only the bored, observed Henry James, have seemed to find there something that no other place could give.

Writers, many of them, they have served Venice well, and she has returned the compliment by remaining much as they described her. Plenty of cities have been preserved for us in literature; the eerie charm of Venice is that it has also, to a large extent, been preserved in reality. If James could again settle into his gondola, he would have no trouble in finding the polished steps of a little empty campo with an old well in the middle, an old church on one side and tall Venetian windows looking down. The shadowy buildings whose outlines were known to the young Casanova still rise around us as we walk by night through the Campo SantAngelo. Thomas Coryate, standing once more on the Rialto bridge, would recognize quite enough to bring back memories of his stay in 1608. Even a pilgrim like Felix Fabri would be able to renew acquaintance with churches he visited on his way to the Holy Land at the end of the fifteenth century.

For us, at the start of a different millennium, it is still possible to sit outside a caf in Venice, read their words, look up and nod in recognition. In this extravagant theatre we can with equal ease find settings for the murder of a Renaissance prince or the seduction of an eighteenth-century nun, the execution of a dissolute friar or the melancholy thoughts of a Victorian poet.

The range of material is vast. A man to visit Italy and not to write a book about it, remarked Landor. Was ever such a thing heard of? Not often, it seems. Readers will no doubt be dismayed by many omissions. Detailed accounts of processions, festivals and ceremonies have been kept to a minimum, as have descriptions of buildings. I have usually preferred byways to highways: there will be no tour of the Doges Palace, no guide to the mosaics of St Marks, no helpful words on the paintings in the Frari.

This is a guide-book, but it is only in part about the familiar city of churches, palaces and canals. From certain kinds of writing, often by the sort of people James had in mind, another Venice emerges elusive, unwholesome, perhaps a little unsafe. This other Venice owes more to myth than to brick and stone. Tainted with past iniquity, sluttish under her regal garb, she invites a kind of surrender that can tempt even the most respectable. Today we scarcely notice, for the place is ill-adapted to the urgency of modern tourism; its first requirement is time. Only to those who linger here after they have seen the sights, knowing that they should have left, does it reveal itself. In putting the book together, I have tried to recover something of this ambiguous appeal.

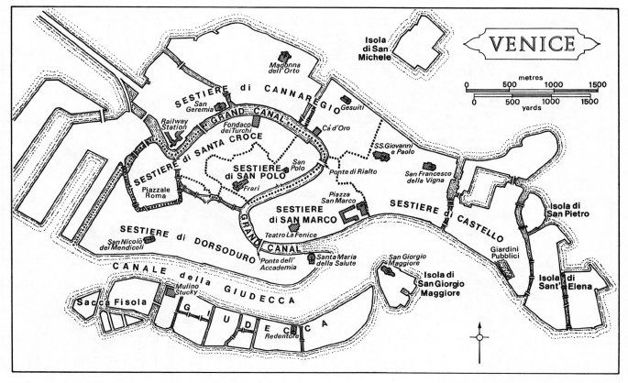

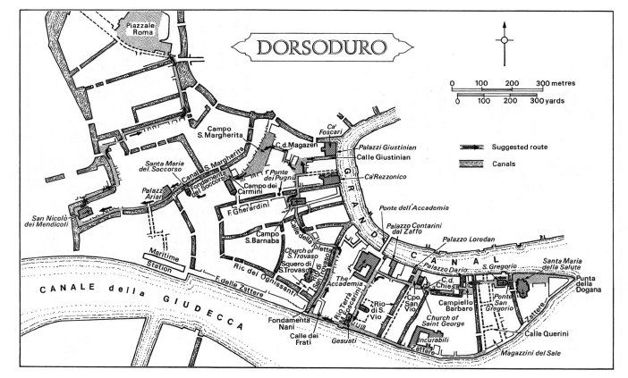

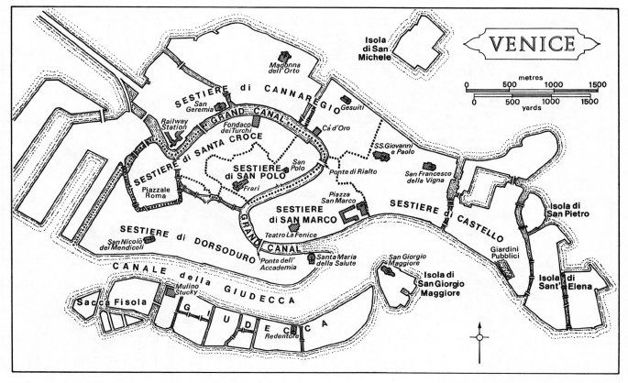

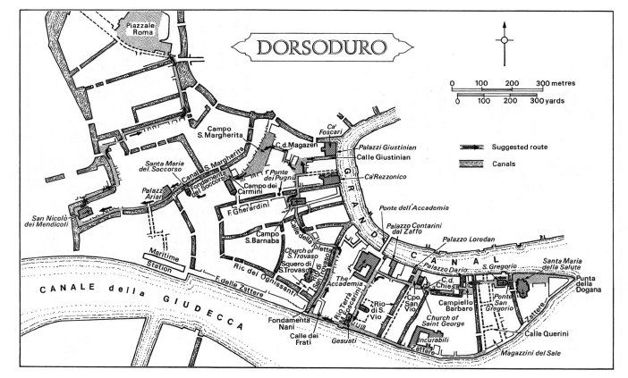

The chapters are arranged in the form of six walks which will take the determined reader into every part of the city. The final chapter touches on a few of the neighbouring islands. For those who would like to follow the suggested routes, maps are provided. Alternatively, and delightfully, one can trust to luck. Anyone who stays in Venice long enough or goes back often enough will sooner or later stumble upon everything mentioned in these pages.

Santa Maria della Salute Campiello Barbaro Rio di San Vio The Accademia Zattere San Trovaso Sottoportico del Casin Ponte dei Pugni Campanile of the Carmini Ca Rezzonico Palazzi Giustinian Calle del Magazen An Unnamed Courtyard San Nicol dei Mendicoli The Docklands Piazzale Roma

SANTA MARIA DELLA SALUTE

To enter Venice by train, claimed Thomas Mann, is like entering a palace by the back door. We shall enter by the front, San Giorgio on our left, the Doges Palace on our right, as we sweep towards the mouth of the Grand Canal. Before us, a sight that Coryate and Evelyn never saw: rising behind the customs house at the eastern tip of Dorsoduro are the stately domes of Santa Maria della Salute.

In the autumn of 1630 the plague receded, leaving almost a third of the citys population dead. Among the survivors it was an occasion for gratitude. The Republic commissioned Baldassare Longhena to build a church in honour of the Virgin. It was to be strange, worthy and beautiful, the architect declared, a building in the shape of a round machine, such as had never been seen, or invented either in its whole or in part from any other church in the city.design is an astonishing success. With its majestic cupolas and baroque faade, the Salute has become so much a part of our image of Venice that its absence from early illustrations leaves us with a sense of something incomplete.

At the entrance of the city the church greets us, according to Henry James, like some great lady on the threshold of her saloon:

She is more ample and serene, more seated at her door, than all the copyists have told us, with her domes and scrolls, her scolloped buttresses and statues forming a pompous crown, and her wide steps disposed on the ground like the train of a robe.

Prominent among the statues, above the architrave of the left-hand chapel, is a figure that caught the eye of the French poet Thophile Gautier. He had arrived in Venice in the summer of 1850 on a rainy night which allowed him to glimpse only a tantalizing shadow of the city around him. In the morning he ran to his balcony in the Hotel Europa and looked out across the Grand Canal towards the Salute. There a figure of Eve in the most gallant state of undress smiled at us from a cornice under a shaft of sunlight.

The interior of the church is dominated, as the terms of Longhenas commission stipulated that it should be, by the high altar. Horatio Brown, an Englishman who lived in Venice from 1879 and was one of its most tireless chroniclers, describes the scene at the annual festival of the Salute on 21 November, commemorating the citys salvation from the plague:

Inside the church, the devout light the candles they have carried, one taking the fire from another, and press forward after the priests up to the altar rails; there the tapers are handed over to the sacristans and placed beside the high altar, where Madonna stands, triumphing over a figure of the plague. Thousands and thousands of candles are passed over the rails until the whole space by the altar seems like one solid wall of embossed gold as the flames waver and flicker in the draught. In return for their