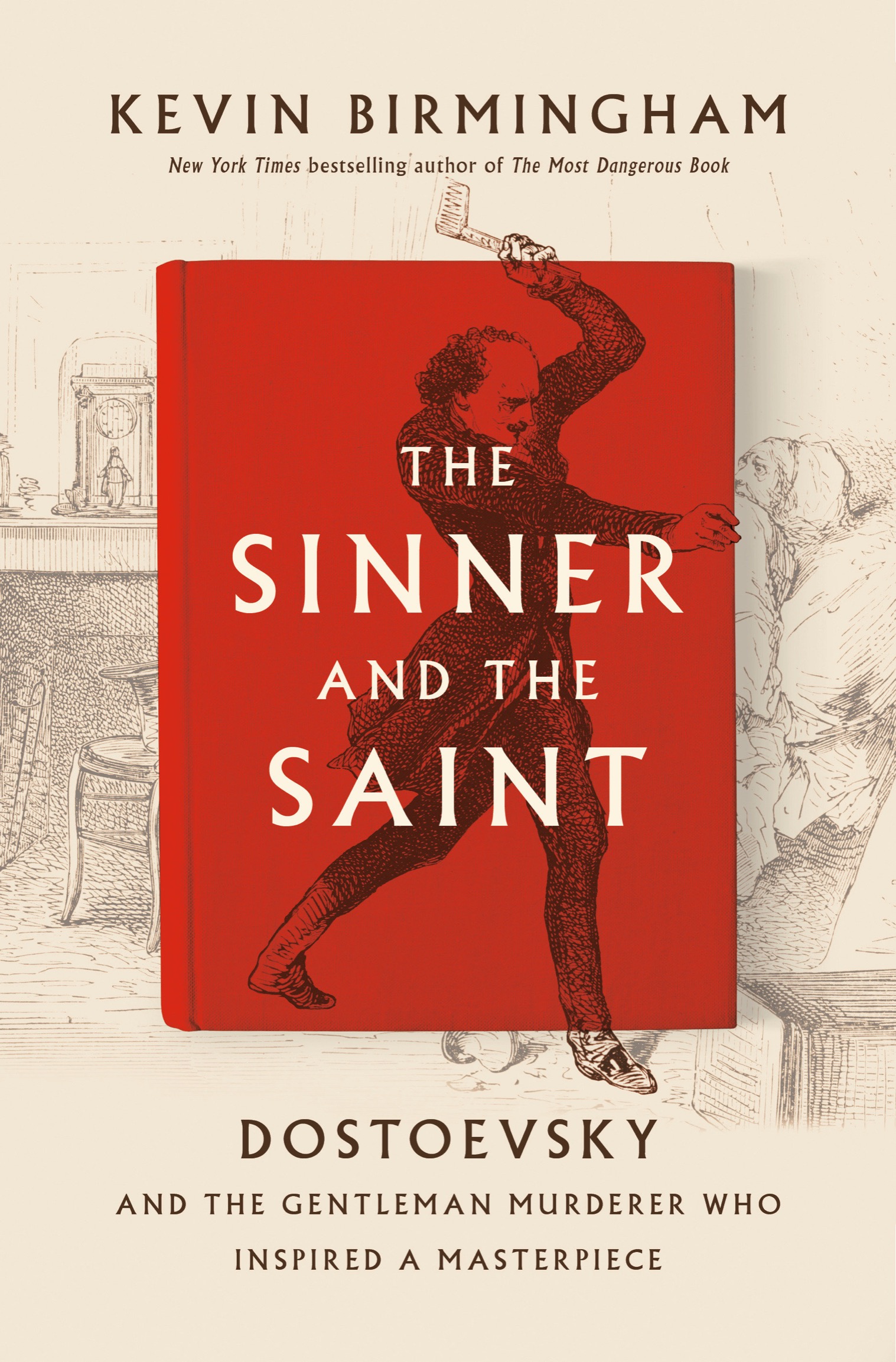

ALSO BY KEVIN BIRMINGHAM

The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyces Ulysses

PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2021 by Kevin Birmingham

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

constitutes an extension of this copyright page.

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

Names: Birmingham, Kevin, author.

Title: The Sinner and the Saint : Dostoevsky and the Gentleman Murderer Who Inspired a Masterpiece / Kevin Birmingham.

Description: New York : Penguin Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021015314 (print) | LCCN 2021015315 (ebook) | ISBN 9781594206306 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780698182882 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Dostoyevsky, Fyodor, 18211881. Prestuplenie i nakazanie. | Dostoyevsky, Fyodor, 18211881Sources. | LCGFT: Literary criticism.

Classification: LCC PG3325.P73 B53 2021 (print) | LCC PG3325.P73 (ebook) | DDC 891.73/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021015314

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021015315

Cover design: Stephanie Ross

Cover images: (main art) Murder in the Passage du Cheval Rouge, c.1835 (engraving), Jean Adolph Beauce, Bridgeman Images; (book) Javid Isgandarov / Shutterstock

Designed by Amanda Dewey, adapted for ebook by Cora Wigen

pid_prh_5.8.0_c0_r0

For Julia and the future

A Bloody Enigma

Theres an evil spirit here. The voice broke through every now and then, among various notes and ideas for the story. A young man, looking back upon his crimes, concludes that an evil spirit compels him. How otherwise could I have overcome all those difficulties?

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky was writing in a hardcover notebook. His candle had burned down to a nub, and the hotel staff refused to give him another one until there was nothing left. They had been instructed to ignore him, to stop cleaning his clothes, to stop serving him dinner. Dostoevsky would wander around Wiesbaden in the early evening, pretending to have someplace to eat, and return at night to fill his notebook pages with bits of dialogue and plot overviews and reminders. Very Important. Dont forget.

There were fully imagined passages and pages of budding ideas. He underlined key words and phrases. He squeezed additions in the margins or between lines. He crossed out entire paragraphs that seemed blunt or excessive. He drew sketches on the pages, as if he couldnt put his pen down even when he wasnt writing. Drawings of churches and foliage. The faces of his characters appear, shouting and smiling and blending into crosshatched shadows with lines of text edging around them. Sometimes the murderers voice would burst out. Is it really going to continue eternally, eternally! the voice shouts. Oh, how I hate them all! How I would like to take them all and slaughter them all to the last one. He crossed it out.

Dostoevsky was determined to tell a murder story from the murderers perspective, and his character couldnt be a monster. He would have flashes of anger, and he would be bitter and proud, but he would be sensitive, compassionate, and bookish. He would want to put ideas into action. He would believe that one bold, extraordinary act could change everything. He would not fantasize about slaughtering people. No. The murderer would be chilling because he wants so desperately to be good. When I become noble, the murderer says, the benefactor of all, a citizen, I will repent.

Readers would have to be disturbed but not repulsed so that they could get close to a murderers mindcloser than they had ever been beforeand yet continue reading. There is an evil spirit here, its true, but a spirit that settles into something insidious and mundane, a slithering way of thinking. It turns out that I acted logically, Dostoevsky had the murderer conclude. But that wasnt quite right either, and the strange alchemy of reason and bitterness, idealism and darknessthe quixotic and the wickedbecame more difficult to handle as time went on.

It was September 1865. For more than a month, Dostoevsky had been staying at the Hotel Victoria in Wiesbaden, Germany, where he had lost all his money at the roulette tables. He wrote to Ivan Turgenev, thinking that a fellow novelist, a fellow gambler, would send money. I am disgusted and ashamed to trouble you. But except for you I have absolutely no one at the present moment to whom I could turn. He was suffering from a fever that left him shivering at night, and the hotels proprietorsurely familiar with cases like thishad begun threatening to summon the police. Dostoevsky was trapped in a hotel beside Wiesbadens railway station, broke, ill, and humiliated. His murder story was his only way out.

Dostoevskys career until 1865 could not have been more turbulent. In just four years, he had gone from being a literary sensation to a convict in chains exiled to Siberia. He was only twenty-three years old when he was celebrated throughout St. Petersburg as Russias next great writer while his first work of fiction, a novella called Poor Folk, had not even been published yetit was circulating as a manuscript. A swift downfall followed: rushed stories, negative reviews, rejection from the very people who had lionized him. His involvement in political circles led to his arrest and exile in 1849. He spent four years in a hard-labor prison camp and five years in a Siberian army battalion, and he would remain under surveillance until shortly before his death.

He knew better than anyone the high stakes of being a writer in tsarist Russia. Writers were suspect. All reading material, including newspapers, required prepublication approval from censors. Books were frequently banned, and private presses were forbidden. The path Dostoevsky had chosen was particularly treacherous at mid-century, when Russia found itself caught between the liberalism sweeping Europe and the empires entrenched authoritarian rule. By the 1860s, disputes about the empires direction were acrimonious. Russia, Dostoevsky declared in 1861, was becoming a nation divided into two hostile camps.

Dostoevsky returned to Petersburg in 1859, after a decade in exile, and published his account of Siberian prison life, Notes from a Dead House, to great acclaim. He felt resurrected. He used his newfound clout to be his own editor in his own magazine. In less than five years, he and his brother Mikhail founded two journals and watched each of them collapse. One was crushed by debt, the other by order of the tsar.

Now, alone in his hotel room, he was forty-three years old. His wife and his beloved Mikhail had both died the previous year, three months apart. He was fifteen thousand rublesseveral years incomein debt, none of his great novels had yet been written, and he was suffering from powerful epileptic seizures. Each one left him depressed and lost in a mental fog for days or weeks. It was increasingly difficult to write.