The British Navy in the Caribbean

John D. Grainger

THE BOYDELL PRESS

John D. Grainger 2021

All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner

The right of John D. Grainger to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

First published 2021

The Boydell Press, Woodbridge

ISBN 978 1 78327 589 2 hardback

ISBN 978 1 80010 083 1 ePub

The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd

PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK

and of Boydell & Brewer Inc.

668 Mt Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 146202731, USA

website: www.boydellandbrewer.com

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The publisher has no responsibility for the continued existence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate

Cover image: The Lapwing Captn Barton, capturing a French Frigate, and Sinking a Brig, in the West-Indies

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Abbreviations

ADM Admiralty documents

CO Colonial Office documents

CSPCalendar of State Papers

NRS Navy Records Society

TNA The National Archives

Introduction

The Caribbean Sea is sometimes described as an American Mediterranean, As by D.W. Meinig, Transcontinental America, 18501915, vol. 3 of his The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History, New Haven, 1998, 354. but this is to ignore the fact that the Caribbean is actually a reverse image of the Mediterranean Sea, at least in geographical terms. On the other hand, both seas, until the Suez and Panama canals were constructed, could only be entered from the Atlantic, though whereas the Mediterranean has only one entrance, at the Strait of Gibraltar, the Caribbean has multiple entrances between a whole string of islands. It therefore hardly helps to describe the Caribbean in Mediterranean terms, though they were both, in a curious element of similarity, the recipients of waters from a giant river, the Mississippi (plus the Rio Grande and the Orinoco) and the Nile, plus the Black Sea rivers.

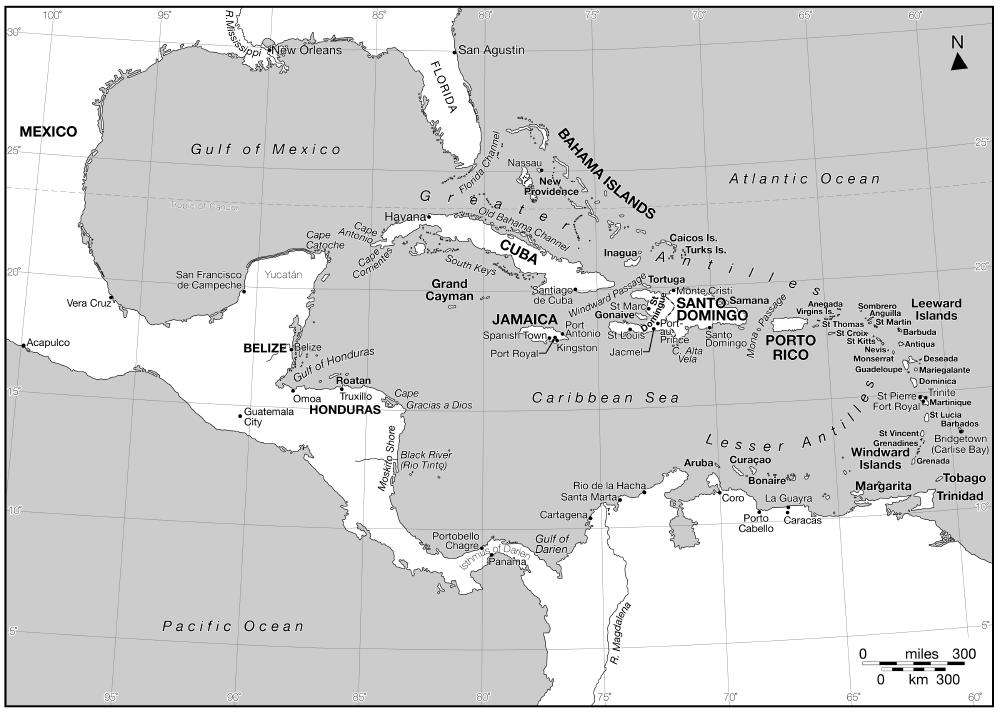

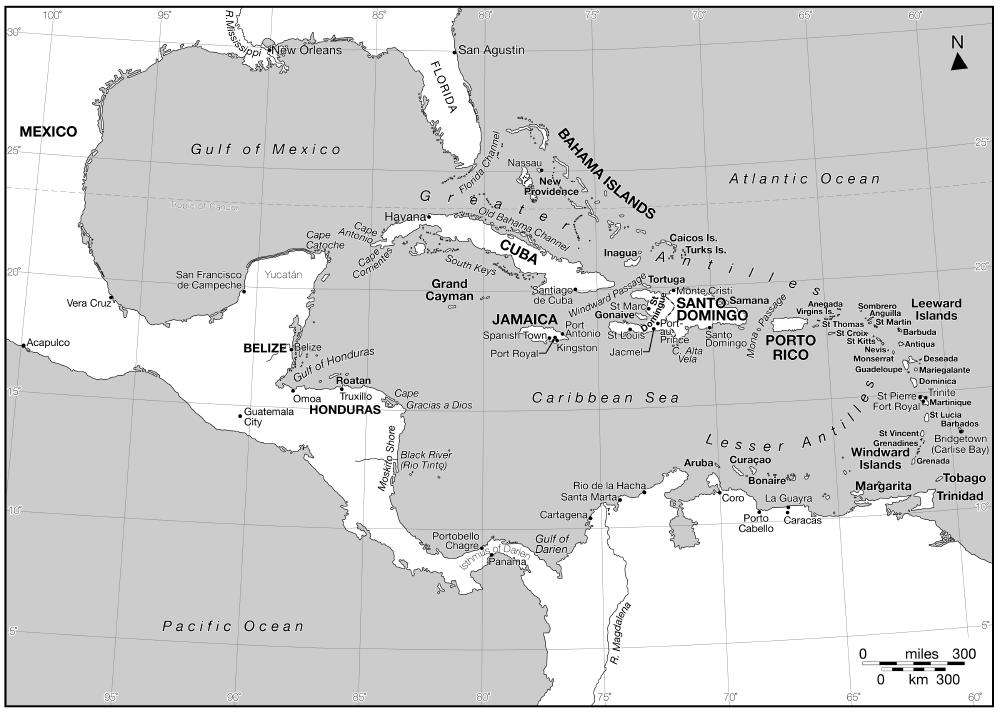

The two great continents of North and South America are linked by the narrow Isthmus of Panama, which encloses the Caribbean at its western end. At the eastern end of the sea there is a string of relatively small islands, the Lesser Antilles and the Bahama Islands, between which there are numerous passages, though not all were favoured by sailors. The distance between the two extremes is perhaps 3000 kilometres. The sea itself is divided into two parts by the long narrow island of Cuba and the other large islands of the Greater Antilles. The north part is the Gulf of Mexico, and the south is the Caribbean Sea proper.

This geographical layout is the clue to understanding many of the peculiarities and particularities of Caribbean maritime history. The openings on the east, through the many islands, scattered between Guiana and Florida, allow a strong current to flow from east to west out of the Atlantic and into the Caribbean; the solid barrier of the Isthmus and Central America forces the current to turn north and flow out of the Caribbean between Cuba and Yucatn; the closed nature of the Gulf of Mexico diverts the current once more past the north coast of Cuba, flowing this time west to east, and it exits the sea between Hispaniola and Florida and swings north to flow between the Bahama Islands and Florida; at this point it becomes the Gulf Stream, to which most Western Europeans are extremely grateful for their equable climate.

Just about all the islands had been populated for several thousands of years. The Greater Antilles were populated by Arawak people who were comparatively numerous agriculturalists; the Lesser Antilles were populated mainly by Caribs who were also agriculturalists, but also fishermen and hunters, and were regarded as fierce warriors. The Caribs had been expanding slowly along the line of the Lesser Antilles out of South America for some time, and a certain degree of enmity existed between Arawaks and Caribs. The Caribs themselves later had a reputation for fierceness and even gave their names to cannibalism, though this was a rare occurrence, and their fierceness seems to have come mainly from the fact that they were being threatened in their homeland by the even fiercer enemies of the European invaders, and what they saw happening to the Arawaks at Spanish hands.

Next page