First published in the United States of America in 2018 by Chronicle Books LLC.

First published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by Thames & Hudson Ltd.

2018 Quarto Publishing plc

Conceived, Designed and Produced by Quid Publishing, an imprint of The Quarto Group

The Old Brewery, 6 Blundell Street,

London N7 9BH, United Kingdom

T (0) 20 7700 6700 F (0) 20 7700 8066

www.QuartoKnows.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-4521-7529-4 (epub, mobi)

ISBN: 978-1-4521-6991-0 (paperback)

Chronicle books and gifts are available at special quantity discounts to corporations, professional associations, literacy programs, and other organizations. For details and discount information, please contact our premiums department at or at 1-800-759-0190.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

Introduction

Open a traditional paper map and mysteries await. The labyrinthine folds and arcane symbols reveal so much more information than any GPS could. They provide a broad birds-eye view, not only of the geography, but also the culture and history of a place. Comparing a traditional map to a GPS map is like comparing the view from a mountaintop to the view through a tunnel. A GPS map can tell you nothing of the historical idiosyncrasies of its respective cultures or creators, nor can it show the patterns of towns as they grew from an ancient tangle of dwellings to huge urban grids.

My own journey through the history of hand-drawn maps began with an ill-fated job in a gallery selling antique prints (I lasted three weeks). I became fascinated by the crude colors and intriguing details left by the great 17th-century cartographers John Speed and John Ogilby. Their personalities ring out clearly from their work. Hand-drawn, their maps depict features they considered important, with the rest left out. A cartographer always makes maps for a reasonto show boundaries, to display ownership and wealth, to keep people out, or things in, or simply to document. The details we see on maps are the result of this process, presented in a perfect combination of information and design.

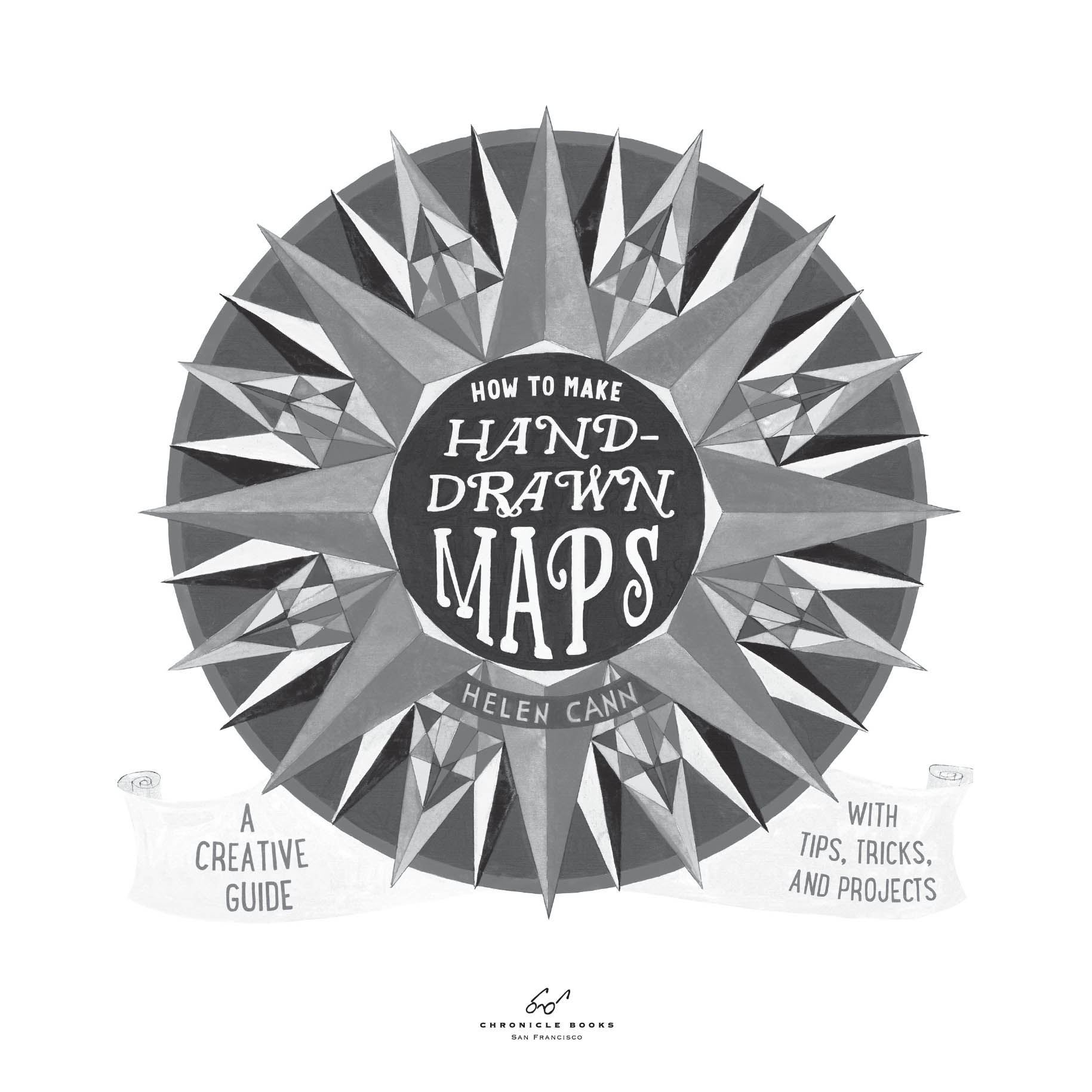

About this book

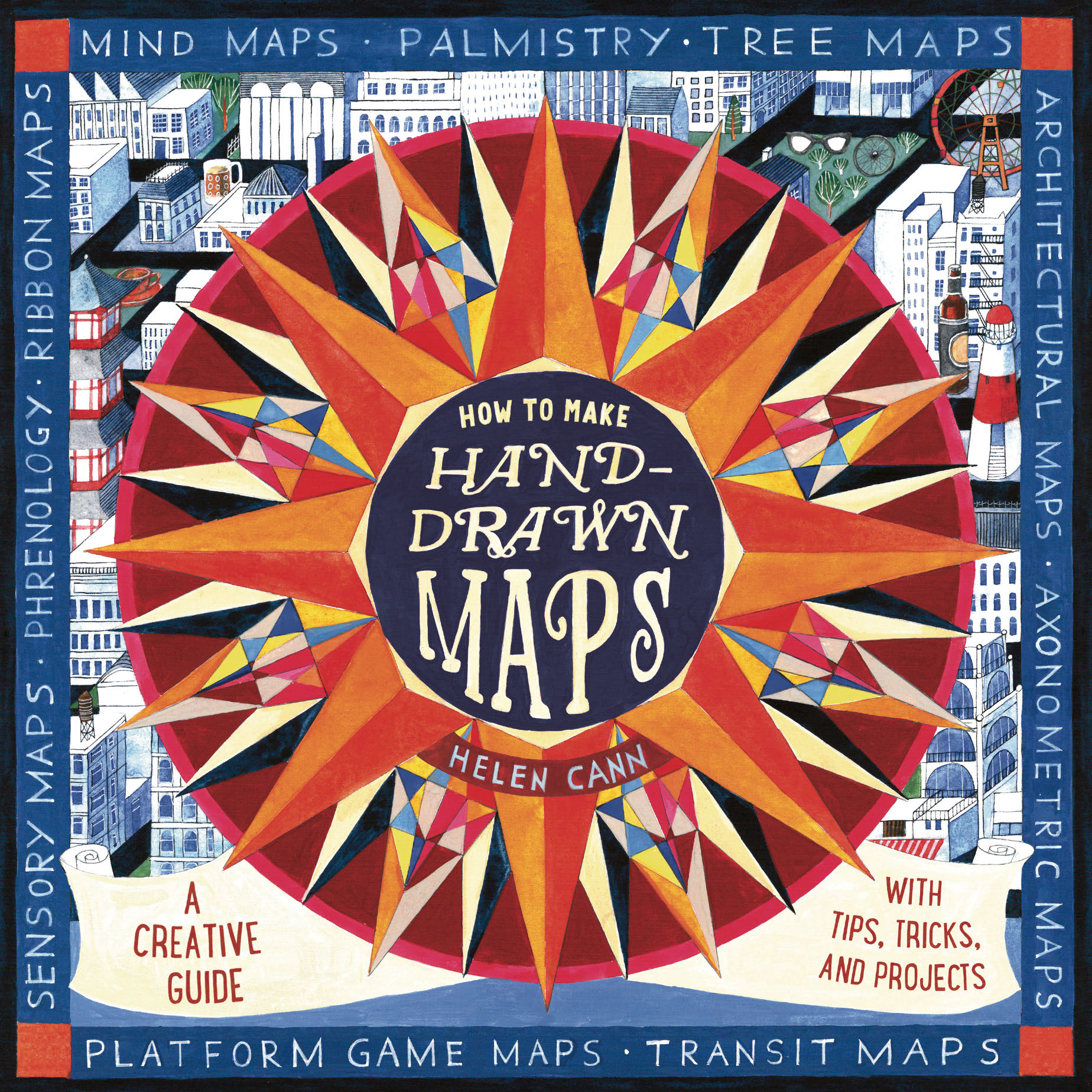

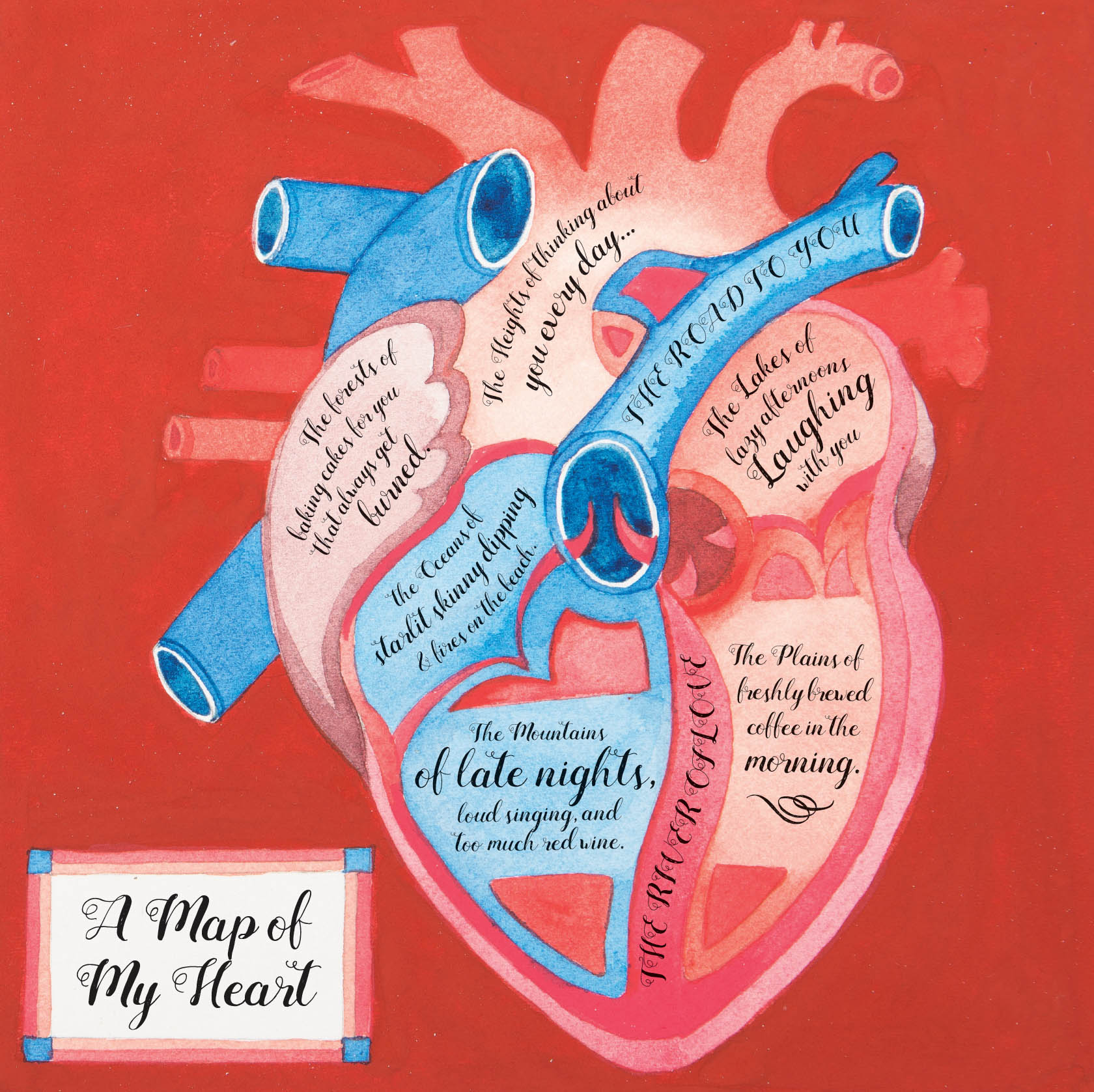

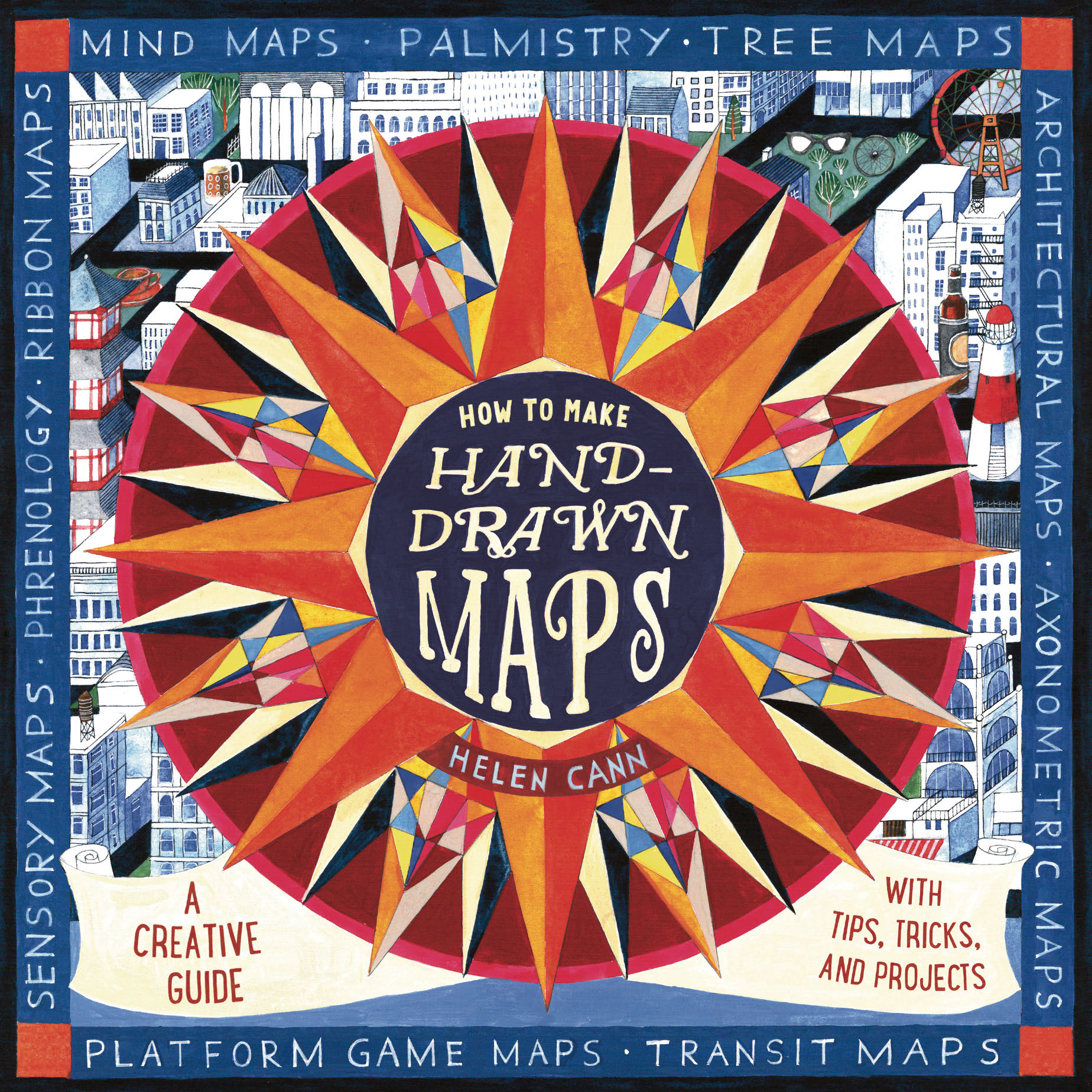

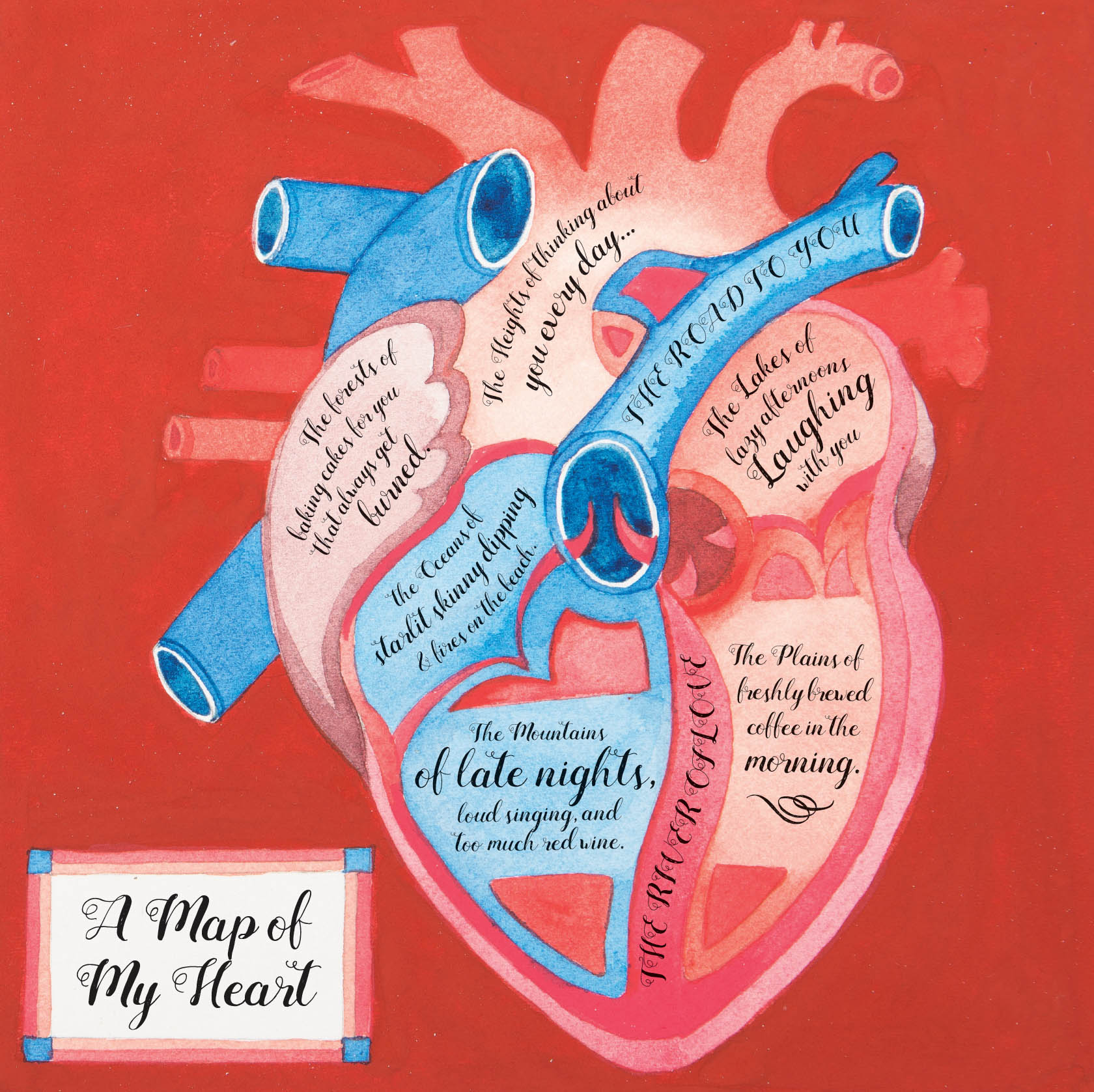

In this book you will learn how to draw basic maps in your own personal way. You will discover how to create compass roses, cartouches, and symbolsthe basic tools you need to become a mapmaker. Then, we will look at different ways to present a 3-D landscape on a 2-D planefrom architectural blueprints to subway maps, axonometric grids to treasure maps. We will move on from geographical regions to look at mapping conceptscharting thought processes, families, and anatomy.

Each chapter has an exercise for you to try yourself. Sometimes these might involve having to do some research. You might have to get outside for a walk. Some exercises need graph paper or require premade templates, which you can find at the back of this book.

You will, of course, need something to draw with. Every map in this book starts with a simple line drawing, but often in my examples I have incorporated color. Feel free to experiment with different materials in your own creations. A couple of exercises recommend the use of compasses, rulers, and protractors, but since these are hand-drawn maps, and not exercises in technical precision, these can also be done by eye.

The last chapter suggests a number of simple ways in which you can incorporate hand-drawn maps into practical projects. Hand-drawn maps are a perfect means of providing directions, remembering your travels, or simply expressing yourself.

Among my own examples you will find mentions of other noteworthy cartographic artworks for you to research. As further inspiration, there are profiles of five international cartographic artists. Creating hand-drawn maps is in itself a personal journey, so let your personality shine through. When producing your own maps, highlight the features that matter to you. Whether youre mapping a real or an imagined landscape, map your world in your way.

A Brief History of Maps

The art of mapping has a long and rich history. Maps have been a vital part of communication from the moment people wanted to describe to each other the details of a place, or show how to get somewhere. Examples of early mapmaking abound. Stone Age maps of the constellations are daubed on cave walls in France. Beautiful wood-carved maps from Inuit Greenland show the formations of the coastline. These tiny, tactile map sculptures would have fitted neatly into a sealskin pocket and been useful on any hunting expedition. Polynesian seafarers who settled the Pacific made maps of the seas with sticks, shells, and palm fronds, all tied together. Obviously, there is a strong need to visually describe places.

As civilizations grew and developed, mapping techniques became more refined. The ancient Babylonians created clay tablets impressed with symbols for mountains, rivers, and cities. The Egyptians drew maps on papyrus showing the boundaries of land allotments around the River Nile. The ancient Greek polymath, Ptolemy, imposed mathematical rules on his mapmaking. In around AD 150 he published Geographia, a treatise on cartography, with maps showing the coordinates for latitude and longitude. His system revolutionized thinking on geography and had a continued influence on academics well into the Renaissance period.

In Europe during the Middle Ages, maps were mainly produced within monasteries. ,Religion was at the heart of these illuminated and gilded medieval maps. Pilgrimage routes to Jerusalem were documented in detail, if not always accurately. In Arabic countries during the same period, mapmaking was more sophisticated. During the 12th century, the Arab scholar Muhammad al-Idrisi produced a comprehensive atlas entitled The Amusement of Him Who Desires to Traverse the Earth. With the development of improved astronomical instruments, and the setting up of observatories, Arab scholars like al-Idrisi were able to measure the arc of a meridian. This allowed them to suggest an accurate calculation for the Earths circumference and map more precise distances. Muhammad al-Idrisis map was one of the most accurate in the world at the time and its information was still in use centuries later.

From Maps to Cartography

As cultures began to travel farther for trade and colonial exploration, the need grew for more advanced and detailed maps. From around the middle of the 15th centurythe beginning of a period known as the Age of Discoverythere began widespread exploration in Western Europe, and the subsequent mapping of the Americas, Africa, and Eurasia. Portuguese nautical charts developed the use of rhumb lines (the imagined lines, commonly used in maritime navigation, that cross the Earths meridians all at the same angle). The Dutch, with their domination of seafaring and trade, created maps that were not only accurate but so ornamental that they were considered works of fine art. In 1569, the Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator invented a method for presenting a spherical globe as a flat map. Known as the Mercator projection, it is still used today.

Next page