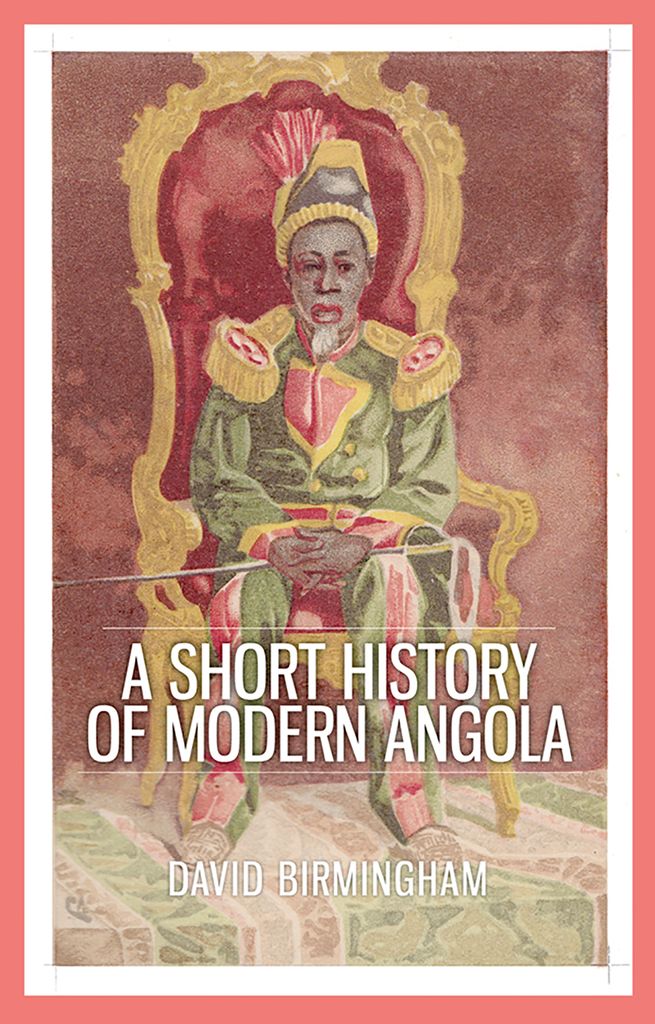

A SHORT HISTORY OF MODERN ANGOLA

DAVID BIRMINGHAM

A Short History of Modern Angola

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

OxfordNew York

AucklandCape TownDar es SalaamHong KongKarachi

Kuala LumpurMadridMelbourneMexico CityNairobi

New DelhiShanghaiTaipeiToronto

With offices in

ArgentinaAustriaBrazilChileCzech RepublicFranceGreece

GuatemalaHungaryItalyJapanPolandPortugalSingapore

South KoreaSwitzerlandThailandTurkeyUkraineVietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Copyright David Birmingham 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available David Birmingham.

A Short History of Modern Angola.

ISBN: 9780190271305

eISBN: 9780190613457

CONTENTS

The history of Angola falls into three parts. In medieval times the region was ruled by kings who controlled the religious art of rain-making and the magic art of iron-smelting. The three early modern centuries were dominated by Brazilian conquistadores for whom Angola was the Black Mother which supplied millions of plantation slaves. The nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw the rise of a modern colony covering a land area of half a million square miles. Between 1820, when the modern era began, and 1975, when the formal colonial era ended, Angolas coast, and in time its whole territory, was administered by Portugal. This modern period is dominated by great flows of migrant peoples. In the nineteenth century over half a million Africans were taken from their homes as slaves, or as conscript labourers, to work the coffee estates of the newly independent empire of Brazil or the cocoa plantations of the little island-colony of So Tom. The beautiful harbour-city of Luanda became the capital of a spreading Angolan colony ruled by governors appointed by the Saxe-Coburg kings and queens of Portugal. In the twentieth century the flow of peoples was reversed and up to half a million European migrants arrived in Angola. Many came from the back lands of northern Portugal, or the Atlantic islands of Madeira and the Azores, seeking prosperity in Africa. Others were later conscripted as foot-soldiers to resist the rising tide of anti-colonial nationalism which swept through Africa in the 1960s. Colonial governors from Portugals army and navy were appointed by republican dictators who ruled in Lisbon after the monarchy had been overthrown in 1910. In 1975 change occurred again and the white population of Angola flowed back to Europe leaving African nationalists to struggle for control of their rich but unequally shared economic heritage.

The kingdom from which Angola gained its name was initially ruled by the Ngola dynasty whose rocky fortress lay above the valley of the Kwanza River. It was first described to the outside world by an early Jesuit mission established there in the 1560s. The wealth of the kingdom was epitomised by the coastal fisheries of Luanda Island which produced a regional shell currency. Spiralled shells were used in the Kongo kingdom for such social payments as bride wealth and for political taxes or judicial fines. The Ngolas northern neighbour was the ruler of this larger and more powerful kingdom lying south of the Congo River estuary. The medieval customs and traditions of Kongo were recorded by Christian missionaries and by Jewish traders. The king received feudal-type tribute from half-a-dozen provinces whose governors soon adopted European titles such as marquis or duke. To the south of the Ngolas domains lay the great Benguela highland, ruled by a dozen merchant kings, and a coastline of Atlantic fishing villages. Today these three regions, north, central and south, are part of the Republic of Angola.

The Atlantic shipping bridge which linked Angola to South America grew slowly when Portuguese colonies called captaincies were established in Brazil in the 1530s and cane sugar became the worlds most valuable traded commodity. Initially Atlantic merchants bought their supply of Brazilian plantation slaves from the kings of Kongo. These kings, one of whom sent his son to Rome to be trained as a bishop, received European craftsmen and priests to build and staff churches which enhanced the prestige of their capital city, San Salvador. They paid for expatriate missionaries by selling black labourers. As this trade in slaves grew, a Brazilian-type captaincy was created in the 1570s at Luanda in Angola. This African estate was granted to the Jewish grandson of the Portuguese explorer Bartholomew Dias. His role as supreme lord-proprietor of Angola was later replaced by military captains appointed by the Habsburgs who came to rule Portugal, as well as Spain, in the 1580s. These conquistadores overran the Kwanza River basin, levied tribute in male and female slaves from local headmen, and gained wealth by selling their captives not only to the infant plantations in Brazil but also to Spains great American dominions.

The Atlantic trade was greatly enhanced by the Dutch development of modern capitalism and the invention of joint stock companies which gained a major stake in Portugals East Indies and later also in Brazil. Dutch shipping carried a significant share of Atlantic produce to northern Europe. In the 1640s the Dutch empire, which gained fortresses in both West Africa and South Africa, temporarily held the great Angolan fortress at Luanda from which it supplied slaves to rich sugar colonies which the Dutch had captured in northern Brazil. By the eighteenth century new discoveries of American mineral wealth required ever more slave miners. Brazilian wealth grew in leaps and bounds with the discovery of first gold and later of diamonds. Angolas slave catchers were driven to extend their commercial networks deeper into the interior of Africa. The old conquistadores were replaced as suppliers of slaves by Europeanised African merchants, sometimes referred to as Creoles. In Angola black, Portuguese-speaking, Creoles were predominantly traders who imported manufactured goods, particularly cotton textiles from Portuguese India. A more corrosive form of payment for slaves was the addictive supply of tobacco and rum from Brazil and of rough red wine from Portugal. From the early nineteenth century the commercial sphere of informal influence dominated by Portugal, and by the Angolan Creoles, gradually evolved into a formal colonial territory, albeit one with fluctuating frontiers which were not finally agreed to by rival European powers until the 1920s.

The use of names in Angola presents a problem. Geographically the countrys southern neighbour, Namibia, was for about a hundred years known as South-West Africa. On the eastern border, Zambia was once called Northern Rhodesia, and Katanga was briefly known as Shaba. The territory to the north of Angola went through even more changes of namethe Free State, the Belgian Congo, Congo-Kinshasa, Zare, most recently the DRC. In this book it is referred to throughout as Congo. This needs to be distinguished from a French colony variously known as Middle Congo, French Congo, and Congo-Brazzaville. Another possible cause of confusion concerns the name of different ethnic groups. I refer to the Kikongo-speaking people of the north as Kongo and the Umbundu-speaking people of the south as Ovimbundu. I have, improperly, called the Kimbundu-speaking people of the centre Kimbundu rather than using the more correct Mbundu. Like every other historian of Angola I had great difficulty finding a term to use for Africans with a greater or lesser degree of Portuguese culture. I have controversially called them Creole with apologies to all those who have tried to find alternatives. In the wider historical literature the term Creole has meant black in West Africa and white in the West Indies. It has sometimes been used to refer to the Luso-Africans of old colonial towns, to mixed-race Angolans with Portuguese genes as well as Portuguese culture, and even to the