Contents

Guide

Page List

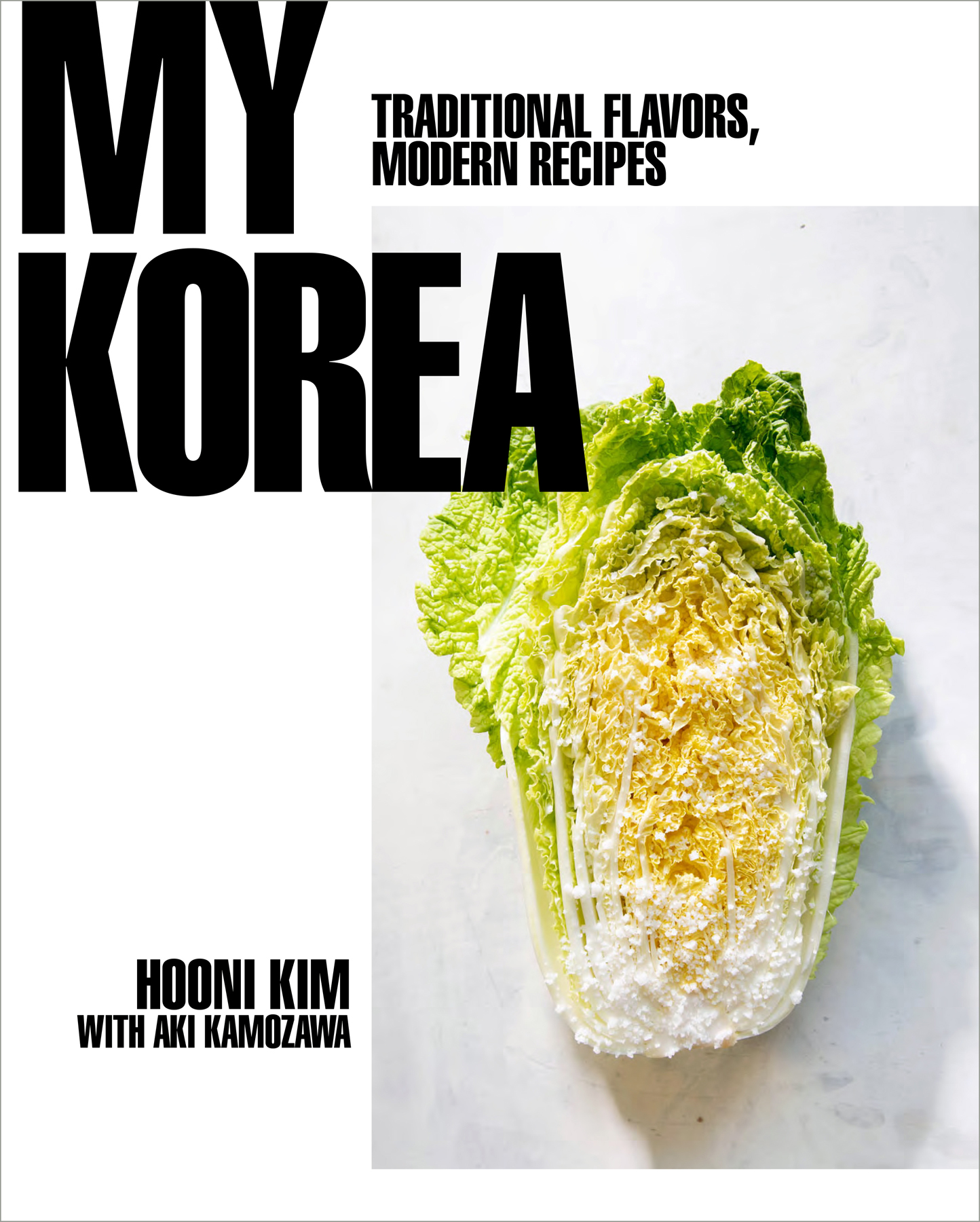

MY KOREA

TRADITIONAL FLAVORS,

MODERN RECIPES

HOONI KIM

WITH AKI KAMOZAWA

Photography by Kristin Teig

To my wife, who shows me every day what it means to be good.

To our son, Sean, who gives us so much joy in life.

And to my mother, whose infinite love gave me the strength to disobey her.

If you are going to follow links, please bookmark your page before linking.

CONTENTS

I experienced what would become my first taste memory when I was four or five years old. I was visiting my maternal grandmother in the city of Busan in South Korea, a bustling metropolis crowded with restaurants and with vendors hawking street food. My cousins took me to a small food cart in one of the endless alleys in the neighborhood. There was a knot of people gathered around it, young and old, jostling for space.

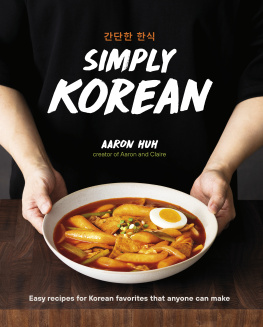

A woman was cooking on an enormous makeshift flat-top grill, and the strong, savory, spicy aroma wafting toward me pulled me forward. She was using a huge wooden spatula to move around small white oblong-shaped pieces of rice cake and thin triangular pieces of fish cake that were smothered in a glistening, bright red gochujang sauce. This was tteokbokki, a popular street food loved by Koreans everywhere.

My cousins paid the woman 10 Korean won (the equivalent of one penny) and I was given a single toothpick and the chance to spear either a piece of rice cake or one of fish cake. I went for the steaming-hot soft, and chewy rice cake. As I took my first bite, the powerful flavors of the gochujang sauce hit me all at once: spicy, tangy, sweet, and salty. The combination of slightly sweet, tender rice cake and rich, vibrant sauce struck the perfect balance. I had never eaten anything like it before and it was almost violently goodthe flavors felt like they were punching away at my palate, in the best ) was the first food to make it on the must-eat list that I later developed for my annual trips to Korea.

My second taste memory was gim (laver, or dried seaweed). Thanks to the popularity of Japanese cuisine, many people in the US are familiar with nori, the laver used to make sushi rolls and hand rolls. More recently, Korean seasoned seaweed snacks made with gim have also become popular in the States. You can see little kids running around in New York City playgrounds and eating these crisp pieces of seaweed, which are considered healthy by their moms and nannies. Even my neighborhood supermarket carries gim snacks.

As addictive as those packaged seaweed snacks can be, their flavor pales in comparison to gim that is toasted and salted at home. When I was a child, I thought gim was the best-tasting banchan (side dish) on the table, and I would tell everyone that the gim was all mine, off limits to my older cousins. There is a delicate crispy texture to gim that is freshly toasted, which puts it on a whole new level.

Its quite easy to prepare gim at home. Lightly brush freshly pressed sesame or perilla oil on the sheets of seaweed and then toast it over an open flame (or simply toast it in a pan). Sprinkle a little salt on top and serve immediately. Once you taste this crackly gim wrapped around warm, freshly made rice, the memory will stay with you forever, as it did for me.

Gim was always my favorite food to eat when I visited my paternal grandmother, who lived on the distant island of So An Do, my late fathers birthplace. So An Do is a tiny island off the southernmost tip of the Korean peninsula, located in South Jeolla Province. All the people on the island are descended from five original families of settlers. It still feels like a small village, and everyone is like family. Even today, when I visit So An Do, villagers will greet me as Jun-Hos son rather than using my name.

When I visited So An Do as a young child, each household not only grew its own vegetables and raised its own livestock, it also dried its own Korean red chili peppers to make gochugaru (red chili flakes) and made its own jangs (Korean fermented bean pastes or sauces). Families prepared their own gim as well, harvesting the seaweed from the ocean that surrounded them. Being in So An Do was like going back in time to a different era, when people were directly connected to the land and the sea. Everything we ate there was precious. Food was not purchased; it was harvested or homemade. Everyone appreciated how much time, effort, and care went into growing, catching, and reaping the food, because they did it themselves. The food was necessary for survival, yes, but it was much more than that. It was truly a labor of love and, as such, invaluable.

But the trip to So An Do was very difficult. Coming from the modern comforts of London, I hated the long, arduous journey. When I was a child, it took three whole days to get there from the UK, where we lived at the time. My mother and I would transfer from plane to plane to bus to taxi to ferry and, eventually, to a rickety twelve-foot-long wooden boat for the thirty-minute boat ride to my late fathers home.

I dreaded the lack of modern bathrooms and air-conditioning. There was only one store on the entire island, and it housed the sole telephone for the community. Nevertheless, I knew the importance of making that trip, year after year. My father, who had passed away when I was two years old, was my grandmothers only child, and I was her sole grandchild. While I dont remember my father, I remember how much my grandmother doted on me. She would hold my hand, crying, while I slept, watching over me all night long and remembering her own son.

As I grew older, I learned to appreciate all the foods that So An Do had to offer. At every meal, I enjoyed the homemade kimchi and jangs, just-laid eggs, vegetables from the backyard garden, and seafood caught by my uncles. Every ingredient was so fresh and delicious. As much as Id originally dreaded the long, exhausting trips to So An Do every year, that dread slowly transformed into anticipation of the vivid flavors that I would get to eat once I arrived.

During high school and throughout college, I visited the city of Seoul almost every summer. My list of must-eat Korean foods grew exponentially. Grilled short ribs marinated in soy, yangneom galbi (), which had so much depth of flavor that they screamed for a chilled shot of soju (the traditional Korean liquor made from sweet potatoes) to wash them down. During this time, I fell in love with more than Korean food; I fell in love with the whole experience and culture of Korea itself.

KOREAN FOOD IN THE US

My mom and I moved from London to the United States when I was around nine years old. As a Korean American living in New York, I grew up eating the food of the citys Koreatown. What I found there was a far cry from the luscious ingredients we ate in So An Do and the vibrant street foods I had enjoyed in Busan. However, it did serve as a reminder of the food from Korea, and I would find myself back there again and again. Many of my friends would also frequent Koreatown, and, like me, they constantly complained about the quality of the food. Still, we would inevitably be drawn back to that single block of 32nd Street off Broadway. Looking back, I realize that the main draw of Koreatown was the atmosphere and the sense of belonging I felt there. The hustle and bustle, the loud voices speaking in Korean, the throngs of people there on a Saturday night, and the smell of kimchi and doenjang all transported me back to my visits to Korea. Surrounded as I was by people who looked like me, it was easy to forget for a moment that I was a minority.