Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

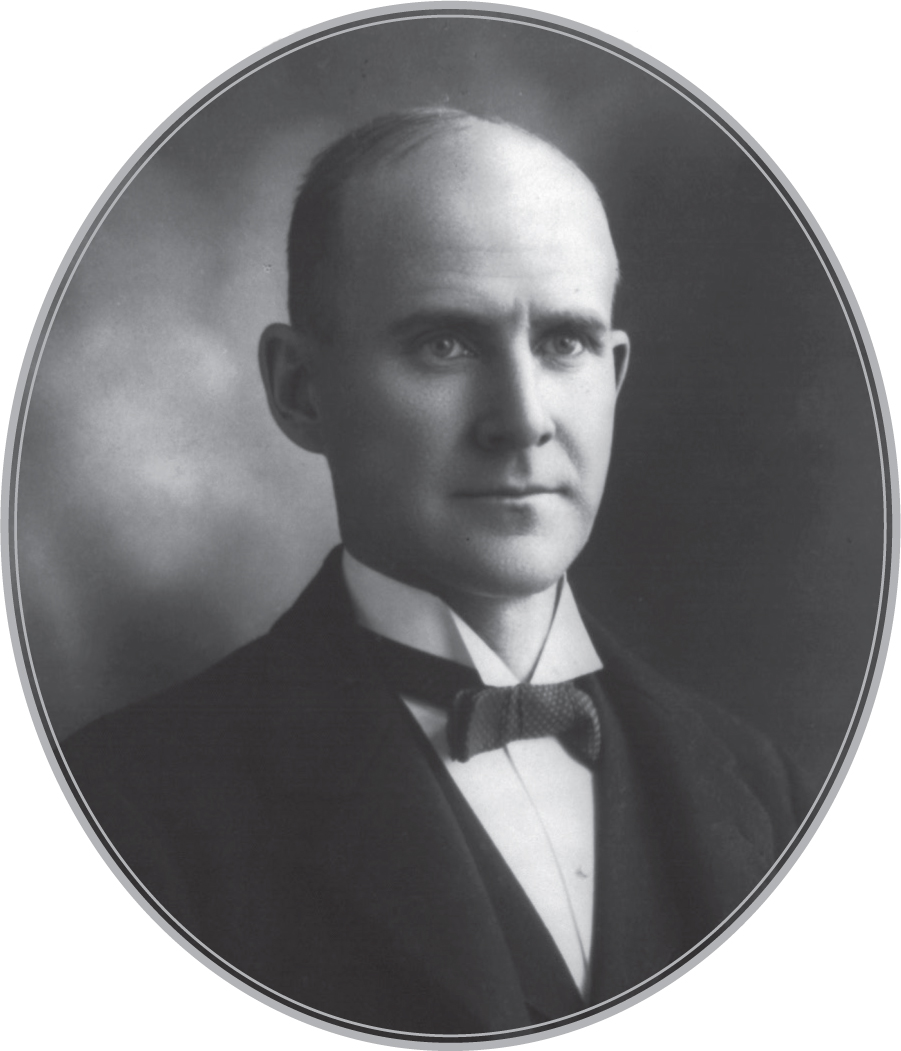

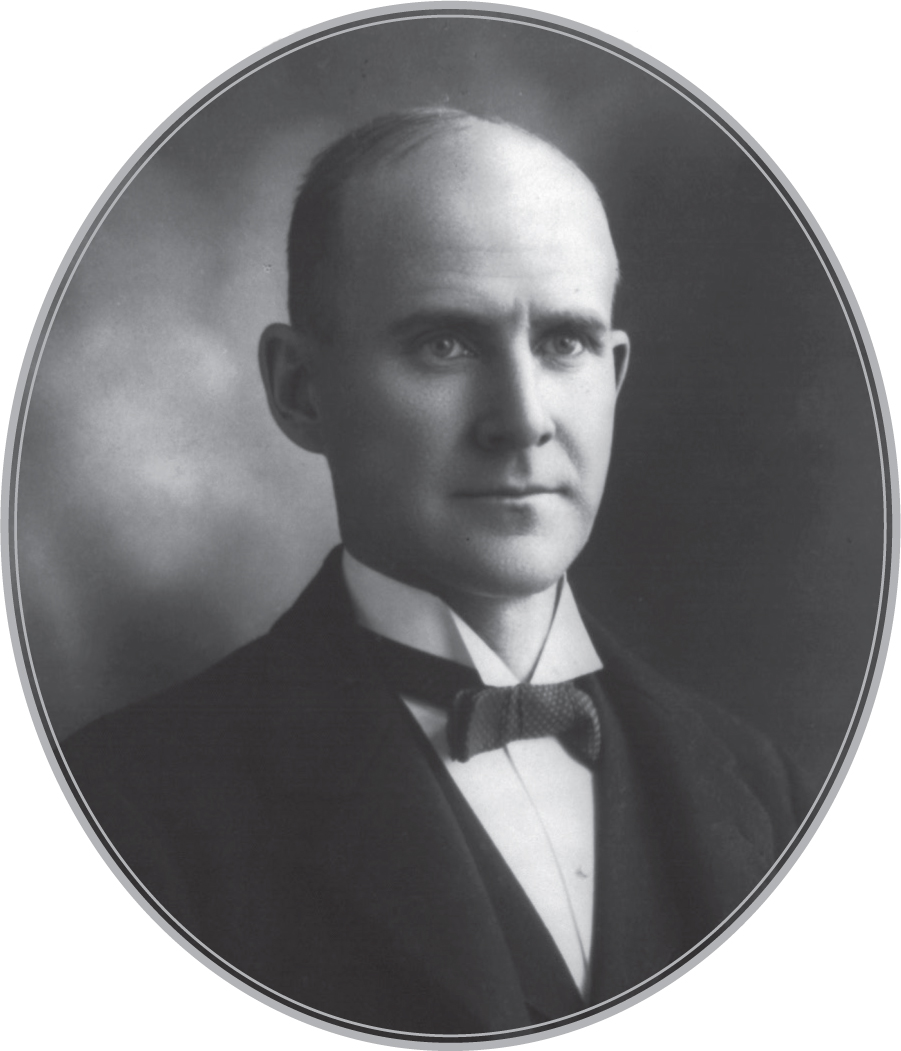

Eugene Victor Debs

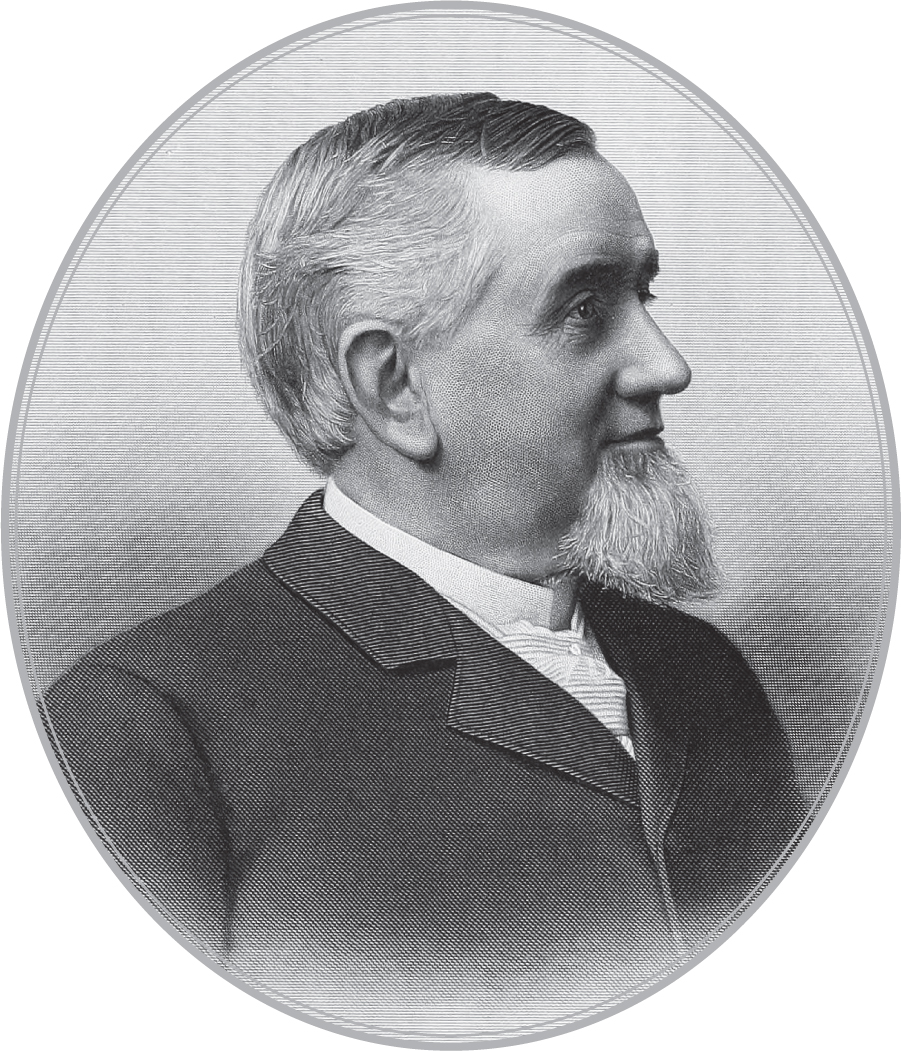

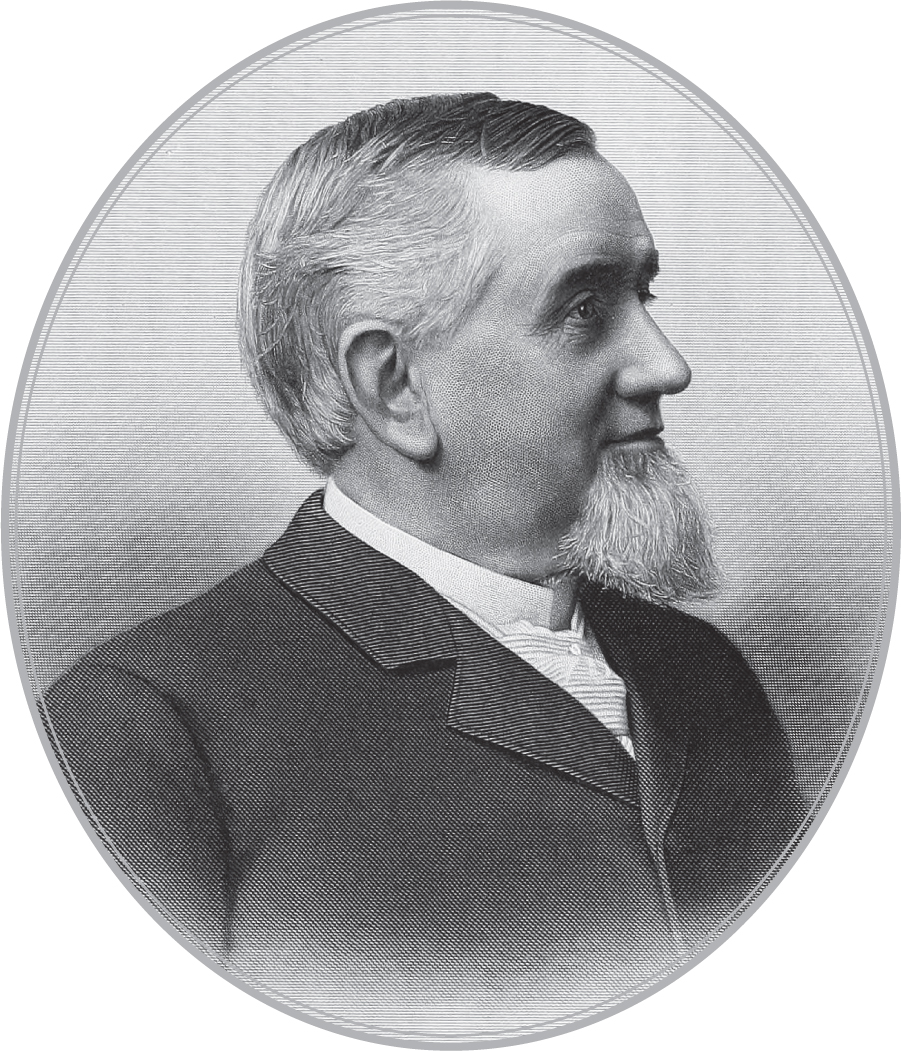

George Mortimer Pullman

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

We have been brought to the ragged edge of anarchy.

U.S. A TTORNEY G ENERAL R ICHARD O LNEY

.jpg)

.jpg)

On a May morning in 1893, President Grover Cleveland looked out on the most astounding metropolis ever built, the fabulous White City of the Worlds Columbian Exposition. Staring back were the half-million citizens who had crowded into the fairgrounds on Chicagos South Side to view the wonders of the age.

Cleveland was a burly man with a shoe-brush mustachehis nephews called him Uncle Jumbo. In his speech, he praised the stupendous results of American enterprise and congratulated the nation for having produced men who rule themselves. Few in the immense throng could hear himthey applauded anyway.

A hopeful gleam of sunlight stabbed through the clouds and flashed from the golden telegraph key in front of the president. Clevelands pudgy finger tapped the button, setting in motion a huge dynamo that transformed the fair into a marvel.

Electric fountains made water dance a hundred feet above the heads of the spectators. Flags unfurled in unison. Salutes boomed and echoed from the guns of warships. Whistles shrieked. A shroud fell to reveal the enormous personification of the Republica sixty-five-foot gowned figure in glorious gold leaf that would be known to all as Big Mary. The mob of onlookers screamed their approval.

* * *

They came by the millions and tens of millions. Almost one in every five Americans made the trek to Chicago that summer for the worlds fair. Their reaction to the spectacle was summed up by a diarist who wrote: My mind was dazzled to a standstill.

Almost all who came, came by train. Those who could afford it rode a Pullman car, the epitome of luxurious travel. A Pullman sleeper offered room to spread out, elegant service, and the delicious pleasure of status. Fairgoers were headed to Chicago to shake hands with the future, and in the Pullman car the future seemed to be reaching out to greet them.

Those who had not had the privilege of riding on one could take in all the latest models at a display mounted by the Pullmans Palace Car Company in the fairs Transportation Building. The carved rosewood, Axminster carpets, polished brass, fringed valances, and cascades of curtains and draperies beloved by Victorians all made Pullman travel an adventure in hedonism. By day, a Pullman was a fantastic parlor room on wheels. When night came, a smiling porter turned a pair of facing seats into a bed and produced a second berth from a compartment along the ceiling. He arranged heavy curtains, pristine damask sheets, and mahogany partitions, transforming the car into a comfortable dormitory.

The lucky few, railroad magnates or politicians, might be given a guided tour of the exhibit by the man himself, George Mortimer Pullman. The sixty-two-year-old progenitor of these marvels was one of Chicagos richest entrepreneurs. Many fair visitors could remember the stagecoach days when no man traveled on land faster than the pace of a team of horses. Long train trips had demanded new technologyand Pullman had provided it. The sleeping car had become so closely associated with one company that it was coming to be called simply a pullman. The understated booklet distributed by the company gushed a bit when it called the inception of the Pullman firm, now valued at $60 million, one of the centurys great civilizing strides.

Pullmans name and face were well known across the countryhe had made sure of that. His wide, nearly unlined features were those of a tired baby. His hair had gone white and he wore on his chin a goat-like tuft of beard, which boys of the day called a dauber. His imperious eyes were always sizing up.

George Pullman represented a relatively new type in America, a businessman. He was a man of affairs, a man on the lookout for the new. A businessmans key skill was organizing an enterprise and raising the money to fund it. Pullman knew how to gather resources, command men, and negotiate deals. Early in his career, he had begun to list his profession simply as gentleman.

The assertion by his publicity machine that George Pullman had invented the modern sleeping car was less than accurate. Most of the credit went to a man named Theodore T. Woodruff, an upstate New York wagon maker. But the mechanics of the car had evolved over decades, and Pullman had introduced his share of innovations.

What was beyond doubt was that Pullman had devised the most efficient system for making money from the sleeper. He saw each car not as a product but as a revenue stream. He retained ownership and allowed the various railroads to haul the cars under contract. The railroads profited because the luxury cars attracted customers. Pullman profited even more as each passenger paid him a hefty fee for the upgrade.

Pullman also understood that monopoly was the path to profit, and by 1893 he was well on his way to absorbing all other sleeping-car manufacturers into his company. A Pullman brochure boasted that the company employed fifteen thousand and ran its cars over enough track mileage to stretch five times around the circumference of the earth.

Pullman asserted that he was free of the fever of rapid wealth-getting. He could afford to be. He and his wife, Hattie, floated among the highest tiers of Chicagos social heaven. An observer called him a lordly man. Reserved of speech, he let his possessions speak for him.

* * *

In 1831, the year George Pullman was born in a remote hamlet in the western end of New York State, a group of Americans at the other end of the state were taking a ride on Americas very first steam-powered passenger railroad. It was the beginning of the most stunning transformation in the nations history. During Pullmans lifetime, private corporations laid more than 175,000 miles of rail, including five transcontinental lines.

Americans take to this contrivance, the railroad, Ralph Waldo Emerson had observed, as if it were the cradle in which they were born. In the three decades since the Civil War, the railroads had proliferated into a great tangle of trunk lines and branch lines through the East and Middle West. When builders pounded the golden spike at Promontory Summit, Utah, in 1869, they tied together a continent. The New York Central main line ran from the Atlantic coast to Chicago. The mighty Pennsylvania system extended an arm across the Keystone State and spread its fingers into Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and beyond. The Southern Pacific, the Union Pacific, and the Santa Fe had erased the frontier. Enormous combines had gobbled individual rail lines, and the railroad corporations had become the most extensive business enterprises in history.

.jpg)

.jpg)